About Studies on the DDR

The German Democratic Republic (DDR) was a socialist state founded in East Germany in 1949 as a democratic, antifascist reaction to the Second World War and the subsequent restoration of monopoly capitalism in West Germany. The DDR represented a new Germany, one in which the land was redistributed, the means of production socialised, and the agricultural system collectivised. It established an egalitarian education, healthcare, and social system and guaranteed equal rights between men and women. It cultivated friendly and close-knit economic relationships with other socialist states and exercised political and material solidarity with countries and movements fighting for their independence in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

The DDR’s declared objective was to establish a just society based on the principles of equality. With public ownership of the means of production as its foundation, the country developed into a powerful and efficient industrial state that used its economic surplus for the benefit of its citizens and guaranteed them a life of social security. Ultimately, the DDR was successful in realising its main socio-political goal: to satisfy its people’s growing material and cultural needs.

Why bother re-examining the DDR’s achievements, principles, and structures thirty years after its downfall? What can we learn from its alternative economic practices in today’s world, where the triumph of capitalism has exacerbated the problems of inequality and poverty and has resulted in more frequent crises? What did socialist democracy really look like? What contradictions arose during the everyday application of a planned economy? What lessons can we draw from the DDR’s ultimate demise?

With this series, Studies on the DDR, the Internationale Forschungsstelle DDR (International Research Centre DDR) together with Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research seek to encourage a new engagement with the history and principles of the DDR. It is our goal to re-evaluate the legacy and experiences of this project of socialist construction. We use the German acronym DDR, or Deutsche Demokratische Republik, (English: GDR) specifically because it often represents a positive point of reference in many parts of the world and especially for countries in the Global South.

This educational series on the agenda and realities of the DDR explores aspects of everyday life, provides facts about the country’s social achievements, and examines the political and economic foundations of this socialist state. By reflecting on the lived experiences of daily life, which are generally left out of the dominant narrative due to the crushing victory of capitalism and the dominance of the market economy, we seek to make a useful contribution to the debates currently taking place within progressive movements. After all, millions of people around the world are still fighting for advancements that were once a given in the socialist system but were lost with its downfall.

In 1990, after the reunification of Germany, the DDR’s economy was dismantled. It was treated as a shock therapy prototype for the austerity measures that were soon imposed on other countries—and not just the former socialist states. At the same time, the DDR was politically, judicially, and morally delegitimised. The publications in this series are a rejection of the narrative propagated by enemies of socialism, both new and old, that the demise of the DDR proves the inevitable failure of socialist policy and economy. By depicting the realities of life in the DDR and by affirming the experiences of DDR citizens, we hope to remind the reader that alternatives to capitalism did and do exist.

This second publication in Studies on the DDR explores the construction and expansion of the DDR’s health care system in the decades following the Second World War. In the context of limited economic resources and fierce competition with capitalist West Germany, the DDR was able to develop a pioneering approach to medicine that placed people over profits and emphasised the importance of social responsibilities in preventing disease. The insights gained from this historical experience of building an effective, universally accessible health care system can serve as a frame of reference for those struggling towards a society organised for and by working people.

1. Health Care in a Sick System

The manner in which a society approaches issues of health reveals much about its general character. The priority given to people’s health, the degree to which individuals are protected and treated equally, and the extent to which health care is geared towards people’s real needs paints a picture of the existing social and political conditions.

Health policy cannot, however, be reduced to the system of medical care alone. It is inseparable from working conditions, nutrition, housing, and education; the character of social relationships; leisure and cultural behaviour; and a number of other factors that form the basis upon which people’s physical and mental health develop. The interrelationship between these elements was already being discussed in Germany during the early development of capitalism. An example of this was the work of the German physician Rudolf Virchow (1821—1902), the founder of modern pathology and a pioneer of what was then referred to as ‘social hygiene’ (Sozialhygiene). This field, now associated with the terms social medicine or public health, investigates the interaction between people’s health and their social conditions. Friedrich Engels, too, provided evidence of this connection in his early work on the condition of the working class in England.

‘All conceivable evils are heaped upon the heads of the poor. If the population of great cities is too dense in general, it is they in particular who are packed into the least space. […] They are given damp dwellings, cellar dens that are not waterproof from below, or garrets that leak from above. Their houses are so built that the clammy air cannot escape. They are supplied bad, tattered, or rotten clothing, adulterated and indigestible food. […] And, if they surmount all this, they fall victim to want of work in a crisis when all the little is taken from them that had hitherto been vouchsafed them.

How is it possible, under such conditions, for the lower class to be healthy and long lived? What else can be expected than excessive mortality, an unbroken series of epidemics, a progressive deterioration in the physique of the working population?’

— Friedrich Engels, one of the founders of scientific socialism, 1845

Under capitalism, health protections must be fought for in a constant struggle against economic interests. Public health policies are primarily determined by the private sector and are increasingly being reshaped by market forces. The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically revealed the serious deficiencies and unsolved challenges of health care systems today. Many states lack clear, scientifically grounded decision-making structures. Solidarity-driven cooperation within and between states is blocked above all by private economic interests. Deaths are shamelessly weighed against economic losses by political and business leaders. Throughout the world, the living and working conditions of the lowest earners make them the most vulnerable to the pandemic. In many cases, they are denied access to vaccines and medicines. The protection of private patent rights is prioritised over comprehensive care for the people. The populations of the Global South are left almost entirely empty-handed.

The overall efficacy of health care systems in the Global North is touted as an indication of their superiority, yet their potential is not fully exploited, nor is their efficacy due solely to economic strength or positive medical traditions. Instead, it is the decades-long struggle of trade unions and other democratic forces that has established minimum standards and basic care. The same forces have thereafter been compelled to defend these gains from the constant pressures of the private sector. Further, the health care systems of wealthier states are bolstered by medical personnel who have been lured away from economically weaker countries. This—coupled with the continued exploitation of the Global South—further exacerbates unequal development between the North and South. Today, the private capitalist sector is consolidating its grip on health care systems, particularly in Western economies, leading health and illness to become increasingly commodified and subordinated to profit-driven motives.

‘Health care, instead of being an accountable system, has grown into a hodgepodge of corporate fiefdoms whose central aim is to maximise profitability for venture capital investors. A profit-oriented health care system requires the physician to act as a kind of gatekeeper, deciding whether to grant or deny health care. A profit-oriented health care system is an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms. As soon as care serves profit, it is no longer true care’.

— Professor Bernard Lown (1921—2021), an American cardiologist and a co-founder of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW)

Since 1991, the proportion of private hospitals and beds in Germany has increased tremendously, continuing a trend of the increasing commercialisation of inpatient care which began in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, commonly referred to as West Germany) in the mid-1980s. This development gained additional momentum in 2003 with the introduction of the U.S.-inspired billing system based on diagnosis-related groups. Under this system, hospital cases are classified into different groups to identify the ‘products’ that patients receive and to determine payment. As such, decisions regarding the treatment and length of hospital stays are increasingly made on the basis of what can be billed profitably rather than on the basis of medical criteria. The quality of health care is thus being eroded, as treatment becomes ever more dependent on patient income and public health services are slashed.

