I’m sitting at the bar of Blackmarket Hall in Rome, a trendy food and drink hang out not far from my new home in Monti. It’s Friday night and the joint is heaving. I’ve had a couple of glasses of wine and a whole world spins around in my head. I’m conscious that I’ve been inactive for a few months now, feeling exhausted, a bit overwhelmed by the practical chores my recent move necessitated. My brain felt dead. Yet sitting here, amid a crowded scene of noisy, young revelers, listening to seventies funk music boom out, tunes I remember first-time around, I knew I had to try to do something creative again soon.

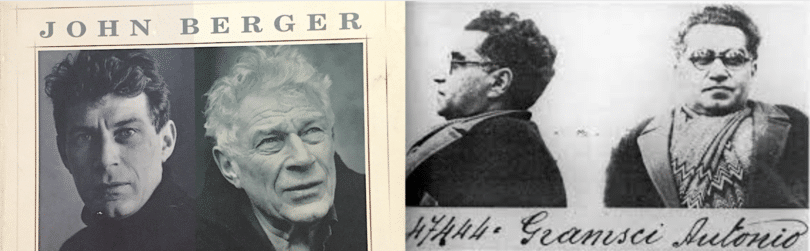

The feeling—a kind of urgency of the moment—was prompted by what I was reading. I had with me a copy of John Berger’s book of essays, The White Bird, from the mid-1980s, taking it along to offset my aloneness. A book is always a good cover for the solitary person in public, an effective disguise. I was in awe at how good these pieces were. White Bird’s most famous essay is “The Moment of Cubism”; but tonight, I guess I was having my “Moment of John Berger.” I remember John once telling me—or else I’d read it somewhere—that he’d hated White Bird; when it first appeared, in disgust, he threw it across the room, launched it like a missile. He never thought it any good. My God, what could he have been thinking? Was he talking about its form or content? Its content, after all, while previously published material, is as brilliant as I recall, maybe even better now than upon my first reading decades ago.

There are bits and pieces on Italy—John was always fond of neighboring Italy; for years he lived just across the frontier in Haute-Savoie, itself once part of Italy, traveling up and down the country extensively, frequently on his motorbike. (One journey is beautifully recreated in To the Wedding.) In White Bird, John talks a lot about Italy, about Danilo Dolci’s Sicilian Lives, about Italian painting and films like Open City and Bicycle Thieves, about having his rucksack stolen in Genoa from the back of his old Citroën 2CV car. There’s also a lovely evocation of the poetry and life of the Roman Leopardi, one of Nietzsche’s favorites, as well as a compelling essay on Van Gogh, called “The Production of the World.” This one wasn’t about Italy, of course; yet on my Italian Friday night, an essay I’d read many times, seemed to speak to me like never before.

John would have been roughly my age when he wrote about Van Gogh here. He confesses to feeling washed out, at a low ebb, metaphysically exhausted. I was feeling washed out intellectually, too, wondering what I’d do next, thinking I’d produced all I could, even talking about going into early retirement. I was still dizzy from my new life, living out a bit part in a Fellini movie, my very own 81/2, thrilling yet surreal, not feeling quite a whole number yet. I was suffering the same sense of unreality that John spoke about.

He’d hummed and harred about going to a meeting in Amsterdam, he says. In the end, he decides to go. And what transpires is a strange encounter with Van Gogh’s paintings, with cornfields and potato eaters, pear trees and peasants dozing under giant haystacks, all of it kindling something inside him, unleashing a rebirth of sorts. “Within two minutes,” he says, “and for the first time in three weeks—I was calm, reassured. Reality had been confirmed. The transformation was as quick and thoroughgoing as one of those sensational changes that can sometimes come about after an intravenous injection.”

