Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Imagine this scenario. On 11 September 1973, the reactionary sections of the Chilean army, led by General Augusto Pinochet and given a green light by the U.S. government, did not leave their barracks. President Salvador Allende, who led the Popular Unity government, went to his office in La Moneda in Santiago to announce a plebiscite on his government and to ask for the resignation of several senior generals. Then, Allende continued his fight to bring down inflation and to realise his government’s programme to advance the socialist agenda in Chile.

Until the moment when the Chilean Army descended upon La Moneda in 1973, Allende and the Popular Unity government were in a pitched fight to defend Chile’s sovereignty, particularly over its copper resources and its land as they sought to raise sufficient funds to eradicate hunger and illiteracy and to produce innovative means to deliver health care and housing. In the Popular Unity programme (1970), the Allende government founded its charter:

The social aspirations of the Chilean people are legitimate and possible to satisfy. They want, for example, dignified housing without readjustments that exhaust their income; schools and universities for their children; sufficient wages; an end once and for all to high prices; stable work; timely medical attention; public lighting; sewers; potable water; paved streets and sidewalks; a just and operable social security system without privileges and without starvation-level pensions; telephones; police; children’s playgrounds; recreation areas; and popular vacationing and sea resorts.

The satisfaction of these just desires of the people—which, in truth, are rights that society must recognise—will be a preoccupation of high priority for the popular government.

Realising the ‘just desires of the people’—a laudable objective—was possible amidst the public’s optimism for the Popular Unity government. Allende’s administration adopted a model that decentralised the government and mobilised the people to attain their own ‘just desires’. Had this model not been interrupted, the depositors in the government’s social security institutions would have remained on directive councils with oversight of these funds. Organisations of slum dwellers would have continued to inspect the operations of the housing department tasked with building quality housing for the working class. Old democratic structures would have continued to strengthen as the government used new technologies (such as Project Cybersyn) to create a distributed decision system. ‘It is not only about these examples’, the programme noted, ‘but about a new understanding in which the people participate in state institutions in a real and efficient way’.

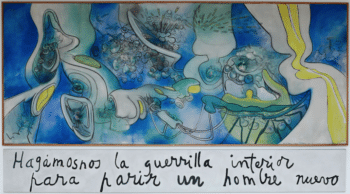

Roberto Matta (Chile), Hagámosnos la guerrilla interior para parir un hombre nuevo (‘Let’s Fight the Guerilla War Within Ourselves to Give Birth to a New Man’), 1970. Oil on canvas, 259 x 491 cm.

As Chile’s people, led by the Popular Unity government, took control over their economic and political lives and worked hard to improve their social and cultural worlds, they sent a flare into the sky announcing the great possibilities of socialism. Their advances mirrored those that had been attained in several other projects, such as in Cuba, and boosted the confidence of people across the Third World to test their own possibilities. The eradication of poverty and the creation of housing for every family was an inspiration for Latin America. Had the Popular Unity project not been cut short, it very well might have encouraged other left projects to demand the satisfaction of just desires in a world where it was possible to attain them. No longer would we live in a world of scarcity, which impedes the realisation of these desires. No Chicago Boys would have arrived with their noxious neoliberal agenda to experiment in the laboratory of a military regime. Popular mobilisations would have exposed the illegitimate desire of the capitalist class to impose austerity on the people in the name of economic growth. As Allende’s government expanded its agenda, driven by a decentralised government and by popular mobilisation, the ‘just desires’ of the people might have eclipsed the narrow greed of capitalism.

If there had been no coup in Chile, there might not have been coups in Peru (1975) and Argentina (1976). Without these coups, perhaps the military dictatorships in Bolivia, Brazil, and Paraguay would have withdrawn in the face of popular agitation, inspired by Chile’s example. Perhaps, in this context, the close relationship between Chile’s Salvador Allende and Cuba’s Fidel Castro would have broken Washington’s illegal blockade of revolutionary Cuba. Perhaps the promises made at the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) meeting in Santiago in 1972 might have been realised, among them the enactment of a robust New International Economic Order (NIEO) in 1974 that would have set aside the imperial privileges of the Dollar-Wall Street complex and its attendant agencies, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. Perhaps the just economic order that was being put in place in Chile would have been expanded to the world.