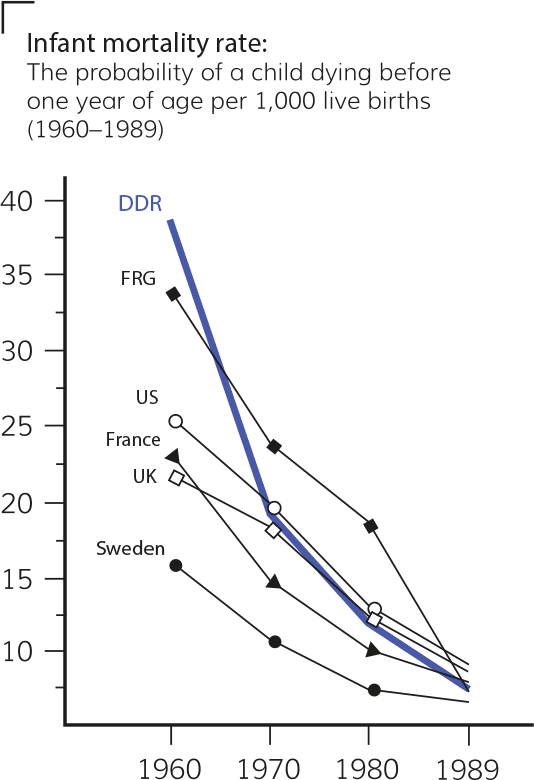

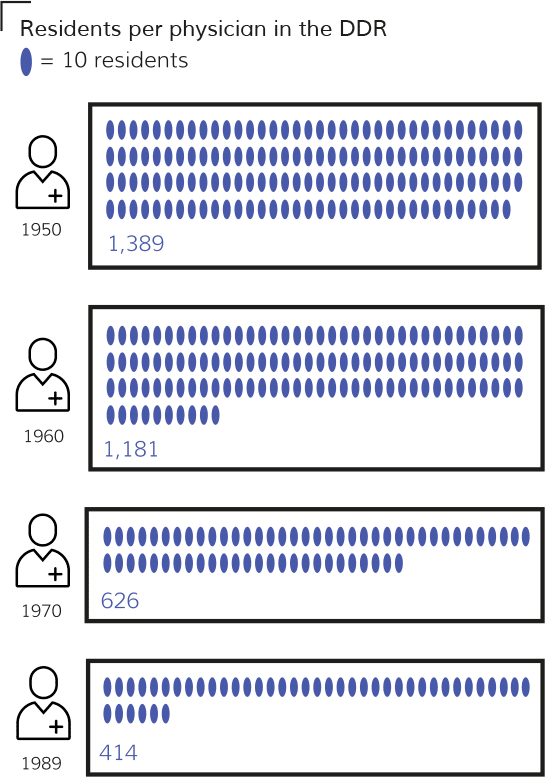

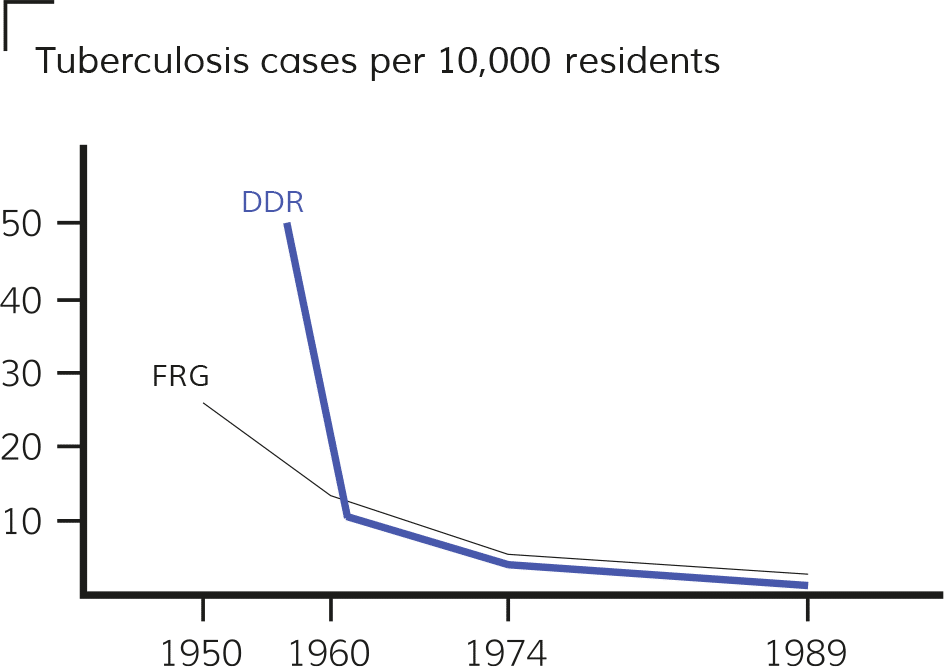

The antagonism between private-sector interests and comprehensive health care for all members of society had already been recognised in the early days of the German Democratic Republic (commonly referred to as East Germany). Throughout its 40-year existence, the DDR was able to construct and advance a fundamentally different health care system. From an initial position of great economic disadvantage, the DDR came to be ranked among the 20 largest industrialised countries in terms of economic production and living standards by the end of the 1980s. The well-being of its 16 million inhabitants was reflected by favourable, even leading values according to certain World Health Organisation measures such as the physician-to-population ratio, infant mortality, and the reduction of tuberculosis. This was despite the suboptimal structural condition of many health facilities, the scarcity of medical supplies, and restrictions on the import of medicine and technology—much of which was the result of economic sanctions imposed by the West.

Bundesrepublik Deutschland [Federal Republic of Germany]. Gesundheitsbericht für Deutschland [Germany’s Health Report]. Bonn: Statistisches Bundesamt, 1998; Deutsche Demokratische Republik [German Democratic Republic]. Statistische Jahrbücher der DDR [Statistical Yearbooks of the DDR]. Berlin: Staatsverlag der DDR, 1956—1991; World Bank Open Data. ‘Mortality rate, infant (per 1,000 live births)’. The World Bank Group. Accessed 1 November 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN?end=2019&locations=GB-U.S.-SE-FR&start=1960&view=chart.

This study assesses the DDR’s health care system and traces several of its central elements, examining the significance of the DDR’s socialist character in the construction of a health care system based primarily on preventive principles. This endeavour did not proceed without its difficulties and contradictions, and the insights gained from this process of building an effective, accessible health care system within the context of limited economic resources can serve as a reference for struggles worldwide. The title, Socialism Is the Best Prophylaxis, pays tribute to a well-known quote of Maxim Zetkin (1883—1965), a physician, politician, and son of the international women’s rights activist and communist Clara Zetkin (1857—1933), that became a slogan in the DDR. In line with the focus of the DDR’s health care system, this slogan refers to the medical approach known as prophylaxis that seeks to prevent disease before it manifests.

Deutsche Demokratische Republik [German Democratic Republic]. Statistische Jahrbücher der DDR [The DDR’s Statistical Yearbooks]. Berlin: Staatsverlag der DDR, 1956—1991.

2. Historical Conditions in the Years Preceding the DDR

Devastating social and health conditions for the urban proletariat arose against the background of industrialisation in the German Empire (1871—1918). After years of campaigning, revolutionary social democracy succeeded in introducing social health insurance in 1883. While then German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck is remembered as the founding father of state-organised social insurance, it was in fact the struggles of the working class that demanded and won concessions from the government. Bismarck never made a secret of the fact that he sought to push back the political influence of the socialist labour movement. During a session of the Reichstag, he remarked, ‘Without social democracy and without the fear that it generates in a great many people, we would not have made the modest social reforms that we had to grant today’. The introduction of this health insurance system helped to partially cover the cost of treatment, but inadequacies remained as working conditions had not improved and the workers had to pay two-thirds of the premiums. As a result, self-organised health care organisations such as the Workers’ Samaritan Federation (ASB) and the Proletarian Health Service (PGD) emerged, complementing the work of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) respectively during the Weimar Republic. These organisations emphatically demanded the further expansion of public health care.

Image 11. The Proletarian Health Service (PGD) was a self-organised health service that operated from 1921 to 1926. It was explicitly political and continued the tradition of public health by, for instance, supporting the nutrition of schoolchildren and the labour struggles to maintain the eight-hour day, especially in the mining industry and chemical factories. It further advocated for the socialisation of health care and organised concrete, practical assistance by providing health care training and education, accident prevention, and first aid. The PGD also worked closely with the workers’ sports movement to promote fitness.

After German fascism came to power in 1933, the Nazis began misusing medicine to enforce their racist and anti-Semitic ideology against people whom they alleged were inferior, committing crimes against humanity on an unprecedented scale. Following the unconditional defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, a catastrophic health crisis hit the German population. The prevalence of epidemics, diseases, and injuries revealed how wars continue to produce many casualties long after the end of military combat. Hospitals, sanatoriums, and the entire health care system had been destroyed in what then became the Soviet Occupation Zone (SOZ). The supply of medicines collapsed, and epidemics spread uncontrollably, intensified by a large influx of refugees and resettled people arriving from Eastern Europe. Deaths from tuberculosis in this period were twice as high as they had been prior to the war. Typhus, cholera, dysentery, venereal infections, and childhood diseases ravaged the population. The number of doctors halved compared to pre-war levels, and the training of new physicians was interrupted by the closure of universities.

From the defeat of the Nazi regime in 1945 to the founding of the DDR in 1949, the health policies of the SOZ were shaped based on 30 orders issued by the Soviet Military Administration (SMAD), which governed the SOZ from the end of the Second World War until the DDR was established in 1949. The policies were then implemented by the German Economic Commission (the central German administrative body in the SOZ) along with the newly created Central Administration for Health Care and the five regional governments in Eastern Germany. An immediate question confronting the SMAD was how to deal with the doctors and other health professionals who had supported the fascist system. Roughly 45 per cent of physicians had been Nazi Party members, many of them involved in euthanasia and the other atrocities that took place in concentration camps. Many of these individuals fled the SOZ, knowing that they would be treated more leniently in the West. The doctors who stayed posed a politically and morally difficult dilemma: enacting a blanket dismissal of health professionals—as had been carried out among judges and teachers for good reason—was out of the question, if only because of the health crisis facing the country. As a result, doctors who had not been found guilty of any crimes were allowed to continue their work, and many of them later made themselves fully available to the new health system.

Examples of Soviet Military Administration health policy orders:

- 1945: Establishing the Central Health Administration and the Health Offices (Order No. 17).

- 1946: Repealing the racist laws and other Nazi legal provisions (No. 6) and passing an order to combat tuberculosis (No. 297).

- 1947: Introducing a uniform system of social insurance (No. 28); establishing a workplace health system (No. 234); and ordering the establishment of outpatient centres and polyclinics (No. 272).

- Other orders were concerned with controlling individual infectious diseases and establishing medical and scientific institutions.

Many of the doctors and health workers who were entrusted with administrative positions in the SOZ’s general administration were those who had been engaged in resistance or had emigrated or been imprisoned under the Nazi regime. Their immediate tasks were dictated by the decisions of the Allied powers in the Potsdam Agreement of 1945 and the newly legalised political parties in the SOZ. The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) formed in 1946, unifying the two working class parties—the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD)—into a single party in the SOZ and recognised the need for new health structures, especially in outpatient care. When drafting social and health policy programmes for a new, democratic Germany, the authorities in the SOZ drew on the progressive demands and experiences of the Weimar Republic period.