“These paintings,” John says, “already very familiar to me, had never before manifested anything like this therapeutic power.” And so, that night, sitting alone at a bar in Rome, John’s own words, already very familiar, had never before manifested anything like this therapeutic power. Reading him was like being hooked up to an intravenous drip: forget the wine. The transformation was immediate. Reality had been confirmed. I snapped out of it, would get writing soon. I’d start that night; in fact, already had started that night, scribbling in my mental notebook, beginning to write this.

After I’d finished dinner and requested il conto, the young man behind the bar, who’d been serving me all night, asked what I’d been reading. I showed him White Bird, enunciating the author’s name, an English writer and critic who died in 2017 at 90, and who, I said, was widely available in Italian. “Never heard of him,” he told me, almost apologetically. “That’s a pity,” I said, “because he’s really something, a knockout read. You should check him out, his novels and criticism.” I added that, actually, I’d written a book about him—a remark I immediately regretted, feeling like a drunken jerk, bragging about former glory days, like in the Springsteen song.

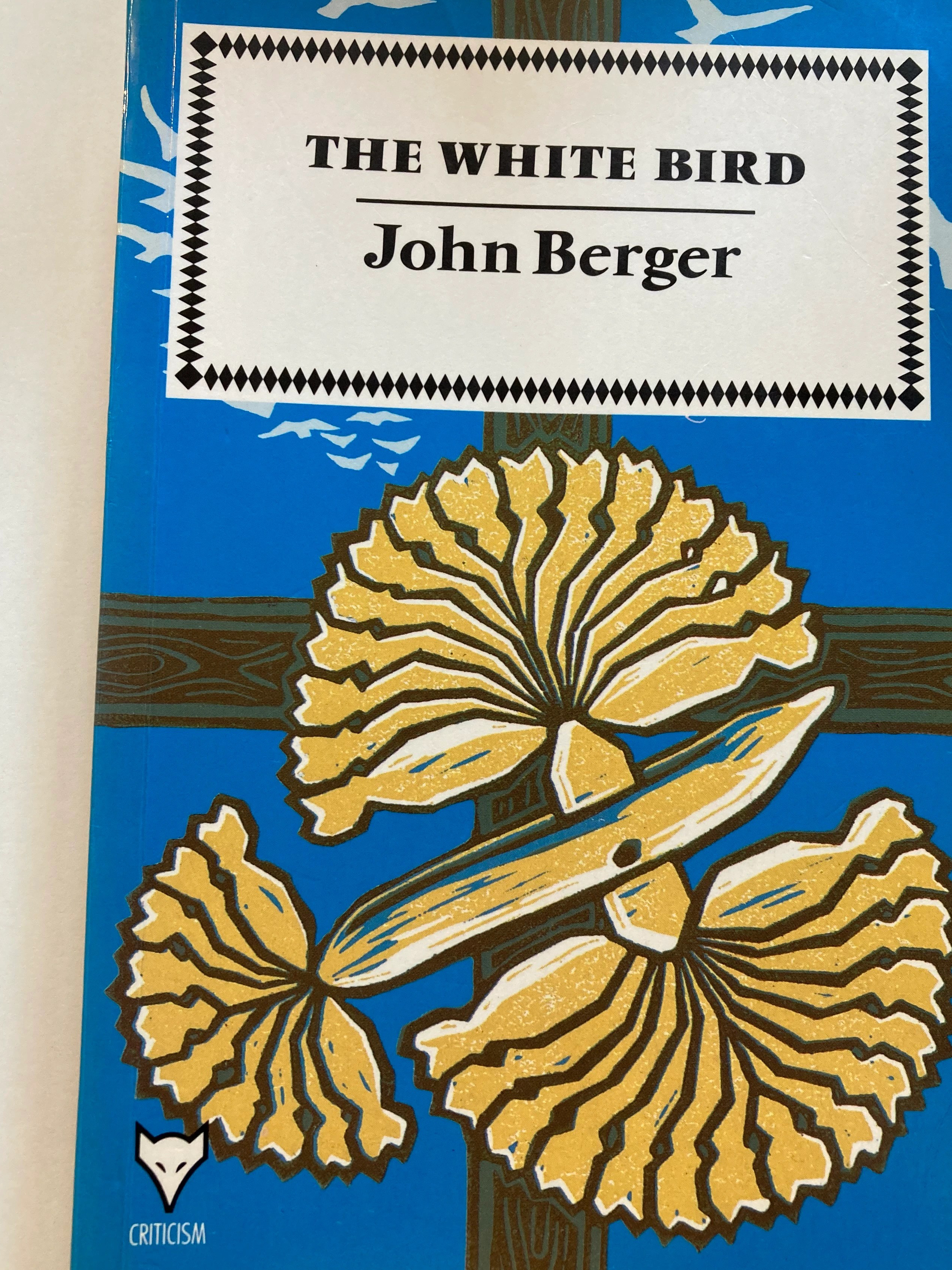

A week or so on, John was still with me, there in spirit. Or, better, I was still with him. When in Rome, I told myself…well, what better thing to do than to visit Gramsci, the great Marxist, whose grave lies in the city’s “Non-Catholic Cemetery” in Testaccio. Testaccio was a popular working-class neighborhood, housing thousands of industrial workers from nearby Ostiense, and probably best-known for Rome’s famous slaughterhouse, at Mattatoio, in its heyday Europe’s largest and most advanced. (Decommissioned in 1975 and partly renovated into an experimental cultural and arts center, with a farmers’ market, the huge complex remains mostly rundown, its old stockyards frequent hangouts for homeless populations.)

