She is a cashier at the local supermarket, she does repetitive and very exhausting labor, her joints hurt, she often works overtime for a miserable wage, insufficient to be economically independent. When she comes home, she has yet another tiring job ahead of her, because it goes without saying that she will cook, do the dishes, vacuum, do the laundry, make sure that all family members are taken care of, loved, and each given a fair amount of attention… She is a Roma woman, she is undocumented, she has children, she is thirty-two but looks much older, she suffers from a chronic disease, yet has no means to treat it. She lives in an informal Roma settlement without water, collects secondary raw materials all day with her husband and does this hard labor for barely eight euros a day. She also has a huge amount of work to do at home, because it goes without saying that housework is women’s work… She is unemployed, her partner physically and mentally abuses her, she regularly returns to her abuser because she has nowhere to go… She is thrown out of the public toilet on the pretext that as a trans person she allegedly endangers “biological” women… She is an activist in an organization and is assigned administrative and secretarial jobs more often than her male colleagues… She is a sex worker, a socially unrecognized and unprotected worker, non-unionized, she experiences various forms of violence, of which the most frequent is her clients’ refusal to pay her… She is a kitchen worker in a small fast-food restaurant, a paperless immigrant, forced to suffer sexual harassment from her boss because she is afraid of deportation, and without a job she cannot support herself and legalize her status… She is an activist in a feminist organization and the women in structurally higher positions of power mob her, emotionally and intellectually degrade her because of differing viewpoints, she comes from the working class and is threatened with losing her job… She is a secretary in a small company, she is pregnant for the second time and is not sure if she even wants a child, but social norms compel her to conform to the role of a good wife and mother… She is one of the raped, brutally murdered women who work in maquiladoras and another anonymous figure in the newspaper columns… She is Indigenous and lives with her community next to a polluted river into which a large company dumps waste. The community used to largely subsist on the fish they caught there, but now everyone is dying of malignant diseases… She is an unemployed mother of two, and her husband, who was channelling his anxiety, caused by insecure and miserably paid work, into violent behavior at home, was reported to the police by the neighbors. She and her children have been left without a minimum means of subsistence and do not have the opportunity to visit him in prison which is hundreds of kilometers away… She is a homeless woman who used to sleep on a park bench. She was forced to squat with her hands above her head, to allow herself to be felt up all over her body and to place herself in various degrading positions while she was being searched and was forced to undergo other manifestations of police violence… She does the same job as her colleague but is paid 20 percent less… She does not want to be a mother, her social environment passes judgment on her and the gynecologist claims that her maternal instinct should have already awakened at her age… For a long time, she thought that she was to blame for all the sexually connoted insults… She is a Black woman and did not receive anesthesia due to the racial stereotype that women of color are tougher and more durable… She is accused of not screaming enough for the judge to assess that it was a case of sexual assault, and the attacker was released… She is a trans woman and was expelled from the sports team under the pretext that she was born a man and that she has a sports advantage due to male hormones… She is only fourteen years old, yet there are no protests against her becoming a mother and there are no accusations of rape, because psychologists and the government officials have called it a “Roma tradition”… The repeated groping and spanking of a twelve-year-old girl by two of her classmates is not violence, they say, but an expression of pubertal hormones and childish infatuation… She works a part-time job from home, there is no clear boundary between her free time and working hours, she is available to the agency nonstop, and at the same time she takes care of her minor children and a sick mother…

~

The gendered forms of violence in capitalist-patriarchal societies are, obviously, related to what is habitually recognized as violence against women. But as we do not assume that there is a coherent, much less biological or natural entity that could simply be called women, here we will use the category “women” descriptively. By using the term “gendered,” we will try to point out that both sex and gender are normative and artificial identifications. Being a cis woman, lesbian, trans woman, nonbinary person, man, and so on, is determined by socioeconomic, cultural, political and historical frameworks, while the normative ethos which imposes that gender dimorphism is beneficial for the mode of production and the gender division of labor that arises from it. Sex as a male-female empirical given fact does not exist. Sex is assigned at birth, then it is adopted or rejected, it is shaped by a whole web of coded behaviors, repetitions, rituals, and normalization practices, it is socially imposed and molded into the heterosexual sex/gender dimorphism. Therefore, sex is nothing natural, but something that is naturalized. To that extent, a “woman” is not a clearly recognizable empirical category with XX chromosomes and the ability to give birth—rather, to be a woman implies a series of complex processes that gender a large group of people as women. Therefore, gendered forms of violence do not refer only to those who society recognizes as women, but to all the “abject” who recognize themselves in that category, as well as to other subordinate identifications that are constituted in a similar way, and intertwined with gender-based normalization, disciplining and oppression.

Gendered forms of violence are multiple and mutually intertwined: from femicide, domestic violence, the denial of choices concerning one’s own body and the attacks on reproductive autonomy, and obstetric violence, through sexual harassment, violence suffered by sex workers, violence suffered by transgender, gender-nonconforming, and other LGBTQIA+ people, and all the way to imposed gendered, racialized, often internalized norms of existence, expectations, stereotypes, discriminatory discourse, and other forms of marginalization and hatred related to sexuality, physical appearance, skin color, age, physical abilities and so on. Gender-based violence is ubiquitous and is often accompanied by other forms of violence that enable and situate it—instances of disciplining that are constituted by the normativization of heterosexual relationships and traditional family nuclei; subjugations in the name of imperialist and colonial divisions of the world; symbolic dimensions of violence; biopolitical violence, state, military and police violence; ecological violence which is affecting us at alarmingly high rates and so on.

In order to theoretically consider the logic that generates and reproduces gendered forms of violence, it is not enough just to observe and enumerate empirical phenomena, it is necessary to address their connection through the consideration of the structural conditions of the possibility of violence. Today’s societies around the globalized world, regardless of historical-geographical specifics, are primarily connected by capitalist relations that enable the reproduction of capital. To that extent, various forms of gender-based oppression are essentially directly or indirectly bound into oppressive patriarchal labor-capital relations and the consequent violence they produce, that is, the structural or systemic violence that capitalism reproduces in specific social formations. The relations between exploitation and power situate all social interactions and relations, and the human being itself, Karl Marx argues, represents a set of intertwined social relations. In order to ascertain why gender-based violence exists, and what mechanisms produce and reproduce it through nation states, we must therefore seek an answer within the concrete historical analysis of capitalism and the structural logic of capital accumulation.