‘Since the full development of the health service will only be guaranteed in a socialist society, there is nevertheless a way for democratic Germany as well. […] This is the nationalisation of the health service. Only in this way can physicians, enjoying economically secure positions as well as resources guaranteed by the state, devote themselves entirely to their duties. Only in this way can the achievements of medical science be made available to the entire population. […] The preservation of the health and the productive capacity of working people is one of the nation’s most important tasks and a prerequisite for reconstruction. […] Hence, health protection must be made a matter for the state and thus for the people as a whole. The aim must be one of securing for everyone the protection of his or her health as the basis of vitality and physical fitness’.

— Health policy guidelines of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), March 1947

The task was now to establish a functioning health care system. This required nationalising health care institutions and guaranteeing the right to health care. Free medical treatment was provided through a universal health care system, and the protection of health was understood as a task for all sectors of society. Separating people’s medical needs from the private interests of capital was a decisive, central idea in providing health care for all; it was recognised that business considerations, particularly regarding freelance doctors working in private practices, ran counter to the progressive development of medicine. This observation had already been put forth by the League of Nations, an international association of states founded after the First World War and the forerunner of the United Nations.

The DDR’s emerging health care system was shaped by the experiences of the Soviet Union and its health system, the architects of which had themselves been inspired by the policy positions of the German Left during the Weimar period (1918—33). After the 1917 Russian Revolution and the Civil War (1917—22), the young Soviet Union became the first state in world history to build a health care system that guaranteed free, universal health care to the entire population, enshrining the right to free medical care in the Soviet Constitution of 1936 as one of the fundamental rights of the Soviet people. Under the model introduced by Nikolai Semashko (the People’s Commissar for Health from 1918—30), medical facilities and services were completely state funded and centrally managed, and a multilevel system of hospitals, specialty clinics, and sanatoria operated at the national, regional, city, and district levels. While aspects of the Soviet model influenced the transformation of the health care system in the SOZ, it was not simply replicated. Some of the ways in which the DDR’s system differed, for example, were the degree of central organisation and the fact that it was not financed solely by the state.

3. The DDR’s Comprehensive Approach to Health Care

‘Health policy in the DDR was understood as a totality of ideological, cultural, economic, social, and medical measures conceived of and practiced with varying intensity and quality within the public sphere. The aim was to help shape and optimise the environmental conditions of peoples’ lives in a way that both protects and fosters their health. Patients were to be treated and cared for using the knowledge and experience of modern medicine. Life was to be steadily and progressively extended’.

— Ludwig Mecklinger, the DDR’s minister of health from 1971 to 1989

The creation of socialist property relations was a crucial precondition for the DDR’s preventive approach to health care. Health-related matters such as working conditions, housing, nutrition, and education could therefore be managed by the state and its democratic decision-making structures. The comprehensive planning of publicly owned institutions made it possible to investigate and tackle everyday health risks. In this endeavour, the DDR built upon the traditions of social medicine, which approached health from a socio-political perspective and focused on the interaction between people’s welfare and their overall living and working conditions. In particular, the focus on preventive care in the workplace and for children, along with a modern concept of outpatient care, demonstrated the integrated and holistic character of the DDR’s health policies.

Image 22. A district health inspector measures sound frequencies in a residential area in order to develop methods for reducing noise pollution. The medical fields of social, occupational, and communal health were responsible for monitoring and safeguarding the health standards of the population’s working and living conditions.

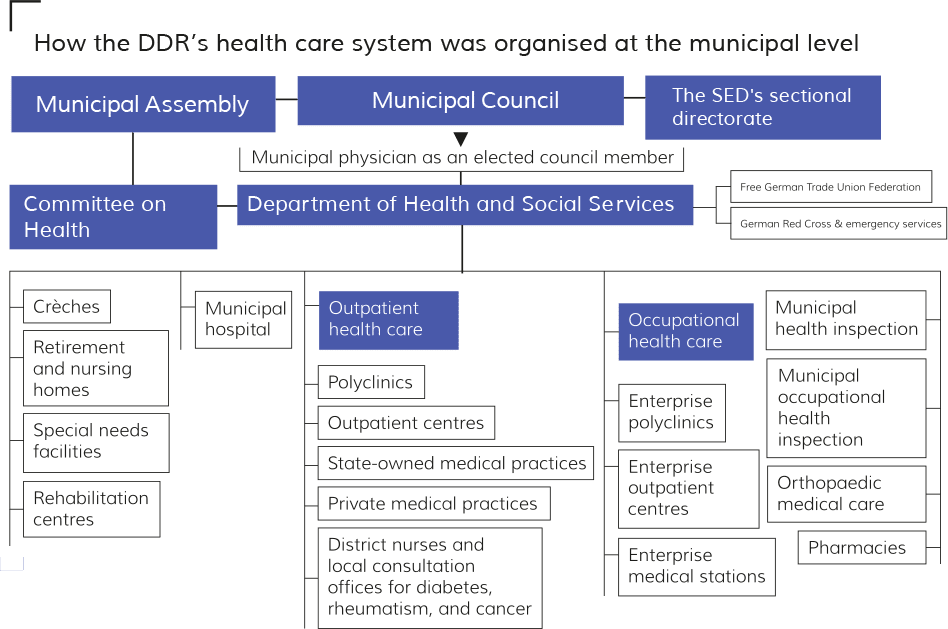

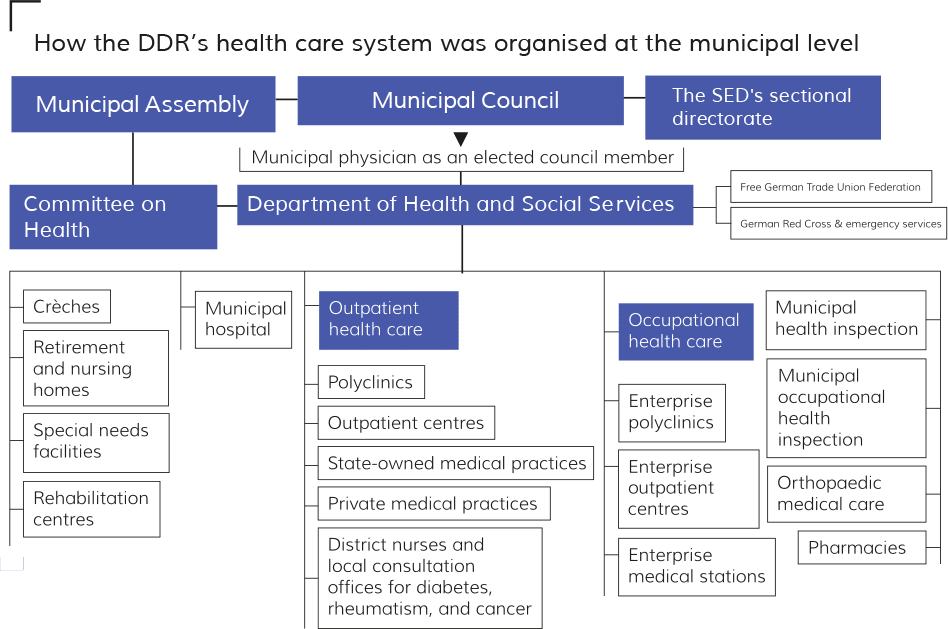

By organising health care institutions as state-owned entities, the DDR overcame the separation found in many capitalist countries today between publicly funded health services and the large, privately organised sector of outpatient and hospital care. The elimination of private forms of ownership enabled the integration of preventive, therapeutic, and aftercare measures that yielded better results for patients. Furthermore, the country’s numerous and diverse medical institutions—from hospitals and clinics to pharmacies and research centres—could now cooperate with one another as part of a unified network led by the Ministry of Health.

How the DDR’s health care system was organised at the national level. Source: Niemann, Heinrich (former specialist in social medicine in the DDR and district councillor for health in Marzahn-Hellersdorf, Berlin). In discussion with the authors. 2 June 2021. IF DDR office, Berlin.

The hospital network in the DDR was steadily expanded to improve accessibility for citizens throughout the country. The tiered system, made up of the communal, municipal, and regional administrative divisions, sought to provide basic care in municipal hospitals, while specialised treatment would be administered in regional hospitals or national institutions and universities. Prior to the Second World War, churches played a significant role in maintaining and operating hospitals throughout Germany. Rather than dismantling these structures, the DDR worked with the clergy to ensure that emergency health care would be available in all areas of the country. Thus, of the 539 hospitals in East Germany in 1989, 75 remained under the jurisdiction of churches, though they too were integrated into the state’s planning system.

The DDR also sought to overcome the historically uneven distribution of doctors across rural and urban areas. After graduation, every physician received both their licence to practice and secure paid employment and was required to work for several years in an area where doctors were particularly scarce based on a commitment made at the beginning of their studies. This policy, referred to as the steering of graduates (Absolventenlenkung), was the DDR’s solution to a serious problem that still besets many countries today.

‘There came a point when we were told: “ You have committed yourself to serve where society needs you”. Many who studied in Berlin then tried everything possible to stay in Berlin to avoid going to Cottbus or Bitterfeld, for example, into the brown coal district, into the dirt. I said to myself: “Well, these are people who have a right to adequate medical care. They shouldn’t be abandoned there, so I’ll do it”. For me, it was fulfilling a promise that I had made in return for being able to study free of charge. We even received a scholarship that allowed us to study without financial difficulties. Such an obligation does not contradict my understanding of fairness in any way, even today. It was perfectly acceptable to me’.