But the coup did happen. The military dictatorship killed, disappeared, and sent into exile hundreds of thousands of people, setting in motion a dynamic of repression that has been difficult for Chile to reverse despite the return to democracy in 1990. From being a laboratory for socialism, Chile—under the tight grip of the military—became a laboratory for neoliberalism. Despite its relatively small population of roughly ten million (a tenth of the size of Brazil’s population), the coup in Chile in 1973 had a global impact. At that time, the coup was not just seen as a coup against the Popular Unity government of Salvador Allende, but as a coup against the Third World.

That is precisely the theme of our latest dossier, The Coup Against the Third World: Chile, 1973, produced in collaboration with Instituto de Ciencias Alejandro Lipschutz Centro de Pensamiento e Investigación Social y Política(ICAL). ‘The coup against Allende’s government’, we write, ‘took place not only against its own policy of the nationalisation of copper, but also because Allende had offered leadership and an example to other developing countries that sought to implement the NIEO principles’. At the third session of UNCTAD in Santiago (1972), Allende said that the mission of the conference was to replace ‘an obsolete and radically unjust economic and trade order with an equitable one that is based on a new concept of man and human dignity and to reformulate an international division of labour that is intolerable for the less advanced countries and that obstructs their progress while favouring only the affluent nations’. This was exactly the dynamic that was derailed by the coup in Chile as well as by other manoeuvres of the imperialist bloc. Instead of promoting an order ‘based on a new concept of man and human dignity’, these manoeuvres resulted in the murder of hundreds of thousands of people’s advocates (among them leftists, trade unionists, peasant leaders, environmental justice campaigners, and women’s rights activists) and prolonged the destiny of hunger and illiteracy, poor housing and medical care, and the general orientation of a culture of despair and toxicity.

Please read our dossier and share it. These dossiers—produced once a month—are a product of collaboration and hard work, a synthesis of how we, as an institute rooted in popular movements, see key events of our history. The art for this dossier comes from the Salvador Allende Solidarity Museum, which preserved art from the Popular Unity period and from the struggle against the coup. We are grateful to them, and to ICAL, for our collaborations based on solidarity and against the neoliberal ethic of parochial greed.

Please read our dossier and share it. These dossiers—produced once a month—are a product of collaboration and hard work, a synthesis of how we, as an institute rooted in popular movements, see key events of our history. The art for this dossier comes from the Salvador Allende Solidarity Museum, which preserved art from the Popular Unity period and from the struggle against the coup. We are grateful to them, and to ICAL, for our collaborations based on solidarity and against the neoliberal ethic of parochial greed.

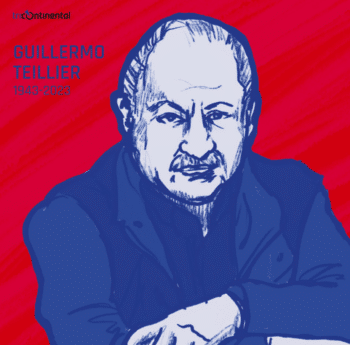

Two weeks before the fiftieth anniversary of the coup in Chile, Guillermo Teillier, the president of the Communist Party of Chile (PC), died. At his funeral, the party’s general secretary Lautaro Carmona Soto described how Teillier—with the coup’s cordite still in the air—went to work in Valdivia to protect and then build the party as part of the broader resistance to the coup regime. In 1974, Teillier was arrested in Santiago and subsequently held and tortured for two years in the Academia de Guerra Aérea. For another year and a half, Tellier was held in concentration camps in Ritoque, Puchuncaví, and Tres Álamos. Released in 1976, he went into hiding and continued to build the party back to its fighting strength, joined the following year by PC leader Gladys Marín. This was dangerous work, made even more dangerous when Tellier took over as the leader of the party’s military commission, which managed the aid sent from Cuba to Chile and oversaw the creation and operations of the Manuel Rodríquez Patriotic Front (FPMR), the PC’s armed wing. Though attempts to assassinate Pinochet failed, broader work to build the movement for democracy succeeded. It is the bravery and sacrifice of people such as Tellier, Marín, and countless—and often nameless—others, that brought the dictatorship of Pinochet and the Chicago Boys to an end in 1990.

The 1973 coup in Chile destroyed lives and suspended a process of great promise. Today, that promise must be revived.

Warmly,

Vijay