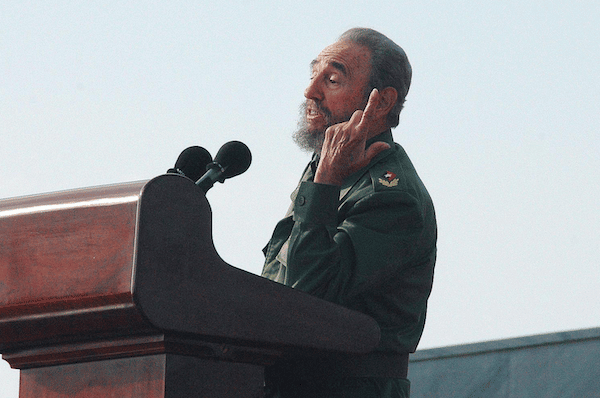

In the immediate aftermath of the recent devastating earthquakes in Turkey and Syria, Cuba dispatched medical teams to the affected areas to provide care to victims. Their departure was marked by a farewell ceremony, which featured a large photo of Fidel Castro. It was quite appropriate, for the international medical solidarity which Cuba regularly extends to countries throughout the world is the brainchild of the late iconic leader himself, who, in 2003, proudly proclaimed that Cuba does not drop bombs on other countries but instead sends them doctors.

Though Castro retired from his official duties as President of Cuba 15 years ago to the day, he has continued to remain a leader in solidarity and in peace. Cuban doctors were sent to more than 70 countries over the years, including nearly 40 different countries in 2020 to help in the fight against Covid-19. In 2010, even the New York Times acknowledged Cuba’s successful campaign against the cholera epidemic which broke out in Haiti after another earthquake. In 2014, the Times similarly gave credit to Cuba’s leadership in successfully fighting Ebola in Africa:

“Cuba is an impoverished island that remains largely cut off from the world and lies about 4,500 miles from the West African nations where Ebola is spreading at an alarming rate. Yet, having pledged to deploy hundreds of medical professionals to the front lines of the pandemic, Cuba stands to play the most robust role among the nations seeking to contain the virus.

Cuba’s contribution is doubtlessly meant at least in part to bolster its beleaguered international standing. Nonetheless, it should be lauded and emulated.”

In addition, patients from 26 Latin American and Caribbean countries have traveled to Cuba to have their eyesight restored by Cuban doctors in what was dubbed “Operation Miracle.” Among them was Mario Teran, the Bolivian soldier who shot and killed Che Guevara.

In 2014, Fidel received the Confucius Peace Award for his efforts in ending tensions with the United States and for his work to eliminate nuclear weapons. In addition, he played a key role in helping initiate, host and mediate the peace talks between the Colombian government and FARC guerillas which resulted in a peace deal in 2016, ending 52 years of brutal civil conflict.

The historic role that Fidel Castro played was always outsized for a country as small as the island nation of Cuba, and as a result, his impact was felt beyond its borders. One of the first countries that Cuba aided, back in the early 1960s, was Algeria, which had recently won its independence from France. As described by Piero Gleijeses, a professor at Johns Hopkins University, in his book Conflicting Missions:

It was an unusual gesture: an underdeveloped country tendering free aid to another in even more dire straits. It was offered at a time when the exodus of doctors from Cuba following the revolution had forced the government to stretch its resources while launching its domestic programs to increase mass access to health care. “It was like a beggar offering his help, but we knew the Algerian people needed it even more than we did and that they deserved it,” Cuban Minister of Public Health Machado Ventura remarked. It was an act of solidarity that brought no tangible benefit and came at real material cost.

This can be said of all of Cuba’s acts of international solidarity.

Meanwhile, what very few in the West know is that Cuba, under Fidel’s leadership and with the support of the USSR, played a key role in liberating southern Africa from U.S. and apartheid-era South African domination, and in ultimately ending apartheid in the country itself. It was for this reason that the first nation Nelson Mandela visited after his release from prison was Cuba. While there, Mandela lauded the nation as “a source of inspiration to all freedom-loving people.” Even the Washington Post recognized Fidel Castro as a hero of Africa.

After the Chernobyl disaster of 1989, Cuba took in and treated 24,000 affected children. Many of these individuals and their families still live there to this day. This act of solidarity cannot be understated given the economic conditions in the island nation at the time. While Cuba benefited greatly from the support of the USSR and Eastern Bloc after its 1959 Revolution, which Fidel led, by 1989 the Communist governments had fallen and aid from the USSR itself, which would collapse in 1991, was drying up. As a result of all of this, Cuba would enter what it called its “Special Period,” a time of great economic deprivation which many believed would lead to the collapse of the Cuban Revolution as well. But Fidel and Cuba hung on, and they continued to extend help to people around the world even while they were having trouble feeding their own people.

Due to the intensification of U.S. sanctions and the blockade of Cuba under President Donald Trump, and continued under President Biden, Cuba has now entered a time rivaling the “Special Period.” Even before Trump’s tightening of the sanctions—unrelenting U.S. economic war against Cuba, described by Havana as “genocidal,” had cost the country an estimated $1.1 trillion in revenue and had denied the Cuban people “life-saving medicine, nutritious food, and vital agricultural equipment.”

During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, the U.S. even blocked delivery of critical medical aid, including masks and diagnostic equipment, to Cuba.

The U.S. is punishing Cuba and the Cuban people not for their shortcomings and failures, but because of their very successes. And amongst the successes of the Cuban Revolution which Fidel Castro led even after officially stepping down from power, is Cuba’s unequaled solidarity to the world. Fidel’s “doctors, not bombs” speech implicitly contrasted his country with the U.S., which is by far the world’s largest arms supplier while helping less and less with humanitarian aid. Indeed, US sanctions are directly standing in the way of humanitarian efforts in countries like Syria—a country the U.S. continues to economically strangle even in the face of the recent earthquake.

Jose Marti, the Cuban revolutionary and poet who inspired Fidel Castro himself, once said that “there are two kinds of people in the world—those who love and create, and those who hate and destroy.” It is evident that Cuba, continuously inspired by the ideas and example of Fidel, is of the former type.

Daniel Kovalik teaches International Human Rights at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law, and is author of the recently-released book Nicaragua: A History of U.S. Intervention & Resistance.

Source: RT