One of the stories dominating Canadian media right now—the baseless accusation that Beijing interfered in Canadian elections to secure Justin Trudeau’s victory—appears similar to the “Russiagate” hoax of a few years ago.

Russiagate, which was peddled by liberal elements of the U.S. media and political establishment following Donald Trump’s 2016 victory, groundlessly asserted that a foreign government to the East had meddled in supposedly pristine Western elections and tipped the scale in favour of their preferred candidate. That general outline also seems applicable to the anonymous “leaks” coming out of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) of late.

To both Trump and Trudeau’s opponents, the conspiracy theories simply make sense. Many U.S. liberals were so shocked by Trump’s victory that they refused to recognize him as a legitimate president, and the allegation that Vladimir Putin’s intelligence services had placed him in the White House let the Democratic Party off the hook for running such a widely despised candidate in Hillary Clinton.

In Canada, many conservatives continue to view Trudeau as a dictatorial, even communistic figure whose values don’t align with their myopic understanding of Canadian history. As such, the allegation that China placed him in power makes sense to them, despite the dearth of evidence.

Sinophobia has played a significant part in the ongoing non-scandal. While Russiagate borrowed from the deep well of cultural Russophobia in the U.S., the “Chinese election interference” story also has its roots in xenophobia—in this case, the “yellow peril” fears that many would have thought Canada had outgrown.

When paired with the acute decline of Canadian capitalism and the slow decay of the U.S. empire—the one-time imperial hegemon to which Canada has sutured itself—Ottawa’s anxieties about a power to the East are neuralgic, irrational, and grimly familiar. The Chinese interference fantasy is merely their latest manifestation.

The precarious balance of multiculturalism and xenophobia

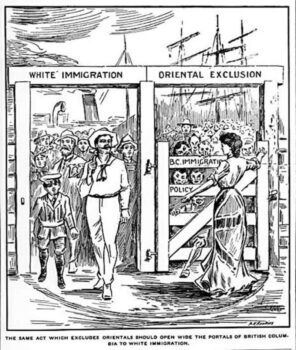

After the founding of Canada, Sinophobia and anti-Asian racism served as a way for the new nation’s leaders to define their vision of “Canadian-ness” as “whiteness.” While encouraging the immigration of white settlers, Asian immigration was stiffly curtailed on the grounds that it represented a threat to the whiteness of the state—a “yellow peril.” The head tax on Chinese immigration and the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act were two of the state’s most aggressive attempts to reduce Asian immigration in defence of the normative ideal of a “white” Canada. These views continued into the postwar era, with Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King declaring that Asian immigration threatened the “fundamental composition of the Canadian population.”

A cartoon encouraging the exclusion of Chinese immigrants appeared in a BC newspaper on August 24, 1907. (Image courtesy the Vancouver Public Library.)

Restrictions on Chinese immigration were not repealed until after the Second World War. Similarly, Chinese Canadians were not given the right to vote until 1947.

Multiculturalism as an institutionalized framework emerged in subsequent decades. In Canada and the World since 1867, historian Asa McKercher explains that the Canadian government’s move away from overtly racist immigration restrictions toward multiculturalism was partly motivated by Cold War geopolitics.

In decolonizing nations across the Global South, it was obvious that Canada’s claim to be a democracy with equal opportunities for all was not commensurate with the realities of its racist policies. On one occasion, the Soviet Union even countered Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s criticism by threatening to launch a complaint against Canada at the UN Human Rights Commission “highlighting racial discrimination faced by black Canadians, ethnic minorities, and indigenous peoples” in Canada. It was following criticism such as this that Canada began to open new immigration centres outside Europe, including in Japan, India, and Pakistan.

Multiculturalism was officially adopted under Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau. There were economic reasons for doing so. After all, it is hard to believe a government that had proposed the White Paper two years earlier—a document that called for the total assimilation of Indigenous peoples in Canada—cared about protecting the languages and traditions of different groups on principle.

As Justin Podur of the Anti-Empire Project outlines:

multiculturalism… has always carried both an anti-racist and a sinister element. It is based on the belief that people from any country of origin could become as ‘Canadian’ as the British colonists who seized it in the name of the English Crown. The resulting Canada would be a ‘mosaic of cultures,’ not a melting pot that pressures people to sever ties with the old country and assimilate as happens in the United States.

Multiculturalism basically represented the widening of the category of socially accepted settler, which undermined the normative idea of Canadian whiteness while simultaneously “try[ing] to lower the special status of First Nations down to the level of any other part of the mosaic and hide the fact that they retain sovereignty over the land.”