— Dr. Rüdiger Feltz, a practicing neurosurgeon

To finance its health care system, the DDR introduced a broad social security scheme that covered health, accident, and pension insurance and was managed by the workers themselves through the Free German Trade Union Federation. This integrated, state-organised model replaced the fragmented and profit-oriented insurance systems that still operate in many capitalist countries today. Individuals in the DDR paid up to 10 per cent of their monthly wages to the scheme, though contributions were capped at 60 Marks per month for workers. Enterprises then matched the contributions of their employees, and additional state subsidies covered any shortfalls.

The political weight given to health care in the DDR is also illustrated by the country’s extensive legislation on this issue. The universal right to health care regardless of one’s social situation (which had already been anchored in the DDR’s first constitution in 1949) was enshrined in the two subsequent constitutions of 1968 and 1974. The DDR thereby realised Article 25 of the UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that every human being has ‘the right to a standard of living adequate for health and well-being […] including food, clothing, housing, medical care, and necessary social services and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age, or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control’.

Article 35 of the DDR’s 1968 Constitution:

(1) Every citizen of the German Democratic Republic shall have the right to the protection of his or her health and labour power.

(2) This right shall be guaranteed through the planned improvement of working and living conditions; the fostering of public health; the implementation of comprehensive welfare policies; and the promotion of physical activity, school and popular sports, and tourism.

(3) In the event of illness or accident, the loss of income and the costs of medical care, medicines, and other medical services shall be provided through a social insurance system.

The DDR guaranteed not only basic health-related rights and duties in the sphere of medical care, but also in the spheres of work and education. Equal rights for women as well as health protection for children, youth, and the elderly were also codified. This included internationally commended legislation that decriminalised homosexual acts in 1968 (though they had already been exempt from legal prosecution since the 1950s) and legalised abortion in 1972. Other significant statutes included the introduction of state liability for health damages caused by medical procedures (1987) and the ‘dissent solution’ for organ transplants (1975), which established a presumed consent model for organ donation that required individuals to opt out.

Niemann, Heinrich (former specialist in social medicine in the DDR and district councillor for health in Marzahn-Hellersdorf, Berlin). In discussion with the authors. 2 June 2021. IF DDR office, Berlin.

The DDR’s health care system was a highly complex sector that was gradually and systematically developed over the course of four decades, employing nearly 600,000 people—roughly 7 per cent of the total workforce—by 1989. In addition to hospitals and outpatient clinics, this sector included medical teaching and research facilities; specialist institutes; emergency services; scientific societies; medical publishers and journals; health education facilities; and, last but not least, an extensive pharmaceutical industry. With thirteen enterprises, three research institutes, and approximately 15,000 employees, the Kombinat GERMED—meaning ‘combine’, a sort of socialist corporation—produced some 1,300 different medical products, meeting 80—90 per cent of the DDR’s pharmaceutical needs while also exporting medical products to the Soviet Union and other socialist countries. The domestic demand for medicines was communicated to suppliers not through market forces but through the calculations of district pharmacists. Pharmacists, like physicians, were free from profit-oriented considerations in their work, and medicines were provided free of charge to all citizens. Close collaboration between pharmacists and physicians enabled them to tailor patient care and adjust medications if supply shortages occurred.

Image 33. In 1950, there were 1,694 pharmacies in the DDR, of which 1,266 were privately owned. By 1989, there were 24 private pharmacies and 2,002 public pharmacies managed by the Ministry of Health. Each of the DDR’s 15 regions was overseen by a head doctor and head pharmacist. On the district level, local pharmacists were responsible for monitoring the distribution of medicine according to unified standards.

4. Contradictions and Challenges

The development of the DDR’s health care system was not free from conflicts and challenges. Contradictions between the country’s health care objectives and its economic capacity meant that stated goals and aspirations could not always be achieved. Health policies reflected both the economic difficulties facing the country and shifts in political priorities. For example, when the Unity of Economic and Social Policy was introduced in 1971 to increase access to consumer goods and services, the health sector initially benefited from extra funding. Yet this shift in investment policy away from the industrial sector created imbalances in the planned economy that were ultimately felt in the health sector, too. This was apparent, for instance, in the wear and tear on hospitals and the scarcity of certain medical supplies and equipment, which made health workers’ day to day tasks more difficult. In its final years, the DDR was no longer able to import modern medical technology developed in Western industrialised countries to the extent needed, in part due to the embargo imposed by the West. While innovative diagnostic and therapeutic methods enabled the DDR to make progress against certain diseases that had previously proven difficult or impossible to treat by conventional methods, these efforts were often hampered by a lack of equipment.

In the 1980s, bottlenecks in the supply of materials as well as differing views on how to tackle urgent health issues led to intensified policy debates. The preventive approach to care and the conviction that all social sectors had a role to play in public health remained decisive underpinnings of government policies. Yet, disputes arose around the question of which disease-causing conditions could and should be prioritised. For instance, at times there was an emphasis placed on measures that sought to change unhealthy behaviours in order to combat problems such as obesity, alcohol abuse, and an increase in smoking amongst the youth. This approach of focusing on individual behaviours that contribute to health issues was criticised by social medicine specialists, who instead focused on improving the population’s overall living and working conditions. Such debates reveal that everyday difficulties and strategic questions were open to political discussion, which often took place in bimonthly regional physicians’ meetings and biannual municipal physicians’ conferences, among other venues.

The West’s hostility towards the DDR affected the development of its health system in many ways, exerting an ideological, political, and economic influence on the DDR’s health workers and structures. This had a particularly notable impact on the country’s access to medical and technical material as well as international research initiatives. In addition, West Germany actively poached East German doctors by encouraging them to migrate westward. Physicians who had enjoyed cost-free education and training in the DDR were attracted to the West by better pay or by their reluctance to participate in the social transformations underway in the East. This dynamic impacted the DDR from the outset: the exodus of doctors following the Second World War was so massive that it would have required at least five additional graduating classes of all DDR medical schools to compensate for the loss. This was similar to the situation in Cuba, where—apart from doctors like Che Guevara who committed themselves to the revolution—many doctors left the island for the United States after 1959. This phenomenon of ‘brain drain’—in which physicians and other highly educated or skilled professionals emigrate from those countries where they are most needed—and its consequences for the Global South are generally brushed off or sold as a positive aspect of globalisation.

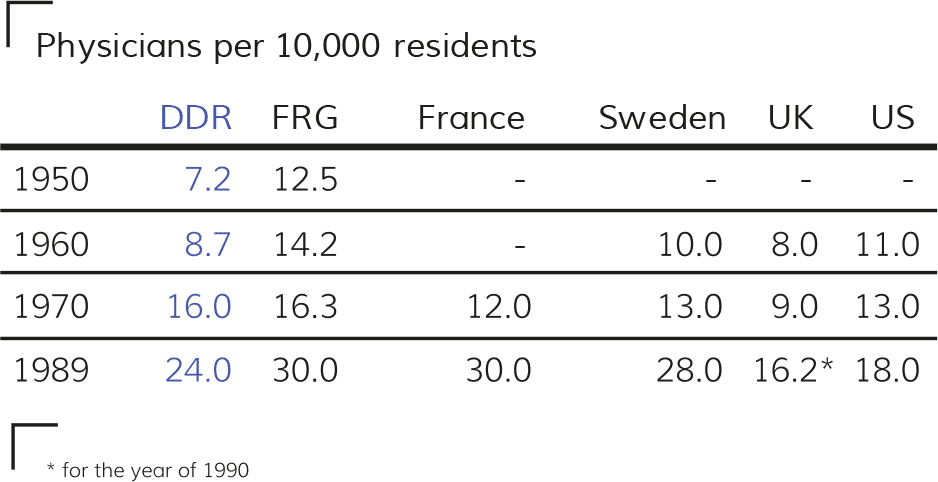

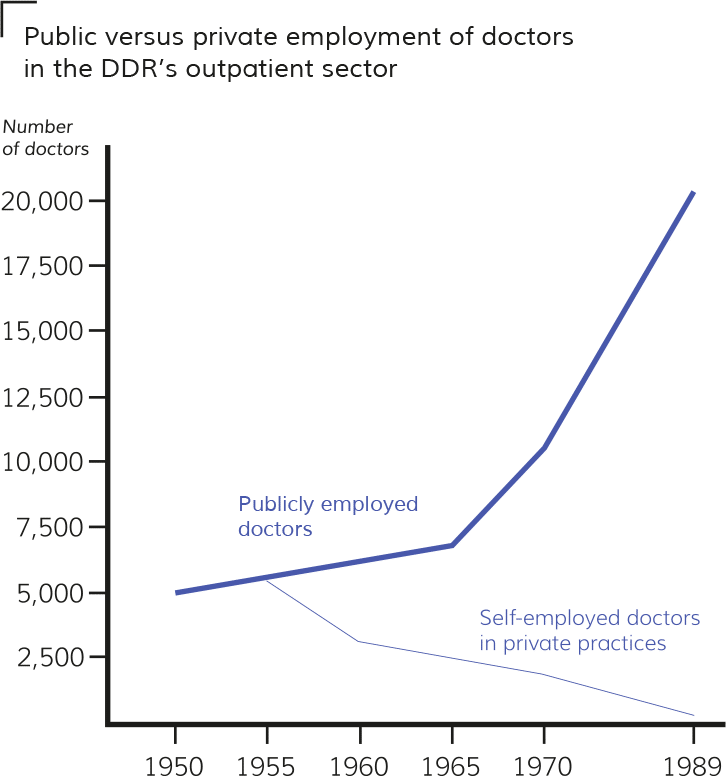

Until the border between East and West Germany was closed in 1961, the DDR was also pursuing its pioneering health programme in ‘competition’ with the FRG, which preserved the private practice model and deliberately used high salaries and privileges to incentivise well-trained doctors to leave East Germany. The DDR was thus faced with the same difficulty that confronted the Bolsheviks after the October Revolution: how could the specialised professionals and intelligentsia, who had been privileged under capitalism, be won over to the construction of socialism? Given the high levels of emigration, the SED decided to make concessions to the medical intelligentsia in the late 1950s, utilising material incentives to encourage doctors to work and live in the DDR. Despite these challenges, further shifts away from private practices to public employment prevailed in the following years. Although several thousand doctors left the DDR before the Wall was built in 1961, by 1988 the number of physicians in the country (around 41,000) had more than tripled since 1949, putting the DDR’s physician-to-population ratio on par with the other industrialised states in Europe.