This is sometimes not easy to perceive, because the violence of capital in capitalist societies does not appear as an excess, an aberration or as an anomaly, but as a norm. The compulsions and violence of the capital relation, which are primarily established as economic, are a regular instrument of subordination and discipline, something that has been stabilized by continuous repetition and pressure in such a way as to pervade every pore of our societies, embedded in our ways of thinking and perceiving, that is co-structuring our desires, language, permeating our bodies. It does not look like violence, but rather like a free contractual relationship. However, the violence of capital does not only rule over production in the narrow sense, and is therefore never only economic. Because of the fact that society as a whole is established to allow for the dominance of the capital relation in all spheres, this violence is structural. Gendered forms of violence are, in this sense, part of the package of violence by which capital maintains, reproduces and supports existing social relations. They are a part of the coercive and violent mechanisms that enable the functioning of the entire system, as well as the overcoming of its own crises and ruptures. Therefore, when speculating about gender-based violence, it is necessary to consider the nature of capitalist-patriarchal relations, property issues, and other pillars of capitalism, and to address the consequences of the supposed independence of productive from reproductive work, as well as the divisions within the working class. We will therefore try to point out the strong links between gender-based violence and capitalism.

How We Think of Gendered Oppression

In order to not only describe various forms of gendered violence, and its connection to other forms of violence, but to also provide a corroborated explanation, critical analysis, and argumentative base, the array of gender-based violence would have to be thought of from within a theory that roots gendered oppression in conjunction with the social system. The issue of how to think about gender-based violence is, therefore, an issue having to do with the critical theoretical framework. In this essay, we will try to think about violence from a framework that not only explains the phenomena systematically, scientifically plausibly, and consistently, but also indicates guidelines for political mobilization and emancipatory world change. Therefore, we will start from the key premises of a theory that coherently, analytically and fruitfully explains gender relations in capitalism: from the theory of social reproduction (TSR). Although the concept of social reproduction is widely used in the sphere of thought, we look at a specifically Marxist orientation, which was later called the theory of social reproduction, and which developed an analysis and critique of gender oppression, demonstrating in what way it is capitalist.

The theory of social reproduction considers the work, activities, practices, compulsions, and relations that enable and constantly renew the system, and reflects on gender oppression as an inseparable lever of the mechanisms of its existence and reproduction. It analyzes the capitalist social whole, in which oppressive forms are firmly bound and permeate both production relations and the broader social formation in which the capitalist system of production dominates. In this way, TSR enables the understanding of various forms of exploitation, subordination and discipline within the entire social system, without falling into the errors of two-systems, three-systems, or multiple-systems theories.2

Anchored in the conceptualization of social totality, the theory of social reproduction reveals different lines of separation and differentiation, and above all a division—which arose with capitalism—into production and reproduction. The social system is therefore thought of as a totality that has historically been established by the rift between production and reproduction, which is why we try to explain what are the activities, work processes, and dynamics that take place in both of these fields, and what defines the nature of their relation. In terms of the sphere of production, Marx presents us with a critical analysis of the way in which the capitalist system of production is structured and reproduced through the dominance of labor that creates surplus value for capital (profit-making) in coercive conditions, and of the structural violence that such a system generates. However, in terms of supplementing the explanation of the sphere of reproduction and the work that takes place in this field, it was necessary to wait for TSR in order for gender-based oppression to be scientifically grounded and understood as an inherent part of capitalism. TSR, therefore, explained the realm dominated by reproductive work, that is, work that creates, maintains and regenerates human life (life-making). In this way, TSR has allowed for a better understanding of how the entire social formation of capitalism is also supported through other relations that do not stem directly from capital-labor relations, yet still enable them.

In order for the system to produce and reproduce itself, as well as overcome its own crises, in addition to the production of commodities and the creation of value for capital, it is necessary for labor power itself to be produced and reproduced. No worker in the world can either appear in the workplace or produce value for capitalist enterprises unless they are first produced and reproduced themselves as labor power. They have to be born and already formed—in terms of satisfying not only basic physical, but also intellectual, affective, and all other human needs and desires, and in terms of acquired skills, abilities, competencies, education, and so on—so that it is possible to employ them and engage them in waged labor. They have to be able to return to work every working day and carry out their work obligations anew; they have to be well-rested, well-fed, regenerated, and able to get to the workplace. They have to develop a certain minimum of characteristics, skills, qualifications and knowledge with which they will appear on the labor market as employable. They have to be mentally and emotionally capable of reappearing in the workplace over and over again, which requires various forms of leisure, hobbies, entertainment, fulfilling activities, and meeting human needs. Thus, in order for labor power to be able to (continue to) create value for capital, it has to be produced and reproduced itself, and all this requires series of small and large activities, that is, labor.

The sphere of reproduction consists of activities that are types of work, not just forms of love, affection, and selfless giving, and these activities in capitalism have a gendered dimension because they are imposed and socially constructed to be performed mostly by women. While forms of wage labor—that is labor that produces commodities and enables the creation of profit—are performed in the formal-economic sphere of production, forms of reproductive work that produce labor power and human life are only partially performed in that sphere, partly in the public-state sphere (in periods of capitalism that are more oriented towards welfarearrangements), and for the most part they are imposed on women in working-class households as unpaid work. This work therefore mainly takes place outside the narrowly understood system of production, it is constructed as something that is supposedly natural, implanted in beings called women, and is often seemingly invisible as work. Namely, it is taken for granted that the fact of women doing the dishes, cooking dinner, giving birth, and raising children, all while juggling a myriad of other obligations within households, is purely a manifestation of love, not labor. Reproductive work which is gendered and further pushed into the sphere of the household and family in this way, does not directly create surplus value for capital, but supports it by the fact that the capitalist can count on workers to reproduce themselves without him having to pay for it. The arrangement is constituted precisely in this way in order not to hinder the increase of profits and to be advantageous for capital. Theory of social reproduction therefore seeks to explain the intrinsic relation between waged labor and reproductive work, using the framework of Marxist labor theory.3 Also, as TSR cannot be relegated to an abstract academic theory, but is concerned with political practice, it points to new places of resistance, struggle, rebellion and, hopefully, revolution. These gendered forms of labor take place outside the narrowly limited space of production, therefore the places of struggle are not only factories and formal workplaces, but all places where reproductive work is carried out: neighborhoods, public parks, public transportation, public places of fun and entertainment, public hospitals, community health centers and pharmacies, public libraries, clubs, workers’ holiday resorts, campsites, public cafés, and so on.