Canadian multiculturalism also served an important foreign policy goal: weaponizing diasporas against the targeted governments of their home countries. As Podur explains:

These diaspora communities of the mosaic are assumed to have homogeneous politics as regards foreign policy: their visible leaders and their community media are of course vocally against the Chinese government, but also pro-US sanctions and wars, anti-Communist, against Palestinian sovereignty, etc.

There were long-term economic considerations behind the Canadian state’s institutionalization of a system of multiculturalism. However, the recent uproar around Chinese election interference, and the public calls for Chinese Canadian officials to prove their loyalty to Ottawa over Beijing, shows that multiculturalism did not succeed in rooting out the entrenched xenophobia of the settler state.

From an Atlantic to an “Indo-Pacific” power

After the Second World War, Canadian leaders supported American predominance in Asia on the grounds that the region fell within the U.S. empire’s sphere of influence. As John Price writes in Orienting Canada: Race, Empire, and the Transpacific:

the Canadian government displayed a strong inclination to support the U.S. agenda in the Pacific regardless of the implications for the peoples there, for democracy, or for multilateral institutions. The rationale for this conduct was that Japan and Asia were within the U.S. sphere of influence, an imperial concept that still held sway.

Canadian leaders were not coerced into supporting U.S. aims in Asia. They backed them heartily on the grounds that “We were all Atlantic men,” as Canadian diplomat Charles Ritchie put it.

More recently, conservative think tanks and elements of the Canadian government have urged Ottawa to take a more aggressive stance in Asia, citing the amorphous threat of China which, at its core, is the Chinese threat to U.S. hegemony in Asia. Trudeau has by and large given these pro-confrontation forces what they want, deploying more Canadian troops to the Pacific, announcing an anti-China “Indo-Pacific Strategy,” and playing a lead role in the antagonistic RIMPAC 2022 exercises. Trudeau has also aimed to limit academic collaboration with Chinese scientists who reportedly have ties to China’s National University of Defence Technology (NUDT), while doing nothing to reduce Canadian universities’ far more significant collaboration with the U.S. military-industrial complex, which has sent tens of millions of dollars to Canadian academics and universities.

Imperial anxieties in a multipolar world

China’s rise has not only exacerbated U.S. anxieties about the American empire’s decline. Canadian elites have been feeling a similar sense of unease. This is because, for many decades, Canada has benefitted economically from an almost total geopolitical alignment with the U.S. By latching onto the U.S. empire like a remora, Canadian corporations and consumers have been able to drain profits and goods from the Global South through pro-business dictatorships and free trade agreements imposed by Washington.

Canadian Member of Parliament Han Dong in Toronto, June 12, 2014. (Photo by Rene Johnston/Toronto Star.)

Meanwhile, Ottawa’s military objectives have been served by the U.S. government’s globe-spanning collection of military bases, which has allowed Canada to step back from military confrontation and cultivate a benevolent peacekeeper image for itself.

Now the rise of China and Russia have brought a new era of multipolarity. At the same time, Western capitalism has been widely discredited to the people living under its regimes. Everyone knows that Canada, the U.S., and Europe are run by an unaccountable class of business aristocrats who, regardless of party, care nothing about the livelihoods of ordinary people. Whether it’s due to bank bailouts, industrial disasters, or devastating “greedflation” caused by the collusion of price gougers, these systems have largely lost their legitimacy. As University of Manitoba professor Henry Heller recently wrote,

[the West’s] representative democracy has transformed itself into oligarchy and a kind of liberal totalitarianism.

With the rise of China, the dawn of multipolarity, and the decay of Western capitalism, the Canadian elite’s anxieties have risen sharply. Taken together, these are fundamentally imperial anxieties, concerned not only with Canada’s economic decline but with the country’s global role and its privileged position under the lagging U.S. hegemon.

After the Second World War, Canada drifted away from the dwindling British Empire and toward the ascendant American one. As the U.S. empire declines, there is no up-and-coming Western empire that Canada can ally with to retain its global privilege, and Canadian leaders know it. These imperial anxieties in a multipolar world have contributed to an ugly, unashamed resurgence of Sinophobia in Canadian political culture, which is once again constructing Chinese people as threats to the very essence of the Canadian state.

A manufactured crisis

The “Chinese interference” story has all the trappings of a manufactured crisis. Unless one is willing to take the word of some anonymous “security officials” in the Canadian intelligence apparatus—an apparatus that has its own logic, motives, and agenda—it seems obvious that the story is without substantive import to Canadians. Even one of the CSIS “leakers” admits that China’s alleged interference did not influence the outcome of any Canadian election.