Deutsche Demokratische Republik [German Democratic Republic]. Statistische Jahrbücher der DDR [Statistical Yearbooks of the DDR]. Berlin: Staatsverlag der DDR, 1956—1991; Rahlf, Thomas, ed. Deutschland in Daten [Germany in Data]. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2015; World Bank Open Data. ‘Physicians (per 1,000 people)’. The World Bank Group. Accessed 1 November 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.MED.PHYS.ZS?locations=U.S.-FR-SE-GB.

5. The Polyclinic: A Modern Approach to Outpatient Care

5.1 From Private Practice to Polyclinics

Under the capitalist model of health care, outpatient care is commonly provided by independent doctors in individual private practices that are scattered throughout cities and towns. Progressive medical traditions have, however, long criticised this model as having two significant limitations. Firstly, self-employed doctors are economically dependent on sick patients seeking out treatment. That is, they are financially incentivised not to prevent disease but to treat symptoms after they manifest. Secondly, the rapid advance of science has greatly improved medical diagnostics and treatment capabilities, but these new methods require access to the latest technology and expertise. Since individual practices cannot house the diverse equipment and staff demanded by modern medicine, patients are referred to separate specialists or diagnostic centres, often creating inefficiencies and discrepancies in diagnoses. In the DDR, polyclinics were developed to overcome these issues in outpatient care.

As the name implies, polyclinics were facilities in which multiple medical specialties collaborated under one roof to prevent and treat a wide variety of diseases. More specifically, polyclinics were defined as publicly owned outpatient facilities containing at least the following six specialist departments: internal medicine, oral medicine, gynaecology, surgery, paediatrics, and general medicine. Many polyclinics also housed clinical diagnostic laboratories, physiotherapy departments, and medical imaging facilities. In addition, polyclinics embodied the conviction that, to be effective, outpatient medical care had to be severed from personal economic considerations. Physicians and staff working in polyclinics were publicly employed and thus freed from their traditional economic dependencies on the sick. With a secured position and a reasonable income, doctors could focus first and foremost on preventive care.

It was again the transition away from private ownership that enabled this fundamental reorientation of the outpatient sector, which plays an important if not decisive role in the capacity of a health care system to serve the entire population. Effective outpatient care ensures that the medical help people need is directly and rapidly available where they live, from prevention and therapy to aftercare and rehabilitation, which helps to minimise inpatient stays in hospitals and ideally prevents illness in the first place. The clustering of medical departments, technology, and laboratories under one roof helped to overcome bureaucratic and financial obstacles that plagued private practices. At the same time, this design facilitated more effective collaboration between medical professionals from different fields.

‘Does not […] the real freedom of the physician consist in the fact that they are given the means to secure the health of each individual citizen without limitation? By building up the state health system, physicians are no longer economically interested in people falling ill; they can instead genuinely act as the guardians and preservers of health’.

—Speech at the National Health Conference in Weimar, 1960

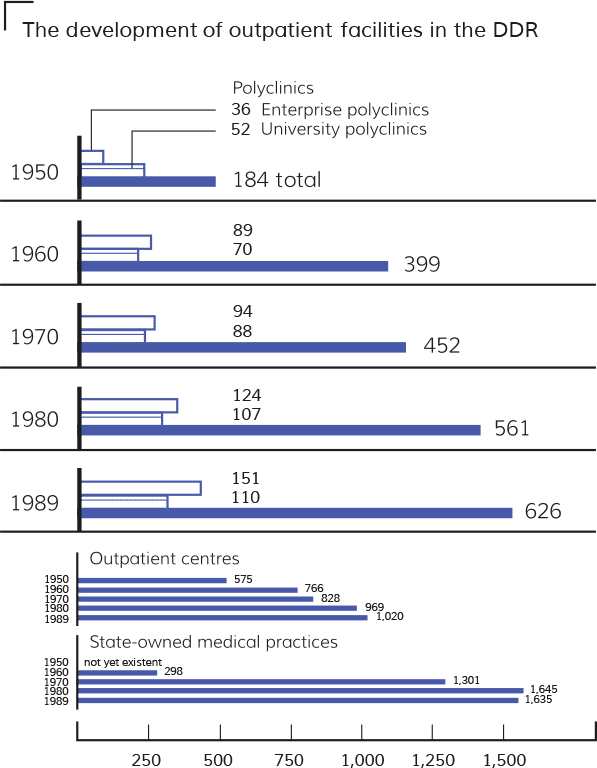

Smaller institutions embodying the same approach as the polyclinic were called outpatient centres (Ambulatorien) and typically housed at least three different departments: general medicine, internal medicine, and paediatrics. More than a third of the outpatient facilities were affiliated with hospitals and university clinics to promote medical collaboration. Consultation centres and state-owned individual practices operated in more remote locations but were organisationally linked to polyclinics for support.

Transforming the outpatient sector presented unique challenges both in terms of infrastructural requirements and the new roles of health care workers, unlike the hospital system, which had a longer history of public ownership. There was, for instance, considerable scepticism and even resistance to the idea of polyclinics among physicians. The radical idea of publicly employing medical specialists to work together under one roof sharply contrasted with the deeply rooted self-perception of the ‘freelance’ doctor who works for him or herself.

Several forerunners of large medical complexes served as inspiration to the DDR’s polyclinic system, such as the House of Health in Berlin, constructed in 1923 during the Weimar Republic. Architects of the DDR’s Bauakademie(Academy of Civil Engineering) began to develop and refine similar projects in the 1950s under the leadership of then President Kurt Liebknecht. When the DDR’s immense housing construction programme was announced in the early 1970s, it specified that polyclinics or outpatient centres were to be incorporated into the new estates. Larger polyclinics were built in Berlin as well as in other big cities, each staffed with upwards of 50 doctors.

Conservative physicians’ associations had already begun systematically opposing calls to establish polyclinics during the Weimar era, and they resumed this offensive after the end of the war in 1945. The DDR’s policymakers sought to demonstrate the advantages of the new model by expanding the technical capabilities and laboratories in polyclinics. This was a gradual process; for many years, private practices continued to provide a large portion of outpatient care.

Deutsche Demokratische Republik [German Democratic Republic]. Statistische Jahrbücher der DDR [Statistical Yearbooks of the DDR]. Berlin: Staatsverlag der DDR, 1956—1991.

5.2 The Operation of Polyclinics

Physicians and staff working in polyclinics were employed and remunerated by the state, removing personal economic motives from the doctor-patient relationship and the medical decision-making process. In contrast to private practices, polyclinics established unbureaucratic cooperation between individual specialties. Under capitalist health care systems, self-employed outpatient physicians have generally been (and often still are) solely responsible for medical decisions, whereas the collaborative structures in polyclinics made it easier for specialists across different disciplines to discuss complicated cases or, for instance, the prescription of new medications and recommendations for new types of therapy. This interdisciplinary collaboration also provided a framework in which the relationship and communication between preventive, therapeutic, and aftercare measures could be strengthened and brought closer together. Laboratory and medical imaging services could be requested immediately and were usually available within a short time or even during the consultation itself. Polyclinics were also able to house superior medical equipment, mainly because common usage was more cost-effective than individual use in private practices, and a uniform filing system for patient records was maintained to reduce inefficiency and miscommunication between specialists.

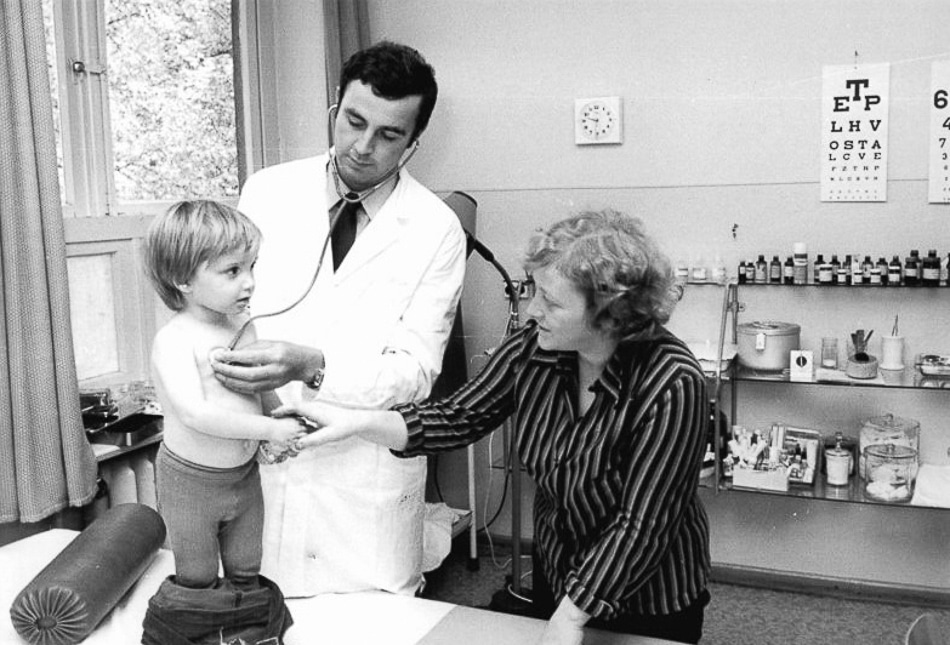

On average, polyclinics staffed 18 to 19 physicians, which allowed them to extend hours of operation and continue to provide care even when individual doctors were sick or on holiday, unlike in private practices. In addition, this allowed physicians to provide more extensive care to their patients, as they could couple their normal consultation hours with on-site visits. Paediatricians, for instance, were able to conduct regular check-ups in childcare centres while other doctors took charge of walk-in consultations in polyclinics.