Gender-based oppression therefore has its structural place within capitalism and is inextricably linked to class exploitation—which is always racialised and heterosexualized—as well as to other oppressions, which are the conditions for the possibility and endurance of the system.

What about Intersectional Feminism?

The connection between gender-based subjugation and violence and their relation to racial, class, and other oppressions has also been the topic of other feminist currents, of which one of the most popular and most readily used today, especially in academia, is intersectional feminism. Intersectional feminists emphasize the intercrossing and traversing of multiple forms of oppression (for example, along the axes of race, gender, disability, sexuality, and so on), which are refracted and materialized as violence upon the bodies of individuals. This feminist approach can help in seeing how systemic injustice and social inequality occur on a multidimensional basis, that is, “intersectionality holds that the classical conceptualizations of oppression within society–such as racism, sexism, classism, ableism, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia and belief-based bigotry–do not act independently of each other. Instead, these forms of oppression interrelate, creating a system of oppression that reflects the ’intersection’ of multiple forms of discrimination”4. The intersectional approach primarily sought out to encompass personal identity and structural issues concerning privilege, oppression, and justice.

Susan Ferguson and David McNally believe that intersectionality indicates the complexity and heterogeneity of the experiential world, described by identifying “key social, political, economic and psychological dynamics that sustain patriarchal, racialized, and settler colonial relations, to name but a few,” and that some of the best analyses by intersectionalists point to the impossibility of separating and isolating any series of oppressive relations (Ferguson, McNally 2016). However, along with Lise Vogel 5 and others, they also point out that intersectional theory has failed to theorize the social totality, that is, the totality of the processes through which individual social relations intersect, regarding it as neutral and liberated from relations of power. Intersectionality puts forth a world in which race, gender, and other oppressions intersect, producing a reality that is, in the words of Tithi Bhattacharya, “latticed–a sum total of different parts,” an aggregation of “separate systems of oppression or even separate oppressions with only externally related trajectories” (Bhattacharya ed. 2017: 17).

Although this is a relatively heterogeneous theory, most intersectional theorists are primarily exhausting themselves in describing the effects of oppression, while simultaneously not taking into consideration the logic of these intercrossings and intersections, the reasons behind specific or identical intersections, the reasons for specific ways of reproducing specific oppressions in certain parts of the world, as well as not considering whether, for example, the struggles against racism and sexism are internally or externally linked.

Further more, intersectional feminism often approaches class as just another identity designation in a row, and not as a structural relation, thus minimizing class as an issue, and reducing it to mere “classism.” In this way, class is primarily viewed in terms of social stratification, that is, through socio-economic status determined by income, lifestyle, and so on. Such identity attribution, in turn, leans more towards a sociological description and classification, devoid of the theoretical context that maps the system or structure within which they acquire meaning. This facilitates the removal of political and theoretical focus from class as the structural basis of capitalism, one that is both a macro-level relation, as well as a social location independent of individual consciousness 6

Social reproduction theorists, who theorize the reproduction and regeneration of the working class within the process of capitalist accumulation, point out that class and the process of capitalist accumulation are crucial as long as capitalism depends on human labor power, and derives its surplus value from paid, underpaid, and unpaid human work. They specify that, although the categories of gender, race, and class are not comparable on an ontological level, class is a kind of marker that indicates the reality of capitalist accumulation, within which labor power is consumed and surplus value is produced.

The equating of various categories of oppression which was established by intersectionality, in order to nominally emphasize the importance of each individually, has in fact shattered the understanding of their particularities, as well as their structural and historical roles in the capitalist system of production. By claiming that class is not reducible to other oppressions, because it is a social relation of production and reproduction, we do not reduce gender or race to class as a mode of oppression—preciselyby insisting on distinguishing between exploitation (based on class) and oppression (based on different identities) we come to an understanding of not only the material roots of various oppressions, but also of the reasons for gender-based violence. It is precisely because social reproduction feminism shows how different oppressions are internally connected in the system of capitalism, that this approach more clearly outlines anticapitalist political intentions.

Intersections, as McNally argues in his essay “Intersections and Dialectics: Critical Reconstructions in Social Reproduction Theory” (Bhattacharya 2017), may be relatively random, but the same cannot be true of systems. In the system, all parts are arranged and integrated in ways determined by the other components. For this reason, a system is always more than the sum of its parts. Gender oppression and violence have always been accompanied by the economic exploitation of waged labor, which was becoming compounded into a unison, historically concrete capitalist social formation. Therefore, even when they remain analytically distinctive if viewed at a certain level of abstraction, the racialized and gendered regimes of domination that produce and generate violence are constitutively and historically inextricably bound into capitalist exploitation.

Gendered Violence and Social Reproduction

We started from the framework of the theory of social reproduction, from which it is necessary to reflect on the forms of gendered violence in conjunction with structural or systemic violence. However, understanding that violence is systemic does not mean ignoring the specific layers, peculiarities, and manifestations of violence.Furthermore, this does not mean that one should think about separate types of violence in a hierarchical way, in the sense that primacy is given to certain oppressions and the violence they generate, to the detriment of others. Marxist feminism concluded the old debate about the primacy of gender versus class oppression by demonstrating how capitalism is equally perpetuated through class exploitation as well as through gendered, racialized, ethnic, age, national, and other relations of domination and subordination. Therefore, the specificity of gender-based violence has to be thought of as being intertwined with other forms of violence and disciplining (this is also highly emphasized by intersectional feminism), but in order to theoretically substantiate that, it is also necessary to reflect on its essential capitalist determinant, that is, on the structural preconditions of gendered forms of violence.

