I want to plunge into animality to draw from it new vigor.

— Gramsci, New Year’s Day, 1916

One of the central “living” attractions of Testaccio’s Non-Catholic cemetery is its stray cats, a colony of twenty-five or so semi-feral moggies. We know from old paintings of the nearby Pyramid, especially those by the Roman artist Bartolomeo Pinelli, that cats have freely roamed the area for over 150 years. Nowadays, tourists and locals alike come to see the cemetery’s gatti, longtime beneficiaries of well-wisher donations and skilled volunteer caregivers, cat men and women who regularly nourish and tend the cat colony’s veterinarian needs. (The most famous of the cemetery’s felines is the late “Romeo,” a three-legged tabby who passed away in 2006, laid to rest in his own mini-tomb not far from Gramsci’s.)

Many cats have their favorite spots where they’re often seen sniffing the scent of late departed ones, their bones and ashes. Gramsci, too, has a familiar prowler and protector, a big white and gray with an apparent penchant for revolutionary communism. He’s always wandering about the PCI founder’s tomb, oftentimes lying across his casket, or else upright on it, head aloft, proudly standing to attention, on the lookout for reactionary trouble; a mini militia of one keeping a left paw out for old Gramsci. Perhaps we might label this loyal moggie, “The General,” after Engels’s old sobriquet, and our General knows intuitively, like most animals, where his bread is buttered—who is friend or foe. Gramsci, of course, was a dear friend, an animal lover whose humanist life and thought forever embraced non-human comradery.

Prison Notebooks sets the tone with “Animality and Industrialism,” Gramsci’s original work-in-progress header for the section he’d eventually label “Americanism and Fordism.” No metaphor intended. The history of industrialism, Gramsci says, “has always been a continuing struggle against the element of ‘animality’ in man.” “It has been,” he adds, “an interrupted, often painful and bloody process of subjugating natural (i.e. animal and primitive) instincts to new, more complex and rigid norms and habits of order, exactitude and precision which are a necessary consequence of industrial development.” Animality, we might say, is a more instinctive life spirit, something looser, more rambunctious and libertine, potentially more subversive, unsettling for the soberer necessities of workforce obediency. As Gramsci puts it,

the exaltation of passion cannot be reconciled with the timed movements of productive motions connected with the most perfected automatism.

That’s why the bourgeoisie must constantly wage war against animality, why its “puritanical struggles” get embedded in the state. Gramsci reckons it’s another historical instance of how “changes in the modes of existence and modes of life have taken place through brute coercion, that is to say through the domination of one group over all the productive forces of society.” New forms of productive organization beget new kinds of “education,” new forms of coercion and consent to condition people to industry’s developmental needs. Henry Ford was a classic pioneer, patrolling not only how his workforce labored on the assembly line (deploying F.W. Taylor’s “scientific management” techniques), but also how workers led their private lives, monitoring how they spent their wages, advocating a “morality” more appropriate for the “true” America—at least for a certain stratum of its populace.

With his infamous phrase “trained gorilla,” Taylor threw back in the faces of workers the whole idea of animality. Gramsci calls it “brutally cynical.” Yet, in truth, he also knew that such repetitive, soul-sapping activity—indeed any kind of grinding, contentless work in whatever division of labor…blue-collar, white-collar, no collar or otherwise—is a venture no gorilla would ever likely deign to undertake. “I prefer not to,” they’d probably say, if they could talk human language. Or else they’d become, as John Berger said in his well-known essay “Why Look at Animals?” (1977), like an animal in a zoo, “lethargic and dull. (As frequent as the calls of animals in a zoo are the cries of children demanding: Where is he? Why doesn’t he move? ‘Is he dead?’).” (Berger also reminds us how most modern techniques of social conditioning were first established with animal experiments.)

Gramsci defends animality against the “moral order” of social conditioning—in both its capitalist and communist guises. In Prison Notebooks, he expressed disagreement with a certain “Leone Davidovi,” aka Leon Trotsky, who’d been pro the rationalization and militarization of work under Soviet communism: “every worker feels himself a soldier of labor,” Trotsky said, “who cannot dispose of himself freely; if the order is given…he must carry it out; if he does not carry it out, he will be a deserter who is punished.” Gramsci says this military model was “a pernicious prejudice and the militarization of labor a failure.” The fact that the worker no longer has to think about their work and gets no immediate satisfaction from carrying out its repetitive tasks, means, Gramsci says, that they have opportunities to think about other things, perhaps even leading to “a train of thought that is far from conformist.”