‘The fact that a doctor always has to worry about how to secure their income and is dependent on sick people coming to them cannot be the solution. Another solution must be found. Namely, to understand doctors as well-paid employees of the state who can conduct their duties independently of their income. That was one of the basic ideas in the DDR. A second was that the modern development of science no longer corresponds to the model of private practice. I need structures where I can access the laboratory, X-ray machines, and specialists. These two basic ideas led to the gradual creation of polyclinics, or outpatient centres. It was a long process, and one that faced resistance’.

—Dr. Heinrich Niemann, a specialist in social medicine and former policymaker

The new model of employment in outpatient care greatly improved the collegial atmosphere in the health sector. Staff were guaranteed fixed working hours, in-house health care, communally organised meals, and joint holiday facilities for themselves and their families. Importantly, physicians, assistants, and nurses were all employed as staff members; they were treated equally in accordance with labour laws and were organised within the same trade union. These measures gradually helped erode professional hierarchies.

Image 44. Dr. Heinrich Niemann remembers: ‘At the beginning of the 1980s, the large Dr. Karl Kollwitz Polyclinic was built in the working-class district of Prenzlauer Berg in Berlin. The doctors who had already been working there in private practices did not go into polyclinics with flying colours. Of course, they knew that the moment they worked in such a large facility, a different mode of operation, a new way of working together would be necessary. […] Yet, this is the only way that a unity can be established between therapeutic, rehabilitative, and preventive measures. Still today, a private practice can only achieve this to a limited extent’.

5.3 An Overview of the Outpatient Sector

Outpatient care was a central component of the DDR’s preventive approach to medicine, and its expansion and success in ensuring that all citizens received medical coverage not only during emergencies but throughout the course of their lives arguably represents the most revolutionary aspect of the country’s health care system. In order to achieve this, a vast network of infrastructure was developed in neighbourhoods, workplaces, childcare centres, and rural locations. Through public ownership and the planned nature of the economy, it became possible to shape living and working conditions around health considerations.

Deutsche Demokratische Republik [German Democratic Republic]. Statistische Jahrbücher der DDR [The DDR’s Statistical Yearbooks]. Berlin: Staatsverlag der DDR, 1956—1991.

Image 55. Community nursing was a highly skilled and valued profession. The nurses were well acquainted with the residents in their region and performed important medical services during house visits such as carrying out examinations, dressing wounds, administering medicines and injections, and arranging for a doctor’s assistance when necessary.

In order to extend preventive care to rural areas and scattered villages, rural outpatient centres were built and staffed with up to three doctors, with the number of these facilities rising from 250 in 1953 to 433 by 1989. In many towns, physicians worked in public medical practices or temporarily staffed field offices to provide residents with consultation hours and home visits, while mobile dental clinics visited remote villages to provide all children with preventive care. In addition, the profession of the community nurse was developed in the early 1950s to alleviate the initial shortage of doctors in the countryside, with the number of community nurses expanding from 3,571 in 1953 to 5,585 by 1989. This extensive rural infrastructure helped to provide less densely populated regions with medical services comparable to what was available in urban areas.

‘There was no separation between care work and social work in community nursing, so it was a completely logical development for the nurses that social services became part of the health sector in 1958. […] In villages where there was no doctor, the community nurse was responsible for everything related to health, social, and hygiene matters. Some became members of the local council, and a few became deputy mayors’.

—Dr. Horst Rocholl, a former municipal physician

The DDR’s revolution in outpatient care went beyond the construction of infrastructure. Comprehensive reform was also carried out in the educational system to break down traditional barriers and hierarchies in the field. This included, among other measures:

- Providing tuition-free education and fixed stipends to cover students’ living costs and ensure that medicine became accessible to the working class and peasantry.

- Implementing socio-political measures such as comprehensive childcare and distance education programmes to make medical professions more accessible to women, who, from the late 1970s onwards, often made up more than 50 per cent of medical students in the country.

- Turning nursing and caretaking into highly qualified and respected professions through intensive academic training programmes.

- Making higher education in medical specialties available to all physicians.

However, after 1990, the FRG’s private practice model was rigorously imposed on East Germany, undoing the DDR’s achievements in the outpatient sector. While many East German professionals were stripped of their credentials after the DDR was incorporated into the FRG, no one dared to seriously question the qualifications of East German health professionals: in cases where they were barred from practicing, the motive was almost always political. Furthermore, the liquidation of the polyclinic system represented ‘the greatest blunder in health policy’ after unification, as Dr. Heinrich Niemann argued before the Health Committee of the German Parliament in 1991—an assessment corroborated by the precarious state of the health system in Germany today. While the FRG made it possible in the late 1990s for outpatient doctors to work as employees rather than freelancers, these clinics are almost exclusively under private ownership and lack a unified structure, and their commercial orientation marks a significant regression from the integrated and publicly funded outpatient facilities of the DDR.

6. Protecting Health in the Workplace

In East Germany, workers’ health was given great importance from the very beginning. In 1947, during the period in which Germany was still occupied by the four Allied powers, the Soviet Military Administration issued Order No. 234, which stipulated that workplaces with more than 200 employees were to set up medical stations, while those with more than 5,000 employees were to establish enterprise polyclinics. Within three years, 36 enterprise polyclinics had been set up, and by 1989, they numbered more than 150. The enterprises themselves were responsible for maintaining the rooms, furnishings, and operating costs of these health facilities while the state health system provided and oversaw the medical staff and equipment. This point represents a decisive contrast to the occupational health care that is offered in some private companies today: in the DDR, the medical professionals overseeing occupational health and safety were employed by the public health system, not the enterprise within which they worked. As such, it was the interests of the workers, not the employers, that guided their medical decisions.

In the DDR’s first constitution in 1949, legal protections for workers’ health were laid out alongside the extensive social insurance system. In the subsequent constitutions in 1968 and 1974, these protections were expanded, and their implementation was overseen by the workers themselves: the Free German Trade Union Federation, present in all enterprises and institutions of the DDR, was tasked with monitoring the enforcement of legal provisions and reporting on their effects. By law, the workplace represented much more than merely a source of income. Enterprises provided the framework in which employees could pursue cultural and intellectual interests alongside recreational activities. Workers’ brigades were encouraged to attend cultural and sporting events, discuss political developments, and visit holiday camps maintained by the enterprises. The DDR’s Labour Code of 1977, for instance, contained clauses to protect and promote both the physical and mental health of employees. This legislation further demonstrates that the inte rests of working people determined the direction of the economy.

The DDR’s Labour Code of 1977

§ 2 (4) Labour law is aimed at improving, in a planned manner, the working and living conditions of employees in the enterprises: specifically, to expand health protection; to enhance labour power; to improve social, health, intellectual and cultural programmes; and to increase the workers’ opportunities for meaningful leisure time and recreation. It guarantees working people material security in the case of illness, disability, and old age.

§ 17 (1) Enterprises as defined by this law are all state-owned establishments and combines as well as socialist cooperatives.

§ 74 (3) The enterprise shall systematically reduce hazardous working conditions and limit the amount of physically difficult and monotonous work.

§ 201 (1) It shall be the duty of the enterprise to ensure the protection of the health and labour power of working people primarily by organising and maintaining safe working conditions that are free from hardship and conducive to health and efficiency.

§ 207 Workers who are to undertake work which is physically demanding or hazardous to health shall be medically examined free of charge before employment and at regular intervals in accordance with legislation.

§ 293 (1) The supervision of occupational health in enterprises shall be conducted by the Free German Trade Union Federation (FDGB) through health and safety inspections.

As with the outpatient sector, the system of occupational health was gradually expanded. By 1989, it covered 7.5 million workers from 21,550 enterprises, or 87.4 per cent of all working people in the DDR. Institutions specifically dedicated to this field—such as polyclinics, outpatient centres, and medical stations operating within enterprises—employed some 19,000 health care professionals. Occupational medicine was also established as a major field of study, with approximately one out of seven outpatient doctors specialising in this field. The Central Institute for Occupational Medicine employed physicians and scientists to research work-related illnesses and develop preventive measures, and the importance that this sector carried in the DDR is evidenced by the fact that the FRG had only half as many occupational health specialists, despite the West German labour force being three times larger than its equivalent in the East.