In this sense, gender-based violence is never entirely personal, interpersonal, and irrational, because there are structural conditions that enable, facilitate, and instrumentalize this violence for the purpose of reproducing the system. The fact that, for example, a husband beats his wife is not just a matter of psychology and irrational actions, because the husband and wife are also dramatis personae (character masks) that embody certain roles, places and positions in a structural framework that enables, encourages and supports gendered forms of violence. Therefore, as far as theory is concerned, it is not enough only to describe the violence perpetrated by the husband against the wife—one must also seek to understand the links between this couple belonging to a particular class and the social roles and framework in which bodily management and work discipline are firmly connected. The theoretical foundation of gendered violence cannot be a mere recognition of the phenomena and an ideal-type classification derived from them— rather, it is necessary to explain the material organization of life that is based on coercion and violence, and how it is systematically reproduced through different lines of subordination. Therefore, it is imperative to demonstrate how gender-based violence is shaped in conjunction with the processes of creating labor power for capital, and how other dimensions of oppression, beside the gendered, are involved in these processes (racialized, ethnic, age, sexual-identity, ability-based, colonial).

Female labor power, equally as much as male labor power, is placed within the relation of capitalist exploitation, which is in itself a kind of compulsion—that is, structural violence. However, additionally, the system compels women from subordinate classes into yet another (exhausting and absorptive) type of work, which is unpaid and is imposed on them only because society recognizes them in the role of women. This imperative, which is the effect of the capitalist separation of production and reproduction, this compulsion, and the normalization of unpaid reproductive work as “naturally female,” make up the gendered tonality of structural violence.

Households and family environments are, of course, only some of the possible places where reproduction can and does occur, yet they still dominate capitalist societies, because unpaid women’s work benefits the accumulation of capital. These gender-generated axes of separation within the private spheres of households and families assign a certain—no matter how small, large or symbolic—power to men. This power is real because it is socio-economically and institutionally supported: it is not merely an ideologeme nor can it be explained away by pointing at the expectations of men being the providers and breadwinners of families in capitalist societies. The point of the matter is that it is easier for men to find permanent and full-time employment on the labor market, and thus be more economically self-sufficient than women, who will more often be forced to be supported by men. Men may choose whether to use this power, depending on how deeply immersed in sexist culture they are—but structurally, everything is set up in order for them to be able to use it. And, of course, they will often do precisely that, frequently in an irrational way. The so-called masculine position of power often allows for some sort of exhaust valve and compensation for what they feel in regard to the structural violence of capital to which they themselves are exposed. The loss of power or advantages over which there used to be at least a certain degree of control, becomes a trigger for violent behavior. It appears to them that they at least have some kind of control, some amount of power in their homes. Of course, commanding this power turns them into ridiculous lords, because ultimately the real lord is Monsieur Capital. The entire gender-marked social order is also another way of separating and disciplining the working class, that primarily benefits capital.

Capital organizes subordination in different ways, and by organizing work according to gendered differences, a constellation is created in which men can have certain benefits and conveniences from said arrangement. However, here it is necessary to distinguish the structural level of the problem from what would be a matter of (convertible) attitudes and beliefs, because it is very likely that, in a system already ruled by fetishized relations, men are deeply imbued with systemic sexist logic:

A man would lose nothing, in terms of workload, if the distribution of care work were completely socialized instead of being performed by his wife. In structural terms, there would be no antagonistic or irreconcilable interests. Of course, this does not mean that he is conscious of this problem, as it may well be that he is so integrated into sexist culture that he has developed some severe form of narcissism based on his presumed male superiority, which leads him to naturally oppose any attempts to socialize care work, or the emancipation of his wife. The capitalist, on the other hand, has something to lose in the socialization of the means of production; it is not just about his convictions about the way the world works and his place in it, but also the massive profits he happily expropriates from the workers. (Arruzza 2014).

The separation of the spheres of production and reproduction, therefore, is primarily advantageous for capital, and not for men. This is because men are not a specific class, and do not exploit female reproductive work in a strictly Marxist sense; they do not extract the surplus value from their labor. Beings who are gendered and constructed as men and women are anchored in the system, while the system-producing, institutional and ideological tentacles create conditions in which a certain specific identity role is imposed onto workers. All this is institutionally consolidated by the subordinating effects of the “male wage,” which additionally force women to adjust to the role of an unpaid reproductive worker who primarily obtains funds through marriage. Namely,despite certain changes and the results of the feminist struggle, capitalist societies are still dominated by the family wage model of income assessment, unified family taxation, and social rights derived from partnership status and a unified family budget, which structurally push women into an economically dependent position.7 The breadwinner model has therefore not disappeared—often concealed in new variants through which women are employed and, yet again, dependent on their partner’s wages—it was merely adapted and reformed. Capitalism continues to produce the male breadwinner/female homemaker model, not only as an ideologeme that generates certain expectations regarding gender roles, but also as an institutional-legal and economic model by virtue of which a woman is being pushed into the position of an economically dependent person, thus maintaining the capitalist metabolism that breathes by separating production and reproduction.

With the forced domestication of women, much of the gendered violence, of course, becomes more difficult to control, precisely because it has been pushed into the private sphere. In this way, gender-based violence is privatized, depoliticized, and psychologized, and made more difficult to resolve; non-interference in intimate and family matters is preached, and women are placed in an even more vulnerable position. Violence wrapped in obscurity, its concealment, its seemingly completely irrational features, its reduction to the outcome of individual pathologies; fear, lack of understanding, ignorance, nonrecognition, avoidance, denial, and mystification; calling violence passion, calling violence love, repression, enduring jealous outbursts; trauma, internalizing guilt, discouragement, extreme helplessness—all of these reign in the domestic area of violence. Violence is presumed to be a personal issue, one which concerns exclusively the private individuals, their characters or attitudes towards others, and is therefore a personal and interpersonal matter, and by no means a political one. Here is what capitalism has facilitated: it has by and large painted gender-based violence as a personal matter, as something that supposedly does not concern the system; it has transformed it into something irrational, non-political, something that seems to have nothing to do with economic relations, something that seems like an exception in a system that is putatively nonviolent.