Eight months before the October Revolution, a youthful Gramsci had already mulled over how bourgeois discipline ought to differ from socialist discipline—how the former’s mechanical and authoritarian paradigms are at variance with socialist paradigms. Bourgeois discipline, he wrote in La città futura, “keeps the bourgeois aggregation firmly together. Discipline must be met with discipline.” Everybody obeys in the bourgeois state. Its model, Gramsci says, is English colonialism in India, ironized in Rudyard Kipling’s short story “Her Majesty’s Servants” (from The Jungle Book): horses obey the soldiers riding them, soldiers obey sergeants, sergeants obey lieutenants, lieutenants captains, captains majors, majors colonels, colonels brigadiers, brigadiers generals, and generals the Viceroy who in turn obeys the Queen. Everybody moves in unison, has their role strictly defined, drilled into them, each and all obeying one another in a tight, rigid hierarchy, extendedly reproduced. “Thus it is done,” says Kipling,

because you cannot do likewise, you are our subjects.

Socialist discipline, by contrast, “is autonomous and spontaneous,” says Gramsci. “Whoever is a socialist or wants to become one does not obey; they command themselves; they impose a rule of life on their impulses, on their disorderly aspirations.” The discipline imposed on citizens by the bourgeois state turns them into subjects. Socialist discipline is counter wise, turning subjects into citizens: “a citizen who is now rebellious, precisely because they have become conscious of their personality and feel it is shackled and cannot freely express itself in the world.” Maybe this is what Gramsci meant by animality: something unshackled, not caged in a zoo.

***

In a letter to Delio from 1936, Gramsci is a little stern, warning his young son of the dangers of “anthropomorphism,” of attributing human traits to animals. In this case, it is elephants Delio has referred his father to. Delio had had the bright idea that elephants might one day evolve and walk on two legs, becoming, like humans, capable of conquering the forces of nature. Yet papa reverses the anthropomorphic hypothesis of Delio’s, querying “why should the elephant have evolved like man? Who knows whether some wise old elephant or some whimsical young little elephant doesn’t from his point of view think up hypotheses as to why man has not become a proboscidiform creature.” Then, a few sentences on, maybe wary that he’s getting heavy with his son, Gramsci softens his tone, and through animals tries to kindle his son’s vivid imagination (rather than dampen it): “in the courtyard,” he tells Delio,

I always see two pairs of blackbirds and the cats who crouch in ambush, ready to pounce; but it doesn’t seem that the blackbirds worry about it and their flitting about is always gay and elegant. I embrace you. Papa.

Animals help Gramsci connect with his long-lost son. Giuliano is too young to really write to his father, so dad’s focus is on Delio, often desperately attempting to embrace a child he was conscious of losing touch of—going to school, reading books, growing up, becoming Russian, speaking Russian—all of it, slipping away from Gramsci’s grasp; and his letters reveal the frustration and desperation of a father who wanted to know, who tried to cling on. “In truth,” he told wife Giulia (letter dated December 14, 1931),

I’m unable psychologically to establish a rapport with them because concretely I know nothing about their life and their development.

He tries very hard in many letters, oftentimes too hard, talking to a child as if he were an adult, only underscoring the growing distance—the emotional, temporal, and spatial distance—from him and his family. Gramsci didn’t always know it, but Giulia herself was frequently absent from childrearing, institutionalized with periodic mental breakdowns and bouts of depression, leaving Gramsci’s sons in the care of his other sister-in-law, Eugenia. Once close, over the years mutual resentment grew between Eugenia and brother-in-law Antonio.