In certain professions, employees were exposed to hazardous substances and/or particularly arduous physical conditions. Health officials campaigned to reduce the number of such jobs, and enterprises were obliged to report on the measures they were taking to combat harmful conditions. Yet, in certain sectors of the East German economy, such as heavy industry, production processes posed unavoidable threats to workers’ health. By 1989, roughly 1.69 million workers remained exposed to harmful pollutants and stresses such as excessive heat, noise, or vibrations. To minimize the injuries that often resulted from such jobs, the DDR provided targeted care to exposed workers. Of the 7.5 million workers monitored under the occupational health system in 1989, roughly 3.34 million received care that was tailored to the specific conditions in which they worked. For example, regular hearing tests were conducted for those working in construction, while regular lung examinations were conducted for those employed in chemical plants. Alongside these measures, specialist occupational health inspectorates monitored enterprises’ compliance with safety standards and specified limits for harmful substances or work stresses.

Image 66. An occupational health inspection measures noise, temperature, humidity, and lighting conditions. In 1981, a strict obligation was placed on enterprises to report on the conditions of high-risk workplaces and to take measures to reduce these risks. Together, these reports created a solid database through which affected employees could be monitored, protected, and provided with targeted care. The data was also used to exert greater pressure on politicians and enterprises to reduce and, if possible, prevent the harmful side effects of work.

The field of occupational health was particularly important in the context of the FRG’s trade embargo, which caused the DDR to rely heavily on the only energy source readily available in East Germany: brown coal, a lignite-based substance that emits considerable pollution when burned. This economic necessity, alongside shortfalls in technical modernisation in some enterprises, led to special exemptions being permitted regarding harmful exposures in some workplaces. Occupational health and safety thus became a contentious field as officials debated which priorities should be set. Ludwig Mecklinger, the DDR’s minister of health from 1971 to 1989, recognised this dilemma, stating that health policies were inevitably restricted by economic necessities and external factors.

Work-related mental stress was another key issue in the DDR and became the focus of the field of occupational psychology. Here, significant findings were made by the scholar Winfried Hacker, who focused his research on the psychological regulation of labour activity in the context of socialist society, where the greater satisfaction of people’s needs requires increased labour productivity. According to Hacker, work should be designed in such a way that not only maintains workers’ health, but also fosters their psychological development: work that is dull and detached from workers’ lived realities will lead to alienation, whereas a healthy relationship with work must be multi-dimensional and allow workers to develop both themselves and the products of their labour at the same time. To explore these ideas, Hacker and his team of researchers developed methods to identify objective characteristics in the workplace that positively impacted health and psychological development and to measure how they affected subjective perceptions. Although Hacker’s proposals were not implemented on a large scale, his research set the standard in occupational psychology. Hacker’s work differed from the predominant approaches to occupational psychology under capitalism, which prioritise increasing the efficiency of work processes rather than the development of employees’ health and mental state.

Today, the weakening of trade union power and the rise of precarious employment has led to a deterioration in working conditions in most capitalist states. While there have been advances in the production processes themselves, new health burdens are constantly emerging, particularly in connection with digital workplaces, along with agriculture and food industries. As such, the importance of occupational health has only increased, and the experiences of the DDR in this field remain relevant not only from a medical point of view, but also by demonstrating that a fundamentally different approach to health protection in the workplace is possible.

7. Health Care for Mothers and Children

In East Germany, women enjoyed access to first-rate health care, comprehensive childcare, and guaranteed employment. These social achievements meant that by 1989, the employment rate among women had reached 92 per cent. At the same time, from the 1970s, East Germany also had a higher birth rate than the West largely due the continuous expansion of the country’s social and health infrastructure, which enabled women to both pursue employment and raise a healthy family.

The development of this infrastructure was established in the DDR’s legislation, which proved to be consistently more progressive than in the FRG, where patriarchal laws reflected bourgeois familial concepts such as the stay-at-home mother. The DDR’s 1950 Law on Mother and Child Protection and the Rights of Women, for instance, prescribed an extensive expansion of day care and health care facilities for children, explicitly supporting single and working mothers. While in 1956 only 10 per cent of children attended childcare facilities, by 1990 nearly 80 per cent of eligible children attended a crèche (from the age of 0 to 3) and 94 per cent attended kindergartens (from ages of 3 to 6). At the time, these were some of the highest rates of childcare coverage in the world. Women’s committees within trade unions were instrumental in introducing and overseeing new laws to address the need to balance family and work responsibilities. One result, for example, was the establishment of enterprise kindergartens directly connected to the workplace. Through the socialisation of childcare responsibilities, mothers were able to work while also raising children and thus develop economic independence from their partners. This was reflected in East Germany’s divorce rate, which remained significantly higher than in the FRG throughout the DDR’s 40-year existence. This trend was dramatically reversed after 1990, when women’s employment levels fell sharply in the former DDR.

Childcare facilities also played a central role in the health policies of the DDR. These institutions were actively monitored by the Ministry of Health and, in the case of crèches, even placed directly under its responsibility rather than that of the Ministry of Education. This made it possible to create integrated social and health standards to further children’s wellbeing, such as regular paediatric visits to crèches to carry out vaccinations and periodic medical check-ups conducted directly in kindergartens and schools, making health care an integral part of children’s everyday lives. In this way, maintaining good health and detecting potential health issues became a social responsibility that was no longer left to parents alone.

In 1965, the Law on the Unified Socialist Education System made health a central pillar of education and laid out qualification requirements for personnel in crèches, kindergartens, and schools. Child psychology and pedagogy were emphasised in training programmes for crèche personnel. Early childhood development was acutely observed by educators to assess, for instance, children’s adaptation to their familial and social environment. When necessary, crèche personnel arranged for consultations with parents to discuss practical recommendations for everyday care. The Professional Paediatric Association (Medizinischen Fachgesellschaft für Pädiatrie) also convened regular interdisciplinary working groups together with childcare personnel to assess the state of crèches and kindergartens. These groups drew up policy proposals and legislative amendments as well as suggestions for pilot projects.

Image 77. In the DDR, strict norms were developed and enforced to ensure appropriate pedagogical methods, infrastructure, and open spaces at children’s facilities. New housing developments, such as the one in Rostock featured here, were required to include large open spaces for children.

In addition to providing free childcare to all families, the DDR strove to break down cultural taboos and promote the health of women and children, regardless of their circumstances. The 1965 Family Code, for instance, eliminated the discriminatory legal category of ‘children born out of wedlock’ while emphasising the role of both parents in raising a child. The 1972 Law on the Termination of Pregnancy also contributed to women’s self-determination and family planning by introducing free and legal access to contraceptives and abortions within the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. In contrast, the constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany contains a clause criminalising abortion to this day, and, since 1976, women have been required to attend a compulsory counselling session in order to receive an exemption.

Pregnant women in the DDR were guaranteed comprehensive pre- and post-natal consultations to aid and monitor mothers and their children. By 1989, there were more than 850 pregnancy consultation centres throughout the country to guide expectant mothers in medical and social questions. After birth, some 9,700 maternity consultation centres regularly examined infants and assisted the parents in their new roles. Periodic medical examinations then accompanied children all the way to adulthood. Importantly, dental care was also integrated into preventive screenings in kindergartens and schools, again in contrast to most health systems today in which dental health is not publicly guaranteed and is instead left to the financial resources and discretion of parents. Taken together, these structures and policies helped to ensure that family planning and childhood development could unfold independently of economic considerations.

Image 88. A paediatrician carries out an examination in a rural outpatient clinic. In addition to the early detection of health abnormalities, the assessment of a child’s preparedness for school was also part of the preventive screenings. Confidential documentation of all such examinations and findings on health and development accompanied children from birth to graduation.

8. Vaccination Strategies

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the inequalities and inefficiencies of vaccination production and distribution in the capitalist world today. On the one hand, intellectual property rights have been prioritised over public health, leading to vaccination apartheid in which countries in the Global North have amassed enough doses to vaccinate their populations three times over, while most states in the South are prevented from reproducing these same vaccines themselves. If it were not for South-South cooperation headed by countries such as Cuba and China, vaccination rates in poorer states would be far lower than they already are. On the other hand, in a twist of irony, the same states stockpiling vaccines in the Global North struggled to convince a quarter or even a third of their populations of the efficacy and safeness of immunisation against COVID-19.

As in many other socialist states, the DDR was able to achieve particularly high vaccination rates during its four decades of existence. A clear example of this was the campaign against the polio virus. In 1961, while West Germany was still registering over 4,600 cases of polio, East Germany had reduced its number of cases to less than five. The DDR made use of an oral vaccine produced in the Soviet Union and subsequently offered 3 million doses to the FRG, but the latter declined. While East Germany recorded its last polio case in 1962, cases continued to be recorded in West Germany until the end of the 1980s.

Image 99. Vaccinations were a part of the regular medical screenings that accompanied children from birth to adulthood. Health care was guaranteed in crèches, kindergartens, schools, and holiday camps, right through to apprenticeships and university studies. This photograph documents the administering of a new polio oral vaccine in the form of drops.

The differences in the speed and effectiveness with which the two German states tackled polio stem from two fundamentally different approaches to immunisation. In the DDR, as in most other socialist states and some Western countries, childhood vaccinations had been mandatory since the early 1950s, and all children received a series of standard vaccinations set by the Ministry of Health. These vaccines were administered to children directly in crèches and schools, while adults were vaccinated in the workplace. Individuals who did not want to be vaccinated or have their children vaccinated (which primarily occurred for religious reasons) could obtain an exemption after consultations with a physician and regional health officials. Vaccinations and health care more broadly were thus treated as a social task in the DDR, and a wide range of societal actors, whether doctors, teachers, or parents, ensured that all children received preventive medicine and care.