However, gendered forms of violence and harassment do not occur only between four walls. They are also perpetuated in public spaces, because women, being economically and politically inferior, are in the positions of those who are more vulnerable, who will remain silent and suffer violence so as not to lose their employment, a roof over their heads, material security supported by various family wage systems, and the entire gendered constellation of assigning reproductive activities. In that sense, the huge number of cases involving abuse, rape and killing of women in public spaces is not merely an outpour of individual pathologies, but one of the socially supported means of subjugating women. This is particularly evident in those cases of gendered forms of violence that have a strikingly instrumentalizing character, such as the repeated rape of women from oppressed communities.

Violence confines women to the domestic sphere and to their role in reproductive work. Male wage violence binds women to their homes; to the work of caring for and nurturing of the members of the household; to physical, mental, and emotional servicing and serving of the husband; and to other reproductive tasks. Violence that takes place in dark streets and unsafe spaces also serves to push women even deeper into the “safety” of their home spaces and bind them even more tightly to reproductive tasks, as all places outside the home acquire an aura of danger. Violence, mobbing, and sexual harassment in the workplace reinforce the position of women as merely a secondary workforce, dependent on the power of bosses, professors, doctors, entrepreneurs, judges, police officers and so on. As the whole range of coercion and aggression becomes even more hindering towards women’s work and professional capacities,, violence in the workplace helps to remind women that their place is primarily in the home and with the children. State/juridical violence, which discourages women from reporting violence, minimizes verdicts against the perpetrators and shifts women’s positions from victims to defendants, also partakes in constituting systemic gendered violence. This makes it even more difficult for women to escape the arena of domestic violence. Ideological violence which legitimizes different nuances of gender-based violence and mystifies them as love and passion also binds women to the roles of reproductive workers within their home. Acts of violence that are sometimes carried out even within organizations and groups that presumably stand behind emancipatory feminist principles, also discourage and depoliticize women, ultimately returning them back to “their place,” that is, into the home and the domain of reproductive work.

The capital relation, constituted by the rift between production and reproduction, creates economic and noneconomic sediments of coercion, through which the complete system is maintained. The entire arrangement is institutionally supported by the state and its apparatuses. This is evident not only from the fact that the state ensures impunity for male violence, but also from looking at more direct forms of state violence such as the criminalization of sex work, institutional support for the lower employability of women (that is, the higher employability of women in part-time jobs), the enabling of access to benefits only to heterosexual couples and families, conservative social policies that support childbirth, motherhood, and staying at home, and so on. The state is the essential instance that regulates the marriage contract and establishes heteronormative socio-legal family models that make women dependant, and nonheteronormative persons even more marginalized. Medical and psychiatric institutions also, as part of the patriarchal-capitalist system, generate gendered forms of violence, such as abortion bans, forced sterilizations of racial and ethnic groups of women whose children are undesirable, and so on. Acts of ideological taming and dis/approvals of certain gender and sexual roles further deepen the ditches of oppression that allow for direct physical violence, harassment, as well as microaggressions, in public spaces and workplaces.

Gendered forms of violence in the workplaces represent a part of the map that reveals to us the constitutive connection of gender-based subordination to exploitation and work discipline. How frequent, and almost normalized, sexual harassment is in the workplace was demonstrated to us by the “bottom-up” version of the MeToo movement. Female workers in the fast-food sector experience some form of sexual harassment as much as 60 percent more times than in other sectors. The gendered and racialized forms of violence in the workplaces of corporate players, such as McDonald’s, are enabled precisely by the well-established repertoire of disrespect and exploitation of both female and male workers: very low wages, the ban on union organizing, unpaid or underpaid overtime, lack of benefits, hard work that requires speed and repetitiveness, and exposure to injuries, burns, and toxic disinfectants.8

The division of social spheres and the work processes within them, and the ideologically emphasized division of roles that are supposed to conform to the gendered division of labor, are inseparable from racialized disciplining and exploitation, neo-imperialist subjugation, and other modes of oppression that maintain the dominance of the capital relation. As a result, not all women are in the same position, as they are neither under the same pressure of compulsions, nor are they equally exposed to violence. A poor Mexican woman who risks her life illegally crossing the border to secure her existence, only to labor as a seasonal plantation worker in the United States, is not in the same position as, say, a middle-class white teacher, despite the fact that the latter may also experience violence from her partner. The first one most likely has nowhere to go to escape from the violence, the second one has the material and symbolic means to get out of the vicious circle of violence and can do it more easily.

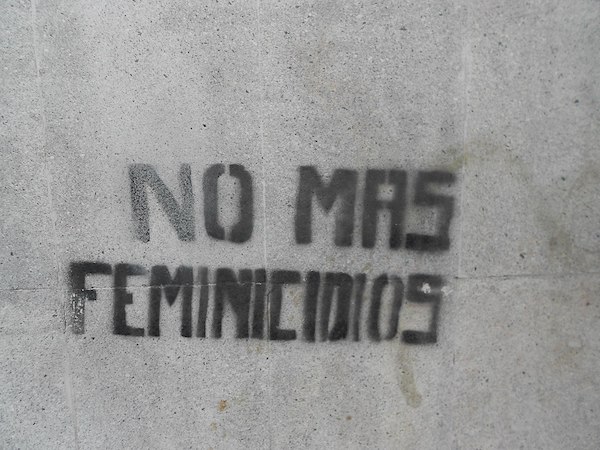

It is therefore not surprising that more nefarious forms of gender-based violence, intertwined with forms of neo-imperialist capitalist violence, occur more frequently in the Global South. We can take as an example the serial femicide that was going on in the city of Ciudad Juárez in Mexico since 1993, when around 370 women were brutally murdered in just over a decade. Most of the victims were young women who worked in maquiladoras, modern satanic factories; almost all of them were Latin Americans. The official narrative regarding this was that the murders were connected to gang wars and robberies. However, that doesn’t explain why exactly were women the ones to be murdered, why a huge number of those murders involved sexual assaults, why the murderers specifically targeted the most economically vulnerable, nonwhite, and Latina women, why it happened precisely in the export-oriented zone on the Mexican-U.S. border, and all this while the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was entering into force. Femicide is very much embedded in the framework of capital internationalization, which fundamentally relies on the neo-imperialist exploitation of cheap labor. Namely, these are jobs where labor costs are low, and labor legislation is nonexistent or extremely reduced; these are tax-exempt factories and therefore a paradise for capitalists; these are places in which the neoliberal work ethic is even more crystallized and where female workers most often live in gender-segregated dormitories, making them even more exposed to violence.9 The way in which the female labor force is disciplined in export zones is absolutely advantageous for international capital and for fabulous profits being churned out in such a milieu.