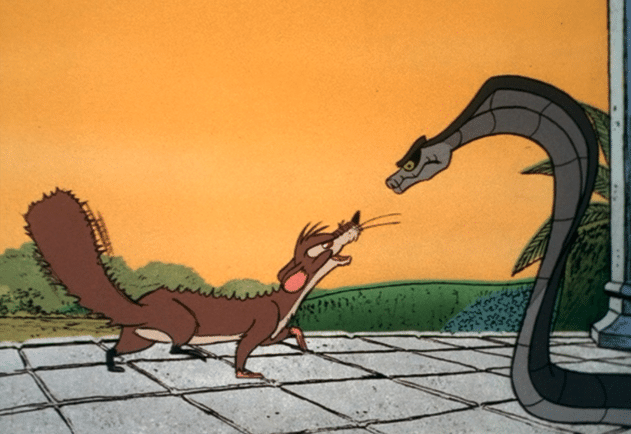

“When I was a boy,” Gramsci again writes Delio (February 22, 1932), “I raised many birds as well as other animals: falcons, barn owls, cuckoos, magpies, crows, goldfinches, canaries, chaffinches, larks, etc. I raised a small snake, a weasel, a hedgehog, and some turtles…I amused myself by bringing live snakes into the courtyard to see how the hedgehog would hunt them.” Little wonder, then, does Gramsci recommend to his son Kipling’s story about Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, the intrepid snake-sleighing mongoose from The Jungle Book. Rikki-Tikki-Tavi is one of Kipling’s most endearing (and enduring) characters, a featherweight who takes out heavyweights, huge Cobras and Black Mambas. His “business in life,” Kipling says, “was to fight and eat snakes.” A little underdog—or undergoose—who tackles bigger, more powerful foe, brandishing agility and cunning. Perhaps it’s not too difficult to see why Gramsci might be so charmed by the tale.

Kipling, peculiarly, appears as one of Gramsci’s favorite authors. The English novelist, short story writer, poet, and journalist crops up often in Gramsci’s works—in his letters, Prison Notebooks, and cultural essays—sometimes in surprising contexts, reappropriated in unexpected, imaginative ways. (In prison, Gramsci even translated Kipling’s most famous poem “If—,” published in 1910, once Britain’s best loved verse.) Although he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907, when Gramsci read him Kipling was scarcely known in Italy. Thus it’s not entirely clear how Gramsci got wind of the colonial scribe, all the more given his right-leaning, anti-communist politics, and racist language—notwithstanding an enormous sensitivity to teeming, poor, Indian street life. (Kipling did make the Italian news in May 1917, when, at the behest of the Daily Telegraph, he visited the Italian front to write a series of first-hand dispatches, later published in pamphlet form as The War in the Mountains: Impressions from the Italian Front; Gramsci would have likely known about such a trip and read Kipling’s five articles in Risorgimento Press’s Italian paperback edition.)

In Quaderno No.3, Gramsci makes a comment on Kipling that reads like a note to self: “Could Kipling’s work serve to criticize a certain society that claims to be something without developing the corresponding civic morality within itself, indeed having a mode of being contradictory with the goals that it verbally sets itself.” “Kipling’s morality is imperialistic,” Gramsci says,

only when it is closely linked to a very specific historical reality: but images of powerful immediacy can be extracted from it for every social group that fights for political power.

We know from Gramsci’s letters that he’d read Kipling in French. (Kipling himself was an ardent Francophile.) Ironically, Kipling’s poetry was admired by interwar Soviet avant-garde writers, so one might surmise that Gramsci picked up on Kipling through those channels; but that doesn’t quite stack up, because Gramsci had already referenced The Jungle Book well before the Bolsheviks had seized power. In fact, Gramsci sometimes signed off his Avanti! and Il Grido del Popolo [The Cry of the People] articles with the pseudonym “Raksha,” after the formidable she-wolf protector of Mowgli, The Jungle Book’s “man-cub,” whom Raksha adopts as part of her wolf family, fending off the notorious tiger Shere Khan when he tries to eat baby Mowgli. Raksha becomes a kind of animal organic intellectual, clearly inspirational for Gramsci.