The Non-Catholic Cemetery is just a short stroll away. Like Paris’s Père Lachaise and London’s Highgate, it is a grave-spotter’s paradise. The English romantic poet John Keats is its most popular denizen, followed by his famous champion, Percy Shelley. Gramsci, who occupies a secluded southwestern spot, is third on the visitor’s roster. The day of my homage was searingly hot, over 40 degrees, and sitting on a wooden bench facing Gramsci, amid the din of cicadas, squawking birds, and mosquitos chomping at the bit, ancient cypress trees and pink flowers everywhere in bloom, I thought I’d landed on some distant tropical shore. The Aurelian city-walls, towering over one side of the cemetery, made everything feel like a magic kingdom surrounded by a vast moat, cut off from the crazy chaos of the rest of the city; the Egyptian pyramid of Caius Cestius, its 36 meters poking out between the shrubbery, only added to the sense of otherworldliness.

Gramsci had a truly torrid life, rotting in a fascist jail for a decade; yet his final resting place is lovely, serene in its elegance and simplicity. A small, upright stone slab reads:

GRAMSCI

ALES 1891 ROMA 1937

Its base is a marble casket, with a Latin inscription:

CINERA

ANTONII

GRAMSCII

Gramsci’s ashes. Gramsci’s sister-in-law, Tatiana Schucht, a Soviet citizen and sister of Giulia, the revolutionary’s wife, was instrumental in securing him a plot at the cemetery. She’d been a student in Rome, living with her father, Apollo Schucht, who’d fled Tsarist rule. Tatiana was devoted to her brother-in-law; and, in Giulia’s absence (in the Soviet Union), cared for him during his confinement. In 1938, a year after his passing, and with Mussolini’s approval, she managed to get him a three-square-meter plot at the “English Cemetery.”

In 1957, Gramsci’s ashes were moved to another, larger plot, its current location, where I’m sitting now. At the back of Gramsci’s headstone, I can see it if I bend my head round, is the name Apollo Schucht, Tatiana’s father, inscribed as a memorial, as well as Nadine Schucht-Leontieva, her eldest sister, who’d died in 1919. Tatiana is the great unsung heroine in the Gramsci saga, her brother-in-law’s political and emotional lifeline, not only burying him but keeping him alive, too, recovering all of his thirty-three notebooks, one of the most original and prodigious documents of western Marxism.