Gender-based violence is, therefore, located in the spatial and temporal distribution of capitalism’s framework. It is not the same in all areas of the imperialist world, nor in all periods of capital accumulation. Gender-based violence takes on different nuances depending on the imperialist cartographic difference between the so-called developed and underdeveloped countries, as well as with regards to the differences between periods of crisis and periods of growth. In developed countries, in periods of regular flows of capital accumulation, and in state models which are more oriented towards social welfare, the structural violence of capital—that is, the power of the “male wage,” of the breadwinner model, and the compulsion for women to perform reproductive work at home (regardless of whether being formally employed)—is sufficient enough to control and subjugate women. In controlling women, the state and capital can rely on normalized economic pressures, on the ideological orchestration of presenting work as love, and on the ever-present threat of direct physical violence. In underdeveloped parts of the world, in times of capitalist crisis, and in periods of capitalism marked by the collapse of welfare models, economic pressures and dependence on the “male wage” do not suffice. Seeing as the wages in these cases are low and precarious, the super-exploitation of cheap and predominantly unskilled labor is rampant, and the welfare services are withheld, the underdeveloped areas become “areas of the greatest concentration of capitalist and state violence against women” (Dalla Costa 2019: 60). Gender-based power is here to a greater extent supplemented with noneconomic coercion and, among other things, is built on the glorification of male authority and the cult of virility, a more open approval of gendered violence and more direct forms of physical violence. Disciplining women, therefore, is carried out by more cruel and conspicuous forms of violence (ibid: 62).

This is especially prominent in times of capitalist crisis, so it is no coincidence that statistics register a proliferation of gendered forms of violence during these periods. In the neoliberal variant of the capitalist crisis it is very obvious that the system, along with attempting to restructure production through austerity measures, seeks to restructure social reproduction as well: via the re-traditionalization of society and the heterosexual family model, the reshaping of gender identities, a more intensive criminalization of all practices and activities that “disrupt order,” an even greater domestication and privatization of reproductive work, and a more intensive disciplining of workers through all lines of subordination (therefore also through gendered forms of violence.) By producing structural unemployment—that is, the reserve labor force, which often includes precisely women, queer and trans people, people of color, disabled people, and so on—capital is again using the mechanisms of discipline and mutual antagonism, along with invoking duty and personal responsibility.

Gender-based violence in capitalism, therefore, should primarily be theoretically conceived as a mode of subordination which arises from the relation created by capital. Social reproduction theory provides a framework for the critique of gender-based violence and sexual harassment, that is intrinsically connected to the critique of capitalism. This critique is not focused only on the narrow segment of production, but is more inclusive. An analysis of the dynamics and spaces in which life is reproduced, an explanation of why some spaces seem to be safer and some more dangerous for women, and why everything is made in order to bind women even more to unpaid reproductive work in the service of the state and capital, allows the critique of capitalism to also focus onto what is happening outside the sphere of production, but is still deeply permeated by production relations. The theory of social reproduction therefore focuses on the critique of the social totality which supports these relations. It has to be able to explain, not merely describe, the structural features of social relations which are conducive to violence and which root sexism in power relations (or the illusions of power) in conjunction with tolerating alienating forms of work. This can help us understand the social relations in which, for example, a poor family used to be able to support themselves with only the husband’s salary, but after the neoliberal transformation of the former welfare state they barely manage to get by, even though both spouses work, and the wife does all the housework as well, while the husband complains about her finding a job and gets angry whenever she comes home late; social relations in which a man’s fear of losing the opportunity to be what is expected of him, that is, the fear of losing at least some sort of social control and authority, is manifested in a distorted way through the use of violence; social relations in which the commodification of sexuality is linked to work discipline; social relations in which the conditions for taking out a loan, imposed by financial capital, make it difficult to access housing, further degrade the subordinate and create social reproduction costs that are harder to bear; social relations that pit the subordinate against one another based on gendered and other divisions; social relations in which gender-based violence is another way of dividing the working class. TSR demonstrates that the connection between different forms of violence is not accidental and does not occur in an external way: gendered violence is inherent to the system. At the same time, various oppressions and instances of violence that support subjugation suppress the resistance of the oppressed and divide them on the basis of gender, race, ethnicity, age and other differentiations, thus maintaining the capitalist social system. Systemic compulsions are fundamental to the divisions of the subordinate: between the employed and the unemployed, between employees who are paid differently for equal work, between the male and female labor force, between white and nonwhite subordinates, between cis and trans persons, between the majority population and the Roma population, between the domestic and migrant labor force, and so on. If our enemies are not men but primarily capital, then the consideration of social arrangements by which capitalism essentially separates men and women, Black people, Indigenous people, people of color, and white people, cis and non-cis persons, older and younger people, domestic and migrant workers, and so on, should serve to unite us all in fighting against such an arrangement, rather than against each other. To that extent, gender-based violence, symbolic or discursive violence, violence of state-ideological apparatuses (the law, police, courts, etc.), violence against non-heterosexual persons, biopolitical violence that suppresses reproductive justice, and colonial and militaristic violence that reproduces the imperialist division of the world form the tightly interconnected skeleton of the structural or systemic violence of the capital relation.

What’s Practice Got to Do with It?

Although political strategies and outcomes do not derive directly, immediately, and easily from theory, it nevertheless has particular political implications, and is an important reference point for practice. Reflecting on gender-based violence from the theory of social reproduction demonstrates that this violence cannot be attributed in an essentialist way to men as such, but that the positioning and construction of certain persons as men is part of a structure that in some cases can give some power to those who identify as men. However, not all men in the system occupy the same position of power, nor do all women, and there are different systemic lines of subordination that enable, encourage, and generate different forms of gendered violence. Forms of gender-based violence gravitate around the gendered division of labor and other elements of the system of production, as well as around patriarchal heteronormative patterns, values, expectations, and ideologemes that reinforce the system. Namely, in order to maintain the capitalist division between productive and reproductive work, a naturalized heteronormative division of gender roles within the family nucleus has been established, which is also transmitted and consolidated in all other spaces outside the household. That is why gender-nonconforming, intersex and transgender people, “whose bodies are more difficult to instrument for reproduction and reproductive work,” (Gonan, 2018) are also among those who are most exposed to gendered violence, as they undermine the disciplining function of such a division. In this sense, the feminist struggle against gendered forms of violence that would be derived from the theory of social reproduction is not a struggle directed against the biologized entities of men, but against a system that enables the structural conditions necessary for different men, women, and others to be able to commit different forms of gendered violence.