In the FRG, in contrast, vaccinations were recommended but not mandatory, and it was the responsibility of the families to arrange appointments with their paediatricians for vaccinations. The Standing Committee on Vaccination (STIKO), an honorary commission of medical experts, made vaccination recommendations which doctors were then asked and paid to administer, but public vaccination programmes were not implemented in schools or at the workplace. Hence, for doctors in the FRG, the incentive to vaccinate is primarily financial rather than medical.

The focus of today’s political discourse on the legality of mandatory vaccinations underestimates and often fails to recognise the crucial practical question of how the state can fulfil its obligation to organise vaccination for all citizens in an efficient and safe manner. However, there remains a question as to whether or not the basic conditions for a mass vaccination programme have been established in a given society. These include:

- Securing the resources to ensure that all citizens can be vaccinated. More specifically, this means producing or acquiring enough doses for all citizens, ensuring that facilities are safe and accessible, and employing enough medical personnel to administer the vaccines.

- Coordinating and monitoring vaccinations in an integrated system. One of the reasons why certain diseases continue to spread despite vaccination campaigns is that individuals forget to arrange a second or third vaccination necessary for full immunisation. This is a serious limitation of voluntary-based immunisation strategies in which individuals must keep track of and arrange their booster shots themselves.

- Maintaining the public’s trust in vaccinations and in the institutions and actors that provide them—that is, the state, pharmaceutical producers, and medical professionals. For instance, are private companies receiving public funding to develop vaccines that they will then patent and profit from, or is the state researching and developing vaccines that will be accessible and beneficial to all?

Mandatory vaccinations in the DDR were ultimately met by a public that was highly willing to be vaccinated. The use of coercion to increase vaccination rates—a hotly debated issue today—was thus not an issue in East Germany. Similar circumstances are evident in Cuba today, where the COVID-19 vaccination rate (roughly 90 per cent of the population) is one of the highest in the world, and yet no coercive measures have been employed.

Mandatory vaccination was understood in socialist East Germany not as a one-sided legal obligation for the citizen, but as the duty of the state and its medical institutions. Monitoring and achieving vaccination coverage to the greatest extent possible was a central priority for health care professionals, especially for physicians and authorities at the municipal level. Alongside the immunisation services that were integrated into workplaces, kindergartens, crèches, and schools, permanent vaccination centres were established where citizens could obtain information and schedule appointments for additional voluntary vaccinations, such as against influenza viruses. To this day, the willingness to be vaccinated against influenza remains significantly higher in East Germany than in the West.

Despite temporary difficulties in the production or import of vaccines, the DDR guaranteed universal child immunisation up to its dissolution in 1990. Furthermore, the number of diphtheria cases was drastically reduced, the fight against measles was advanced through booster jabs despite temporary setbacks, and the introduction of a vaccination against tuberculosis for all new-borns helped to significantly reduce the number of cases. The FRG, which had always been in a stronger financial position than the DDR, was also able to eradicate many childhood diseases, but its campaigns often progressed far more slowly than in East Germany, as is evident with the poliovirus.

Deutsche Demokratische Republik [German Democratic Republic]. Statistische Jahrbücher der DDR [Statistical Yearbooks of the DDR]. Berlin: Staatsverlag der DDR, 1956—1991; Rahlf, Thomas, ed. Deutschland in Daten [Germany in Data]. Bonn: Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, 2015.

9. The DDR’s International Cooperation and Medical Solidarity

Image 1010. In the late 1960s, after a long period of imposed diplomatic isolation, an increasing number of countries (mostly from the Global South) announced official relations with the DDR. In 1973, the DDR was admitted to the United Nations and participated constructively in its various bodies and organisations such as UNESCO and the World Health Organisation.

This photograph shows the arrival of workers from the city carrying a banner that reads ‘Colleagues from the Karl Liebknecht Berlin transformer factory are helping the first production cooperative with the harvest!’ The 1945/46, democratic land reform in the Soviet Occupation Zone secured food supplies in the dire post-war period while also fundamentally changing the system of land ownership in East Germany. Roughly 560,000 small farms emerged from the redistribution scheme, but they were often poorly equipped and supplied. Urban industrial and craft enterprises stepped in to help with the harvest in the emerging agricultural cooperatives.

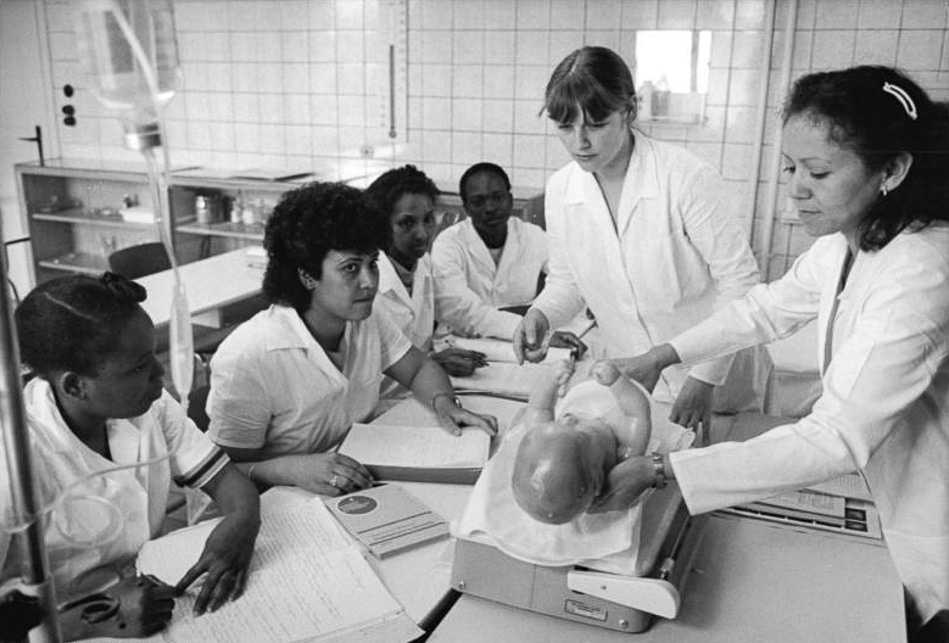

On 8 May 1973, the DDR became a recognised, equal, and active member of the World Health Organisation (WHO) alongside 145 other states. The FRG had been a member of the WHO since 1951 and with its claim to be the sole representative of Germany had hindered the DDR’s international cooperation in the field of health and its access to international resources. Following its admission in 1973, the DDR became a proactive contributor to the WHO, hosting the organisation’s 1981 Regional Meeting for Europe along with numerous WHO workshops. It was also actively involved in the WHO’s Health for All by the Year 2000 programme, especially on the concept of primary health care at the 1978 International Conference in Alma-Ata. DDR experts were sent to the WHO as delegates, while foreign students came to study in the DDR on WHO scholarships. Furthermore, fifteen medical institutions and projects in the DDR were certified as WHO Collaborating Centres, which supported the WHO’s global programmes by conducting research, collecting data, and fostering the exchange of scientific and practical experience.

In addition, cooperation between the socialist states was intensive but also limited by differences in each country’s capabilities. The DDR, for instance, supplied many medicines as well as medical equipment to the Soviet Union and its allies, while several thousand doctors from the DDR received specialist training in these countries.

Image 1111. In this article, copied from an entry in Dr. Rüdiger Feltz’s Nicaragua diary on 15 March 1986, the Nicaraguan press reports on the construction of the Carlos Marx Hospital, which started as a triage tent and was soon expanded into a fully functioning hospital. The hospital’s construction as well as the training of its staff and provision of its equipment and medicines were organised by DDR officials and financed by donations from DDR citizens. It was one of East Germany’s largest solidarity projects.

The DDR’s internationalist solidarity with countries throughout the Global South included numerous projects in the health sector. There were contractual agreements with over 40 countries and national liberation organisations, such as the South West African People’s Organisation (SWAPO) and the African National Congress (ANC). The spectrum of the DDR’s medical internationalism included supplying medicines and equipment, deploying doctors and nurses overseas, training and further educating international personnel in the DDR, and building and operating hospitals.

For example:

- The DDR-Vietnam Friendship Hospital, today the Viet-Duc (German-Vietnamese) Hospital, in Hanoi, Vietnam was supplied with medical materials by the DDR as early as 1956.

- The Carlos Marx Hospital was built in Nicaragua in the 1980s and largely operated by DDR medical and technical experts. By 1989, there were approximately 90 employees working there, including 25 doctors and 23 mid-level medical staff from the DDR.

- Over 50 doctors and specialists from the DDR constructed and operated the Metema Tropical Hospital in Ethiopia from 1987 to 1988 to treat drought victims.

- Angola received 27 ambulances through DDR solidarity donations in 1975. In a rehabilitation centre in the capital city of Luanda, DDR medical personnel treated wounded combatants of the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA). The centre also operated as a school to train local nurses and doctors.

- The DDR sent specialists to Cambodia (the 17 April Hospital), Mozambique (the towns of Chimoio and Tete), Algeria (Frenda, Mahdia, and Oran), the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (Aden), and Guinea (the orthopaedic-technical centre in Conakry). DDR paediatricians also treated patients at the National Union of Tanganyika Workers’ clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

Image 1212. The DDR’s Dorothea Christiane Erxleben Medical School, named after Germany’s first female medical doctor, emphasised medical pedagogy. The objective was to train students so that they could in turn teach trainees in their home countries, thereby promoting the development and autonomy of local health care systems.