Next to me that day, sharing the wooden bench, is a man in his mid-twenties, wearing iPods, unperturbed about someone sitting so closely. We didn’t say a word to each other; there seemed no point. For a while, I savor the setting, the peace, the moment, my Gramsci moment. Then one of the best essays written about Gramsci comes to mind; no surprises it’s John’s, the “open letter” he’d fired off to Subcomandante Marcos, the Zapatista insurgent in Chiapas. John’s letter, featured in his The Shape of a Pocket (2001), is a dispatch of great lyrical beauty, about “pockets of resistance,” about hope and disobedience to the neoliberal world order; it’s also about Sardinia and its stones, and about Gramsci, the island’s radical patron saint.

“The least dogmatic of our century’s thinkers about revolution,” John writes Marcos, “was Antonio Gramsci, no? His lack of dogmatism came from a kind of patience. This patience had absolutely nothing to do with indolence or complacency.” “Gramsci believed in hope rather than promises,” says John, “and hope is a long affair.” Gramsci was born in the village of Ales and between six and twelve went to school in the nearby town of Ghilarza, in central Sardinia. When he was four years old, as he was being carried, Antonio fell, crushed his back; a spinal malformation ensued, as well as permanent ill-health.

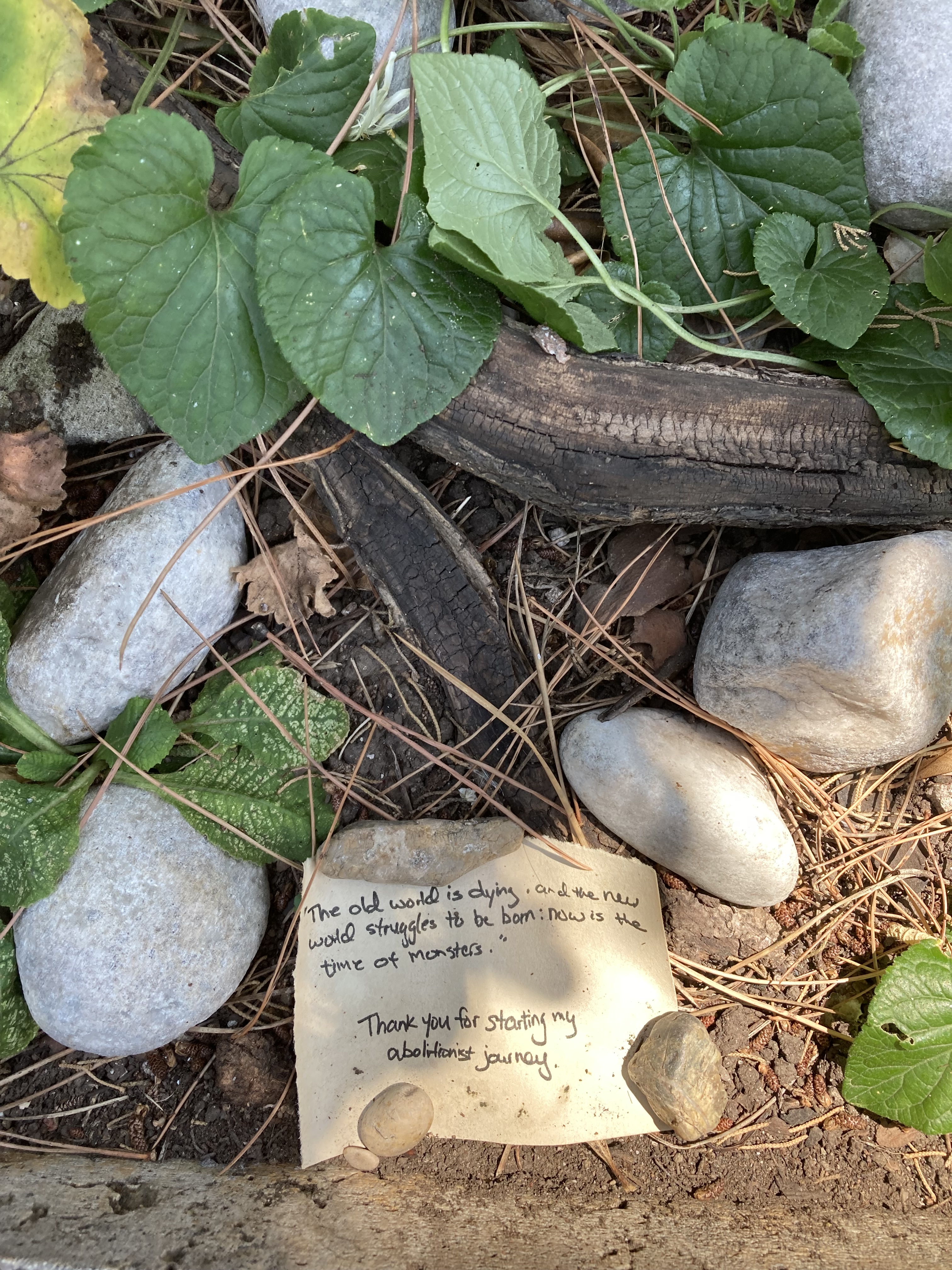

All around Ghilarza are stones, piles of stones, massive granite and limestone, others are smaller rocks gathered and stacked on the poor, arid soil. Stones played a crucial role in Gramsci’s life, John tells us. In Ghilarza, in a museum consecrated to his memory, a glass cabinet has a couple of local stones, about the size of grapefruits, which, every day, as a little boy, Gramsci lifted up and down to strengthen his weak shoulders and deformed back. Similar stones line the front of his grave now, perhaps not uncoincidentally chosen, placed there by well-wishers and followers in the know. I photograph some. They’re also about the size of grapefruits. On a few, words are written, in assorted languages: “Vous avez lutté. Nous luttons. Nous continuons à lutter” [“You struggled. We struggle. We continue to struggle”]. Some stones tack down handwritten notes: “The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born; now is the time of monsters.”