The TSR perspective finds unsatisfactory: feminist currents that seek to suppress gendered forms of violence by directing solutions towards the struggle against men in general, while assuming that the categories of men and women are locked in an eternalized antagonism, and that patriarchy is a separate system; feminist currents that advocate market solutions in the struggle against gender-based violence, thus intensifying the violence of credit, the enslaving effects of debt, and other disciplining market mechanisms; so-called carceral feminism, which opposes gendered violence by relying on the police and seeks state-legal justice. Neither the police nor the state exist as neutral instances that could personify justice in capitalism, but are both key muscles without which the capitalist body would not be able to move, and are also constituted through a gendered dimension from the very onset of capitalism. The essential role of rights and laws in capitalist societies is that they are based on a formal equality which actually upholds, deepens, and conceals substantial inequalities. This is particularly apparent today, in the time of neoliberal reconfigurations of power relations, production, and social reproduction. Just as it was the case at the very beginning of capitalism and through all its historical moments, including the period of neoliberalism, “on-going forms of primitive accumulation continue to criminalize alternatives to wage labor,” (Adrienne Roberts 2017: 150). The shift from a welfare regime of discipline and punishment towards the neoliberal workfare regime even further intensifies the criminalization of poverty, of homelessness, and of activities that in any way disrupt the gendered order and distribution of roles.

Therefore, relying on the police as a supposedly neutral apparatus for combating gendered forms of violence is problematic from the perspective of TSR. For example, if a poor Roma woman who experiences violence from her husband calls the police, she is exposed to racialized forms of violence by the state apparatus, which enacts a completely different treatment towards poor and nonwhite people in that situation, than towards, say, an upper-class woman who endures violence. Transgender persons are also in some cases forced to “choose” between experiencing violence from their partner and experiencing various forms of police and state-structured violence.

If the criminalization of gender-based violence, despite being an understandable refuge, is not the best feminist reference point, then what are we to do? To begin with, instead of criminalizing violence, we could advocate for a more generous socialization of reproduction, which would at least loosen the structural conditions of violence. Instead of treating gendered violence as a problem that is for the police to handle, we could try and think of it as a social problem. In this age of absence, dismantling, and constant slashing of publicly organized social reproduction—the lack of compensation for state-supported social reproduction, its increasingly intensive domestication and familialization which contribute to the greater exposure of women to gendered forms of violence, and the generation of conditions for even greater dependence on the breadwinner model—one should demand exactly that which seems impossible within neoliberal coordinates: pressure on the state to provide as many and as accessible social services and spaces as possible, insistence on the construction of women’s shelters and safe houses, but also on providing workplaces for women and other subordinated groups and individuals, which would enable greater economic self-sufficiency.

For every form of resistance building, we clearly need organizations. However, if these organizations themselves also repeatedly replicate gender-oppressive models, then that warrants consideration as well, and efforts must be made to transform them based on feminist principles, not only with the aim of respecting ethical maxims (although this may be a vital programmatic component), but also building a politics that prevents, minimizes, and manages to handle gendered forms of violence. Rethinking the responsibilities of a community, transformative justice, and the feministization of left-wing and progressive organizations are among the models that more clearly define, recognize and address gendered forms of violence, but that also more clearly design mechanisms of protection against them.

It is necessary to think about the transformation of organizations in connection with the transformation of larger communities and the systemic framework in which violence is an inextricable thread. Namely, if violence is conceived as belonging to a separate dimension, as distinct from the system, then we will not locate long-term transformative points in which to resolve the issue of institutionalized gender oppression that is situated in capitalism in a specific manner. The struggle against gender oppression and gendered forms of violence—if they are understood as intrinsically linked to an exploitative hierarchical system of production that is always accompanied by the reproduction of a value system, in this case, the one of capitalism itself—thus must go hand in hand with the overthrow of capitalism. Reformist demands which work towards strengthening the rule of law, as well as the penal and punitive system, that is, strengthening the criminalization of violence, only work in favor of the restorative function of the capitalist system, which cultivates, generates, and encourages this violence. Demands which point towards the socialization of reproduction are also reformist, but rely to a greater extent on combined forms of resistance, rebellions, and feminist strikes, and advance more progressively in the direction of systemic change. Hence, the “small” steps inside the struggle must now already be firmly embedded in the “big” steps, and we must at least imagine the revolutionary horizon. The struggle against gendered forms of violence is therefore an inextricable thread within the anticapitalist struggle.

Translated by Vania Janković

Bibliography:

Aguilar Delia D., “Intersectionality”. In Marxism and Feminism, edited by Shahrzad Mojab. London: Zed Books, 2015.

Arruzza Cinzia, Bhattacharya Tithi, Fraser Nancy, Feminism for the 99%: A Manifesto. London, New York: Verso, 2019. Also, in Croatian: Feminizam za 99 %. Manifest, Zagreb: Centar za ženske studije, Institut za političku ekologiju, Multimedijalni institute, Udruga Bijeli val, 2019. Translated by Karolina Hrga and Martin Beroš. Available at: subversivefestival.com (Accessed: 16 May 2020)

Arruzza Cinzia, “Remarks on Gender”. In Viewpoint Magazine. Available at: viewpointmag.com (Accessed: 6 June 2020) Also, in Serbian: Aruca Čincija, “Primedbe o rodu”. In Stvar No. 9, (2017), Journal for Theoretical Practices, Gerusija. Translated by Andrea Jovanović. Available at: gerusija.com (Accessed: 6 June 2020)

Bhattacharya Tithi, “Explaining Gender Violence in the Neoliberal Era”. In International Socialist Review, Issue #9, (2019). Available at: isreview.org (Accessed: 17 August 2020)

Bhattacharya Tithi, Gender, Sexual and Economic Violence in Neoliberalism. SkriptaTV: video, 2019. Available at: slobodnifilozofski.com (Accessed: 21 June 2020)

Bhattacharya Tithi, “Mapping Social Reproduction Theory”, Verso Blog, 2018. Available at: www.versobooks.com (Accessed: 22 June 2020)

Bhattacharya Tithi (ed.), Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentring Oppression. London: Pluto Press, 2017.