Meanwhile, Kipling’s darker tales, like “The Strange Ride of Morrowbie Jukes” (1885), spoke to Gramsci on a gut level. In the story, men are burned at the stake and then tossed down a deep sandy pit, left for dead but still somehow living; a dwelling place of the dead, says Kipling, “for the dead who do not die but may not live.” An old Indian adage cues the text: “alive or dead—there is no other way.” In prison, in confinement, teeth falling out and health rapidly declining, Gramsci begged to differ, as apparently does Kipling, prefiguring Beckett’s gloomy oeuvre by half a century. “The Strange Ride,” Gramsci tells Tatiana (December 9, 1926), “immediately leaped to my mind, so much that I felt I was living it.” And, again, ten-days on (December 19, 1926), he repeats the message: “you must believe me when I say that my reference to Kipling’s short story was not an exaggeration.” (Remember, too, how Gramsci’s catchphrase that “the world is great and terrible” was borrowed from the Tibetan Buddhist lama who’d starred in Kipling’s Kim.)

Gramsci is keen to share with Delio Kipling’s cheerier tales. The Jungle Book’s mongoose “is eaten up from nose to tail with curiosity. The motto of all the mongoose family is ‘Run and find out’; and Rikki-Tikki-Tavi was a true mongoose.” “I think you know the story of Kim,” Gramsci writes his son (February 22, 1932); “but do you know the tales in The Jungle Book and especially the one about the white seal and about Rikki-Tikki-Tavi?” The latter story’s climatic scene is Rikki-Tikki’s showdown with the cobra Nagaina, who, along with husband Nag, had terrorized Teddy’s household, the boy who’d befriended Rikki-Tikki. (Rikki-Tikki had already seen off Nag.) “Now I have Nagaina to settle with,” the mongoose says, “and she will be worse than five Nags, and there’s no knowing when the eggs she spoke of will hatch. Goodness!” All’s well that ends well, though.

“The White Seal” features another unlikely hero from The Jungle Book, only his domain is the chilly high sea; a cub called Kotick who grows up into a mighty white seal whose sole purpose in life is “to find a quiet island with good firm beaches for seals to live on, where men could not get at them.” Other seals made fun of Kotick, with his crazy ideas of imaginary islands. Everywhere he went, seals told Kotick the same thing: seals had come to islands once upon a time, “but men had killed them all off.” Still, one day, Kotick vowed he’d lead the seal people to a quiet place. At the story’s close, he roared to the seals:

I’ve found you the island where you’ll be safe, but unless your heads are dragged off your silly necks you won’t believe.

Gramsci’s most famous animal story is now a children’s text frequently read by teachers throughout Italy’s elementary schools: Il topo e la montagna [The Mouse and the Mountain]. In a letter dated June 1, 1931, Gramsci says to his wife, “I would like to tell Delio a tale from my town that seems interesting. I’ll summarize it for him and Giuliano. A child is sleeping,” Gramsci begins. There’s a mug of milk ready for him when he wakes up. But a mouse sneaks in and drinks the milk. In the morning, when the child opens his eyes, seeing no milk, he starts screaming. Then his mother screams.

The mouse realizes what he’s done and, feeling guilty, runs to the goat to find milk. The goat will give the mouse milk if he can get grass for the goat to eat. The mouse goes into the fields looking for grass but, lacking water, the fields are all parched. The mouse goes in search of a water fountain. The fountain, however, has been ruined by war and the water is seeping out into the ground. The mouse goes to the mason, hoping he can repair the fountain, yet the mason lacks stones. The mouse goes to the mountain and then, says Gramsci,

there’s a sublime dialogue between the mouse and the mountain, which has been deforested by speculators and reveals everywhere its bones stripped of earth.

The mouse recounts the entire story to the mountain and promises that when the child grows up, he’ll replant trees on the mountain’s plains. So the mountain gives the mouse stones, and the child eventually has so much milk that he can bathe in it. And when the child grows up, he does as the mouse had promised and plants trees, and everything changes:

the mountain’s bones disappear under new humus, atmospheric precipitation once more becomes regular because the trees absorb the vapors and prevent torrents from devastating the plain. In short, the mouse conceives of a true and proper five-year plan. Dearest Giulia, I really want you to tell them this story and then let me know the children’s impressions. I embrace you tenderly.

***

Gramsci felt “very poignant regret” about being an absent father, deprived of the chance of watching his kids mature, of sharing in the development of their personalities. Perhaps he felt this regret even more than his inability to be a political man of action, something he strived to do, vowed, since his student days in Turin. Some Gramsci scholars have pointed out this dialectic tugging away inside him, the perpetual torment between a political man and a family man, poignantly expressed in one of his staple pieces of reading—“Canto X” of Dante’s Inferno, the first book of The Divine Comedy, which Gramsci had studied off and on for more than twenty-years, reading and rereading it, able to recite it from memory.