It’s a poetic rendering of a famous Gramsci’s passage, written in June 1930, in a translation often attributed to Slavoj Žižek.“The old world is dying,” says Gramsci, in a more literal version, “and the new cannot be born; and in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.” Gramsci meant a rift between past and future, between a present of great uncertainty, hobbled by morbidity, and a future stymied by monsters lurking around every corner; some, alas, hold office. Still, morbid politics doesn’t reflect a monster’s strength, Gramsci says, so much as belies their weakness, is a condition of their fragility, a crisis of their authority.

Monsters aren’t able to exert their “hegemony” no matter how many Capitols they storm or wars they manufacture. They bully and manipulate, for sure, might even dominate; but they’re rarely leading or in control. What emerges, says Gramsci, is a “form of politics that’s cynical in its immediate manifestation.” Meantime, he says, “the great masses have become detached from their traditional ideologies, no longer believing in what they used to believe previously.” The “physical depression,” Gramsci concludes, might “lead in the long run to a widespread skepticism, and a new ‘arrangement’ will be found.”

In a letter to Tatiana, Gramsci says: “I don’t like throwing stones in the dark; I like to have a concrete interlocutor or adversary.” He was keen to stress the polemical nature of his prison writings, something that would enlarge his “inner life” in a tiny cell. They would constitute a vast intellectual undertaking, we know, begun in earnest in 1928 after the public prosecutor sentenced his brain to stop functioning for twenty-years. Yet incarceration of a sickly body, besieged by uremia, hypertension, tubercular lesions, and gastroenteritis, could never restrain the brilliance of an active, inquisitive mind.