Bohrer Ashley J., “Intersectionality and Marxism”. In Historical Materialism, Volume 26, Issue 2 (2018). Available at: www.historicalmaterialism.org (Accessed: 26 June 2020)

Burcar Lilijana, Restauracija kapitalizma: repatrijarhalizacija društva. Zagreb: Institut za etnologiju i folkloristiku i Centar za ženske studije, 2020.

Coleman Ann, “#Metoo Strikes at Mcdonald’s”. In Socialist Worker (September 2018). Available at: socialistworker.org (Accessed: 17 June 2020)

Crenshaw Williams Kimberlé, “Mapping the margins. Intersectionality, Identity Politics and Violence Against Women of Color”. In Stanford Law Review 43, no. 6 (1991).

Dalla Costa Giovanna Franca, Un lavoro d’amore. Rome: Edizioni delle donne, 1978. Also in Croatian: Dalla Costa Giovanna Franca, Rad ljubavi. Kućanski rad i nasilje protiv žena. Translated by Mia Gonan. Zagreb: Multimedijalni institut, 2019.

McNally, David, and Sue Ferguson. “Social Reproduction Beyond Intersectionality: An Interview.” Viewpoint Magazine, October 31, 2015. Available at: viewpointmag.com (Accessed: 16 July 2020) Also in Croatian: Ferguson Susan i McNally David, “Društvena reprodukcija onkraj intersekcionalnosti”, Zarez, 2016. Available at: www.zarez.hr (Accessed: 16 July 2020)

Ferguson Susan, “Social Reproduction: What’s the big idea?” Pluto Books Blog. Available at: www.plutobooks.com (Accessed: 27 July 2020)

Giménez, Martha E., Marx, Women, and Capitalist Social Reproduction: Marxist Feminist Essays. Historical Materialism Book Series, Brill, 2018.

Gonan Mia, Gonan Lina, “Transfobija i ljevica”, December 2018. Available at: slobodnifilozofski.com (Accessed: 17 August 2020)

Henderson Kevin, “J.K. Rowling and the White Supremacist History of ’Biological Sex‘”. Radical History Review, July 28, 2020. Available at: www.radicalhistoryreview.org (Accessed: 17 August 2020) Also in Croatian: Henderson Kevin, “J.K. Rowling i bjelačka supremacistička historija ’biološkog spola’”. Slobodni Filozofski, August 2020. Translated by Vir Lev. Available at: slobodnifilozofski.com (Accessed: 17 August 2020)

Lewis Holly, The Politics of Everybody. Feminism, Queer Theory, and Marxism at the Intersection. London: Zed Books, 2016.

Robertson Adrienne, Gendered States of Punishment and Welfare. Feminist Political Economy, Primitive Accumulation and the Law. London, New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2017.

Viewpoint Magazine, Issue 5: Social Reproduction, 2015. Available at: viewpointmag.com (Accessed: 17 July 2020)

Vogel Lise, “Beyond Intersectionality”. In Science & Society, Vol. 82, Issue 2 (2018). Available at: thecatalyst.uk (Accessed: 26 February 2023)

Vogel Lise, Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory. Brill Publishers: Historical Materialism Book Series, 2013.

Women and Revolution: A Discussion of the Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism. Edited by Lydia Sargent. Montreal: Black Rose Books, 1981.

Notes:

- ↩ This article was first published in Serbo-Croatian in the publication with contributions from over a dozen authors Ne/nasilje i odgovornost, između strukture i kulture: smernice za građenje nenasilnih zajednica (Belgrade: Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung Southeast Europe, 2020) (Non/Violence and Responsibility: Between Structure and Culture: Guidelines for the Construction of Nonviolent Communities). Several minimal interventions to this article were subsequently made by the authors. The English translation of the article was edited and proofread by Martin Beroš, and by Sarah Kramer from Monthly Review.

- ↩ Two-systems theory presupposes a distinct system of gender-based relations, most commonly called patriarchy, which is then in one way or another related to the system of production relations that is called capitalism and that is reductively thought of as a system of class relations. Three-systems theory, in turn, introduces a third system (based on race) into the explanation, and so on. The basic problem with two- and multi-systems theories is that they assume some sort of special gender/sex system in which men and women are in an asymmetric oppressive relation, as if something like that exists in pure form and does not change in different historical contexts. From this transhistorical starting point it is then very easy to slip into essentializing explanations of the supposed male-female antagonism. See more: Arruzza 2014; Vogel 2013; Women and Revolution 1981.

- ↩ This does not mean that there are no other types of work that cannot as easily fall into the categories of the “typical-capitalist” form of labor which creates surplus value or of the reproductive type of labor that is gendered, racialized, heterosexualized, etc. However, this Marxist-feminist insight has brought about the theoretical foundation of the gender-based dimension of labor, thus facilitating the understanding of how these types of labor relate to other forms of labor, and the reflection of a far more complex map of work in capitalism.

- ↩ From the Wikipedia entry for intersectionality from 2017 (accessed March 4, 2017), cited in Vogel 2018: 276.

- ↩ See Vogel 2018: 281-284.

- ↩ This refers to the structural/sociological definition of class as a class situation, leaving aside the processes of politization, i.e. class formation, for which consciousness is indeed very relevant.

- ↩ See: Burcar, 2020.

- ↩ “Four out of 10 fast-food workers face sexual harassment on the job.” Ann Coleman, 2018.

- ↩ This example also demonstrates that labor power is not always reproduced through a habitually structured household, capital does not always secure access to labor power through its regeneration, but rather through the replacement of workers when they become worn out, depleted. In areas where cheap labor power is abundant, this can be even more cost-effective than letting social reproduction be arranged through the gendered division of labor in households.