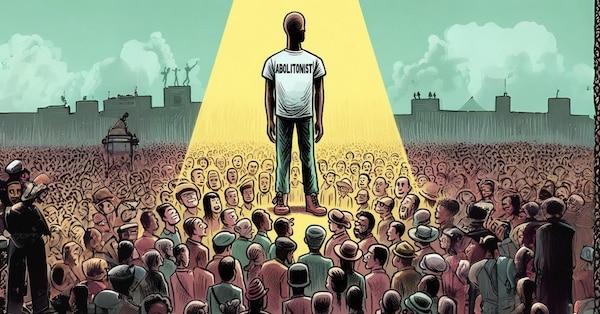

Politics can change and evolve. Considering the dialectical nature of embodied knowledge or ‘lived experience’ and politics, it is imperative to acknowledge that these processes inherently demand change and evolution. In other words, what one strongly believes can be reconsidered and analyzed alongside objective material analysis, as both are theoretically in a constant state of development. Since 2020, there has been a gradual realization about the limitations of various strategies, ideologies, and political approaches, particularly in the context of using “abolition” as a catch-all umbrella.

To grasp the U.S. state in its specific and complex dimensions, one needs to recognize the conditions of colonized people as arising from a ‘carceral relationship with the state’; within this context, abolition as a political stance appeared to be a natural and fitting response. Despite occasional questions or perceived inconsistencies in certain proclamations, the political principles of abolition seemed valid enough to warrant organizing around. Our engagement with “abolition” manifested through actions such as joining coalitions with abolitionists, initiating a book club to explore unanswered questions, and advocating for the incorporation of abolition frameworks in various organizing efforts.

However, as we delved into a more profound understanding of anti-imperialist and Black internationalist frameworks, particularly through direct involvement with Africans in locations like Cuba or Nicaragua, it became evident that the application of an abolition framework fell short in comprehensively analyzing the interconnected conditions faced by colonized people. Acknowledging our own gradual process of reevaluating abolition, it’s clear that certain conclusions wouldn’t have been reached without a serious consideration of organizing against the primary contradiction—imperialism. This deliberate focus compels an in-depth exploration of the conditions in the Third World, prompting an examination of the imperialist history and structures responsible for shaping those conditions.

As we delved into a more principled grasp of scientific socialism and gained ideological clarity through study and organizing, the constraints of “abolition” became apparent. Domestically, these limitations are observable in the continual redefinition and individualization of ‘abolition,’ adapting ad hoc as needed, influenced by the motivations of those employing it. This term has been embraced by activists and academics alike, resulting in varying connotations within different contexts. This ultimately prompts self-proclaimed abolitionists to assert that “abolition is a practice.” In examining this perspective on abolition, a noticeable trend emerges—the reluctance to systematically map out the practice in a principled and scientific manner. Notably, there is a deliberate avoidance of engaging in discussions about socialism and the concept of a socialist state within the framework of abolition.

This raises the question of why abolition, portrayed as a practice, is articulated separately from, or even in lieu of, the endeavor to construct socialism. If the fulfillment of abolition lies in ensuring basic needs are met, it prompts further inquiry into the disproportionate emphasis on mutual aid over mutual comradeship and organizational discipline. Moreover, when viewing the state as a collective entity perpetuating mass incarceration through wielded power, the absence of emphasis on class struggle becomes conspicuous. This leads to a broader reflection on the intricate intersections between abolition, socialism, and the dynamics of power within a society.

Within the rhetoric of abolitionist discourse, often characterized by the envisioning of new societal paradigms (new worlds), there is a notable omission of emphasis on the practical process of ‘building towards,’ overshadowed by a prevailing idealism. This shift is not occurring in isolation; rather, it unfolds within the broader context of a mounting anti-communist sentiment that impedes a comprehensive linkage between the end goal of abolition and the final stage of communism.

Consequently, there is a noticeable absence of concerted efforts directed at organizing around workers’ struggles, encompassing issues such as employment, housing, and education, to establish a foundation for an eventual vanguard capable of securing liberated zones and community control. The current landscape is characterized by localized organizing that responds to immediate concerns rather than strategically preparing for systemic change. This is particularly evident in the negligence of recognizing domestic and global imperialism as interconnected challenges, exemplified by the expanding department of defense budget, which includes federal policing, with minimal organized resistance on a mass scale.

Internationally, the constraints of universal (read: U.S.- centric) abolition frameworks have tangible implications for the progression toward a multipolar world and, crucially, for the self-determination of the masses in those nations. I have discussed these specific contradictions and limitations in previous writing. This framework has inadvertently served the interests of the US, which uses “human rights” hypocrisy to encourage its citizens to take positions on nations it is attempting to destabilize to advance its hegemony. Whether it be the constant coverage of protests against policing or finding members of the diaspora to speak out against the “police state”, abolition, as a non- concrete framework, has been a useful tool for the U.S.’ foreign policy. Here we can see the alignment between anti-state and anti- communist rhetoric becoming synonymous with “abolition”.

The widespread adoption of the “All Cops Are Bad” (ACAB) mantra has, to some extent, oversimplified the nuanced considerations surrounding the roles of individuals within the state, blurring distinctions between those contributing to state-building for socialism and those defending the socialist project. The flippant application of “ACAB” poses a risk by oversimplifying the class character of policing, portraying it universally and equating all states, despite their diverse histories, as one and the same. This portrayal, which deems the mere existence of cops as inherently negative, discourages an exploration of the nuanced aspects of this concept.This contradiction is intensifying over time. Simultaneously, the reconsideration of a universal (read: U.S.-centric) abolition framework is ironically labeled as “counter-revolutionary.”

While I don’t inherently reject the idea of abolition, similar to my stance on decolonization, the evident issue lies in frameworks lacking clear ideologies—they tend to deviate and morph into placeholders, susceptible to individual interpretation. The problem arises when these frameworks become substitutes for personalized meanings, leading to a fragmentation of the concept. This absence of a solid ideological foundation is precisely why there is a lack of a cohesive abolition “movement” and instead an abundance of self-proclaimed abolitionists, each defining and pursuing the concept in their own way.

Where do we go from here?

Erica Caines is a poet, writer and organizer in Baltimore and the DMV. She is an organizing committee member of the anti war coalition, the Black Alliance For Peace as well as an outreach member of the Black centered Ujima People’s Progress Party. Caines founded Liberation Through Reading in 2017 as a way to provide Black children with books that represent them and created the extension, a book club entitled Liberation Through Reading BC, to strengthen political education online and in our communities.