One of this mind’s desires was to overcome the divide between Marxism and everyday experience, between “a philosophy of praxis” and people’s actual consciousness. “The popular element feels,” says Gramsci, “but doesn’t always know or understand.” Demagogues prey on this slippage, stoke up people’s raw feelings and visceral emotions, dislodge them from sound understanding, orchestrate “passive revolutions.” On the other hand, “the intellectual element knows but doesn’t always feel.” Gramsci thinks these are “two extremes” that shouldn’t necessarily be separate. By “popular element,” he meant ordinary people who frequently intellectualize yet don’t function as intellectuals. This isn’t to prioritize one over the other so much as an appeal for knowledge and feeling to mutually interlock, to dialectically fuel each other.

What people feel largely stems from commonsense, Gramsci says, from something immediate in their lives, from gossip and chatter, folklore and faith, vernacular and idiomatic language—from lotteries and tabloid newspapers, Twitter feeds and social and mass media. Gramsci was a steely politico yet generous in his sympathy of popular culture; ambivalent toward it, needless to say, because of its contradictoriness, because of its conservatism, its reactionism. All the same, commonsense could be “part critical and progressive,” he says, something coherent with a “healthy nucleus.”

The latter is the basis of Gramsci’s “good sense,” a commonsense purged of stupidity, relieved of misconception. Good sense is what intellectuals—especially “organic intellectuals”—have to “renovate,” he says, somehow have to “make critical.” To do so, he reckons, “the demands of cultural contact with the ‘simple’ must be continually felt.” I can see John nodding in agreement, hear him saying “yes, yes, yes.” He certainly tried to keep this “organic cohesion” alive, the cultural contact with the simple continually felt throughout his long career of writing and activism. I remember him writing about other figures from Italian popular culture, too, about other artists and intellectuals likewise inspired by Gramsci, and by the cultural contact with the simple. One was filmmaker, poet, and essayist Pier Paolo Pasolini.

John quotes Pasolini in an essay he wrote in 2006 about Pasolini’s 1963 film La Rabbia [Rage]: “For we never have despair without some small hope.” Pasolini also loved Gramsci, even created an affecting poem about him, “The Ashes of Gramsci” (1954), reciting it beside the Sardinian’s tomb (in its old location). It took one to know one: a poem written by a man assassinated by fascists about a man assassinated by fascists.

Here you lie, exiled, with cruel Protestant

neatness, listed among the foreign

dead: Gramsci’s ashes… Between hope

and my ancient distrust, I draw near you, happening by chance on this meagre greenhouse, in the presence of your grave, in the presence of your spirit, afoot, down here among the freeAnd, of this country which would not let you rest,

I feel this an injustice: your mental strain— here among the silences of the dead — what reason — our troubled destiny

Will you ask of me, dead man, unadorned,

that I abandon this hopeless

passion to be in the world?

John watched Pasolini’s film more than forty-years after its making. It had never been publicly shown in Pasolini’s lifetime. In 1962, Italian TV had an idea to ask Pasolini to make a documentary about why everywhere in the world there was fear of war? He made the film but when the TV companies saw it, they balked, got cold feet. John thinks La Rabbia “is a film inspired by a fierce sense of endurance, not anger. Pasolini looks at what is happening with unflinching lucidity.” And his answer to the original question was simple: “The class struggle explains war.”

John says two anonymous voices are spoken in the film, two of Pasolini’s friends, one of whom was likewise John’s friend: the painter Renato Guttuso, whose artwork was chosen to adorn the first postwar membership card of the Italian Communist Party’s (PCI). Guttuso drew particular inspiration for his neo-realist paintings from two sources: Picasso’s Guernica and Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks.

A little while after my cemetery visit, I had another experience with John in Rome, an uncanny one, this time also encountering Renato Guttuso. I was in a branch of the large bookstore chain Feltrinelli, perusing the art section, looking at images rather than texts I could still barely understand—when, all of a sudden, right in front of me, almost beckoning me, finding me rather than I finding it, was John’s book on Renato Guttuso. It had been freshly put into Italian by a small Palermo press, under the stewardship of journalist, essayist, editor, and translator, Maria Nadotti. Maria has been a dedicated champion of John over the years; and through her books and translations has made his work accessible to Italian audiences. In 2019, she produced a wonderfully quirky collection about John’s passion for motorbikes, Sulla motocicletta, with a translated piece from yours truly, on “Spinoza’s Motorcycle,” my riff on John’s riff on the Dutch philosopher from Bento’s Sketchbook.