Al Jazeera columnist Andrew Mitrovica studied CSIS for his book Covert Entry: Spies, Lies and Crimes Inside Canada’s Secret Service. He found “a rogue agency rife with laziness, incompetence, corruption and lawbreaking.” He added that “too few reporters, editors, columnists or editorial writers in Canada have made the effort to understand how CSIS functions with impunity and hold it to account.” CSIS’s mendacity has been documented by many others, including Yves Engler, who wrote that in its call for an inquiry into China’s supposed interference, the NDP “is demonstrating a remarkable level of trust in leaks from an intelligence agency that lied about Maher Arar, Abousfian Abdelrazik and many others.”

Sources have contradicted themselves on key elements of the allegations. Global News sources alleged that China had covertly passed $250,000 to 11 federal cabinet ministers, whereas Globe and Mail sources said there was no evidence of such funding. Meanwhile, CSIS director David Vigneault has asserted,

We have not seen money going to 11 candidates, period.

The articles that make claims about specific MPs by name, effectively accusing them of being fifth columnists who are disloyal to Canada, do not provide any proof of their allegations.

Meanwhile, some of the claims made by anonymous sources don’t stand up to basic scrutiny. Some allege that Beijing wanted Trudeau to win, but wanted his power constrained by a majority government—a claim that makes no sense, because if Trudeau was a Chinese asset, they would surely want him to be as powerful as possible.

Others claim that Liberal MP Han Dong urged China to delay the release of Michael Spavor and Michael Kovrig because releasing them would help the Conservative opposition, but that showing “progress” in the case would help the Trudeau government. It is not explained how securing the Michaels’ release would have done anything but increase goodwill for Trudeau.

The Globe and Mail later reported that the transcript of Dong’s call with the Chinese consul-general, when he allegedly called for the delay of the Michaels’ release, showed no evidence that he’d made such suggestions. For his part, Dong has retained a lawyer and plans to sue Global News for defamation.

As Davide Mastracci writes in Passage, the Global article on Dong “relies almost entirely on anonymous CSIS sources. It fails to confirm many of the allegations these sources make. It doesn’t attempt to address any of the inconsistencies in their stories. It has no interest in interrogating why they may be making the claims.”

In short, there are no hard facts that confirm the core of the allegations—and yet, that hasn’t stopped scrupulous Canadian media outlets from breathlessly reporting on the accusations.

A degraded political culture

Deep-seated Sinophobia in Canadian culture, mixed with anxieties about economic and imperial decline, have converged to produce the ongoing “Chinese interference” story.

It is unclear why CSIS chose this moment to accuse Chinese-Canadian MPs of disloyalty to Canada, but the fact that much of the media and political class has embraced these accusations and called for an inquiry shows how degraded this country’s political culture has remained. The Conservatives have unsurprisingly amplified the anonymous allegations, but even NDP leader Jagmeet Singh called for Han Dong’s removal and a public inquiry into Chinese interference.

While we don’t know the exact reasons why CSIS chose to make these accusations, it is clear what they have produced: more anti-China frenzy, “yellow peril”-esque fears of Chinese infiltration through government officials and community organizations, and plenty of media coverage implying that Chinese-Canadian MPs are fifth columnists of Beijing.

Perhaps this was the agency’s goal. During the first Cold War, Western intelligence agencies spent enormous time and resources germinating fears of communist infiltration in the minds of their populations. It wouldn’t be far-fetched to think that, in the second Cold War, organizations like CSIS would return to tactics such as these.

What is different about the current Cold War, however, is the domestic and global context in which Canada finds itself. Economic decline has discredited capitalism to a large section of the population in the West, particularly young people. Even a series of polls by the right-wing Fraser Institute found that “there is a clear net preference for socialism [over capitalism] amongst those aged 18—34” in Canada, the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

It is also undeniable that the U.S. government views China’s economic success as a threat to its imperial hegemony. By extension, Ottawa views China’s rise as a threat to the Western hegemony from which elements of the Canadian population have derived huge benefits.

We need to view the “Chinese interference” accusations in light of the xenophobia, economic decline, and imperial anxieties that are resurgent in Canadian culture at this moment. When we take this holistic view, it becomes clearer than ever that the scandal on which Canadian media and politicians have expended so much time and energy says far more about the current state of Canada than anything else.