The late Frank Rosengarten, who edited and introduced Columbia University Press’s wonderful two-volumes of Gramsci’s Letters from Prison (the only complete English edition), highlights Gramsci’s “little discovery” with Canto X, where “two dramas” unfold: the political drama, enacted by the character Farinata, and the personal drama of Cavalcante. Gramsci wrote Tatiana on August 26, 1929 that “I’ve made a little discovery about this canto by Dante that I believe is interesting and in part corrects Croce’s thesis on The Divine Comedy, which is too absolute.” Rosengarten says Gramsci was original and correct in his belief that everyone had overlooked the plight of Cavalcante, who, in hell, was anguished by the uncertain fate of his son, Guido.

Cavalcante’s cameo plays second fiddle to the seemingly more important political tragedy of Farinata. Gramsci suggests that in Canto X Dante wasn’t so much concerned with politics as with the sufferings of a heart-stricken father. Canto X becomes personal as well as political for Gramsci, the double commitment and tussle of a man who fought for his socialist ideals and a husband and father tormented by the forced separation from his wife and sons: “Weeping, he said to me: ‘If through this blind/ Prison thou goest by loftiness of genius,/ Where is my son? and why is he not with thee?’” In a sense, then, we might conclude that animality speaks to both flanks of Gramsci’s personality, to the libertarian thinker and to the father storyteller, protective of his offspring, displaying real gifts for narrating fables in his letters, for telling stories about animals.

That libertarian also knew another animal fable, one we’ve yet to mention, a strictly adult affair about realpolitik, about Machiavelli’s Centaur—the half-human, half-animal figure, with its dual powers. “You must understand,” says Gramsci, quoting Machiavelli’s The Prince, “that there are two ways of fighting: by the law and by force. The first way is natural to men, the second to beasts.” Any successful movement, Gramsci believes, again following Machiavelli, must be able to assume both the nature of humans and beasts, the nature of the fox as well as that of the lion; “for while the latter cannot escape the traps laid for him, the former cannot defend himself against the wolves”; the strategic ferocity of the lion and the tactical cunning of the fox, a blend of force and consent, of coercion and persuasion in the struggle for a popular Left hegemony.

Machiavelli, of course, says nothing about mongooses; yet for Gramsci this sort of animality meant fatherly urging, encouraging his sons to think critically while always keeping their imaginations alive, getting “eaten up from nose to tail,” like Kipling’s Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, “with curiosity,” sniffing about for adventure, always being inquisitive, wanting to know why, forever “running and finding out.” A little lesson in everyday life that one—not only for kids and other animals, but for grown-up humans, too.

***

The General is out and about on patrol today, on duty again, pacing around Gramsci, doing his drills, his rounds of surveillance, ensuring that all’s well. It’s a lovely, bright, autumn morning, cool relief from the summer’s heat. A sweet light strikes upon Gramsci’s tomb, as it so often does. The General—let’s relabel him “Gramsci’s cat”—seems as content as ever as another cemetery day begins its quiet course. Perhaps he won’t mind if I cite to him, gently under my breath, a few lines from Dante’s Canto X, as Gramsci might have liked:

Now onward goes, along a narrow path/ Between the torments and the city wall,/ My master, and I follow at his back.

I sit on Gramsci’s bench and watch Gramsci’s cat strut back and forth along the narrow path, between his master and the Aurelian city wall, and remember that the drama of Canto X actually takes place in a cemetery. “The people who are lying in these tombs,/ Might they be seen?” Suddenly, Gramsci’s cat leaps onto my lap, rubbing his head against my chest. If you sit here long enough, calmly enough, and are respectful enough toward Gramsci, he will surely do the same for you. I begin to stroke him, ruffling my hands through his thick fur. “Be pleased to stay thy footsteps in this place,” we say to each other, unspokenly. I’m communing with a cat and a dead Marxist in soft Roman sunshine, trying to keep alive our conversation, and thinking that maybe I’m beginning to get what animality might really mean.