Maria’s latest translation, like Sulla motocicletta, is a lovely little work of art in its own right, produced by an independent press that appears less concerned with bottom-line dictates than with creating an object of intense beauty, a labor of love with artisanal integrity, never intending it to be anything commercial. A few years ago, I’d sent Maria an email, congratulating her on Sulla motocicletta, receiving a response: “I miss John enormously,” she’d said. “The only way I find to compensate for his physical absence is to work on his texts, words, ideas, and to keep ‘conspiring’.” And so here was Maria again conspiring with John, resuscitating a book over half-a-century old, with a publisher based in Guttuso’s native Sicily.

What’s fascinating about Guttuso is that it was, in fact, John’s first book, from 1957. And yet, oddly, it was a ninety-page text written in English that never appeared in English, going straight into German under the auspices of Dresden’s Verlag der Kunst, edited by John’s friend Erhard Frommhold. (John says he was always indebted to Frommhold; it was he who’d given John the belief that he could become not only a writer but a writer of books.) Maria had somehow managed to unearth John’s original dog-eared typescript from his British Library archives, with handwritten annotations and missing pages, and set herself the task of reconstructing it, of recreating it in Italian. How thrilled John would have been had he seen it!

At one point in her introduction, Maria’s discusses the link between John and Elizabeth David’s Italian Food, a book of Guttuso’s generation, and how Guttuso had been commissioned to do its illustrations. Apparently, John had a copy of Italian Food when he lived in London, cooking from it often at his flat at 4 Nutley Ter in South Hampstead, without ever realizing that inside was Guttuso’s artwork. One of the book’s most arresting images is of a lone workman, dressed in simple jacket and stripped shirt, eating a pasta lunch, literally shoveling it into his mouth ravenously; a tumbler of red wine lies beside him. Guttuso captures the intense, quasi-religious devotion of a man to an everyday meal, savoring it as if it were his last supper. Elizabeth David quickly realized that “the dangerously blazing vitality” Guttuso invested in the commissioned artwork, became “an integral part of my book.”

A similar image of the pasta-lunching laborer, perhaps the same laborer—the lithograph’s master copy—can be seen tacked to the wall of Guttuso’s studio at Rome’s Villa Massimo, in a photo taken of a wistful painter in 1956. Nearby are Guttuso’s cult heroes, similarly tacked to the studio’s wall: a poster of Picasso’s Guernica, and below it, a couple of tatty photographs of Antonio Gramsci. John writes about Guttuso’s “inherent connection between art and politics: politics being used in the broadest sense of the word to describe that struggle of social forces which underlies any particular social order.” He says that “Guttuso reacted strongly against the neo-classicism being encouraged by the fascists.” On the other flank, his adherence to the Communist Party and avant-garde modernist art, to so-called picassismo, also meant a sometimes fraught relationship to the Party, with its espousal of Socialist Realism, mimicking Gramsci’s own fraught relationship to the Party he’d helped found. The pair’s “cultural politics” was mistrusted by those who saw Marxism as the iron laws of economism.

When Gramsci died, Guttuso would have been a young man of twenty-six. We can assume they never met. But Guttuso would have absolutely encountered first-hand Gramsci’s one-time friend and co-founder of Ordine Nuovo newspaper, Palmiro Togliatti, the PCI’s Secretary, formerly Gramsci’s closest political ally and fellow Party brainchild. (Togliatti and Gramsci fell out not long after the former took the PCI’s helm in 1927, each taking opposing stances toward Stalin’s Marxist-Leninist orthodoxy.) John points out that Guttuso’s own commitment to the Party and to the working-classes was no less resolute because of his expressionist art. “It is the everyday life of Italy,” he writes, “the carrying in of the weight of the harvest, the determination of the miner, the setting up of the telegraph poles throughout the landscape, the terracing of the hills, that Guttuso celebrates.”

Maybe this reflects what John says defines Guttuso’s art: “that it is outstanding because it so obviously implies an ambitious and compelling sense of obligation” (emphasis added). “One can only grow through obligations,” repeats John, in a phrase he attributes to Antoine Saint-Exupéry. “Obligation” is the operative word, a sense of service and commitment, duty-bound, an acknowledgement of a necessary interaction between art and life. John goes to pains to underscore this notion of obligation, and I wonder now, after drafting these words, after working through my thoughts about John, kickstarted by my re-reading of White Bird—whether that night at the bar in Monti, whether it was obligation I felt, an obligation to keep John’s spirit alive, to continue to struggle artistically and creatively as he had struggled, to “conspire” with him as Maria Nadotti had said, and to continue to keep the Red Flag flying; to be obligated to Gramsci, too, a sentiment reinforced by those stones I’d seen at his graveside, stones about the size of grapefruits he’d exercised with as a small boy.

So a strange sense of obligation had come over me at the cemetery as well, compelling me to return there, where I spoke to Tatiana, a good omen maybe, the coordinator of the Visitor’s Center. She’d told me that they were always looking for responsible volunteers to work here, young as well as older people. The cemetery is a private institution, she said, receives no public funding, and survives exclusively off donations and volunteer services. And it is still active, welcoming visitors at the same time as it respects families of the deceased, holding funerals and burials, tending gravestones, ensuring the general upkeep of a magnificent verdant landscape.

In my book Marx, Dead and Alive, I wrote about Marx in London’s Highgate Cemetery, shocked at the desecration of his tomb by vandals; they’d daubed it with red paint and walloped it with a lump hammer; I’d been attracted by the specialness of Highgate, by its peacefulness and tranquility, and dismayed at the demented violence shown toward it and Marx. I guess I felt something similar here in Rome now, felt an allure and fascination, and maybe, in these right-shifting political times, also had a similar concern for Gramsci’s fate, that he was safe, because I decided, there and then, to offer my services as a volunteer at the cemetery if they wanted me.

A few days on, I met Yvonne, the cemetery’s Director, an American who’s lived in Italy for twenty-five years and has a PhD in Art History. She wondered why I wanted to volunteer. I said I had time and wanted to be near Gramsci. Yvonne feels strongly about the contemplative atmosphere of the cemetery, about its slow, “unplugged” ambience. Visitors need to be sensitive, she’d said, that the cemetery is a site of peace, reflection, and remembrance, not another tourist spectacle for Instagram selfies or posting comic videos. She wants to nudge visitors off their cameras and iPhones, get them into “live” experience.

After my “interview,” Yvonne welcomed me to the cemetery, happy to have me onboard, but suggested I continue to learn Italian. Then she admitted that she had used Gramsci in her own studies on the conservation of historic sites in Orte, a town fifty miles north of Rome. Gramsci, she said, was for her the cemetery’s most important person, its special VIP. As I exited, excited about my new part-time role, walking up via Caio Cestio back into the bustle of the city again, I thought to myself that, henceforth, I’m not only going to try to keep Gramsci’s spirit alive—now, incredibly, I’m also going to keep an eye on him dead.

*Coda: Maria Nadotti and John visited Rome’s Non-Catholic Cemetery together on October 12, 2014. “John sat a long while,” Maria told me recently, “beside the grave of Gramsci, then drew a stone in a sketchbook. Finally he put the drawing on the grave among the other stones.”

Maria took three photographs of John. “It was a very intense private moment,” she said, “but I believe that John would be happy to share it and make it public.”

I am very grateful to her for letting me post these images: