The Wall Street Journal reported on January 4 that talks were under way as the Biden administration was seeking to establish drone bases at airfields in Ghana, Ivory Coast and Benin following a coup in Niger over the summer that jeopardized the U.S. military position there.

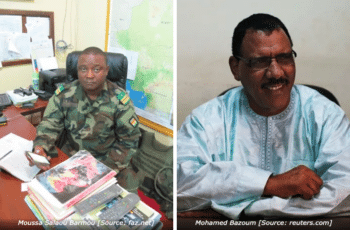

Stars and Stripes magazine reported in December that the U.S. cut the number of military personnel deployed to Niger by more than 40% in the wake of the coup, which, ironically, was led by a Special Forces officer, Moussa Salaou Barmou, trained at Fort Benning, Georgia, and the National Defense University in Washington.1

Moussa Salaou Barmou / Mohamed Bazoum

The coup plotters characterized Niger’s deposed President Mohamed Bazoum as a “corrupt pawn of France,” repudiating his support for a $110 million U.S. drone base in the desert city of Agadez, which has functioned as a hub for U.S. drone operations in West Africa.2

In a December 7 letter to Congress, the Biden administration said there are now 648 American military personnel in Niger, down from the roughly 1,100 who were there before the coup. The U.S. had been forced to end its collaboration with Niger on counterterrorism efforts in accordance with American rules that prohibit partnerships with military juntas.3

To make up for the potential “loss of Niger” (as a Western outpost that is), the Biden administration has proposed basing drones at Ghana’s Tamale Air Force Base within easy reach of the Burkina Faso border, in Parakou, Benin, a town also close to Burkina Faso, and at three potential locations in the Ivory Coast.

Agadez Air Base. [Source: lignesdefense.blogs.ouest-france.fr]

For nine months—from September 2022 to May 2023—Burkina Faso was ruled by Captain Ibrahim Traoré, who invoked the legacy of Thomas Sankara, Burkina Faso’s socialist/anti-imperialist president from 1983 to 1987, and appointed a Marxist, Pan-African ally of Sankara, Apollinaire Joachim Kyélem de Tambèla, as his prime minister.4

Considered “Africa’s Che Guevara,” Sankara was assassinated by his military commander, Blaise Compaoré, with the assistance of the U.S. and French intelligence services, which remain intent on preventing the empowerment of any political figure like him.

The Wall Street Journal made it seem like the U.S. was seeking to establish new drone bases outside of Niger because of an altruistic commitment to combating Islamic terrorism.

Captain Ibrahim Traoré and Thomas Sankara [Source: idifo.com]

Phillips wrote that,

for years, American commandos and drones backstopped French and local efforts to secure the Sahelian countries that are now at the center of the world’s most active Islamist insurgency. Since 2017, about 41,000 people have been killed in jihadist violence in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger. The disorder has created an opening for Russia to deepen ties in the region.

These latter comments parrot the view of Biden administration officials in their goal to use the threat of Russian intervention to justify their own imperialism in Africa—just like their predecessors did in the original Cold War.

Michael M. Phillips / Nick Turse

Phillips subscribes to several neo-colonial assumptions, particularly in his expressed belief that only outside powers like the U.S. and France could protect Sahelian security when historically they have fueled violence and instability while attempting to control the region’s natural resources.

Journalist Nick Turse has shown that terrorist attacks have spiked exponentially as a result of the growing U.S. military presence in the Sahelian region.

Turse points out that, in 2002 and 2003, before the creation of the U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM, which was established in 2007), the State Department counted nine terrorist attacks in all of Africa compared with 2,737 in 2022 in Burkina Faso, Mali and western Niger, and a total of 6,756 on the African continent, a 75,000% increase.

Tuareg fighters in northern Mali where they fled after the U.S.-NATO destabilized Libya under Operation Odyssey Dawn. [Source: therenegadeconflictjournal.com

The violence in Mali specifically was triggered by the 2011 U.S.-NATO invasion of Libya, which resulted in Tuareg fighters loyal to Muammar Qaddafi returning to Mali to take over the northern part of the country.

Following a coup d’état, Islamists began circumventing the Tuaregs’ attempts to forge their own independent state by attempting to impose Islamic taxes on villagers coercively and helped foment regional conflict.

In 2020, and again in 2021, Colonel Assimi Goïta, who worked with U.S. Special Operations forces and attended the Joint Special Operations University in Florida, overthrew Mali’s civilian government. He continues to receive U.S. “security” assistance that has done little to improve Malians’ security.6

Demonstrators hold signs reading “Beheaded for saying no to unconstitutional third term” and “Killed for the republic” during a march to denounce the deaths of protesters killed by Ouattara’s security forces. [Source: cnn.com]

The new drone bases, when completed, will only accelerate this latter phenomenon as the U.S. is sure to be offering the host government yet more military and security assistance in exchange for the use of real estate for the bases.

Headed by a cotton tycoon, Patrice Talon, Benin’s government has been criticized by Amnesty International for using Benin’s security forces to carry out unlawful killings during rigged 2021 elections.

The Ivory Coast has been headed since 2010 by a former International Monetary Fund employee, Alassane Ouattara, who brutally suppressed demonstrations over rigged 2020 elections and has sustained his power further by inciting ethnic violence.7

Ghana meanwhile is headed by the son of a national traitor who collaborated with the CIA in the 1966 overthrow of Kwame Nkrumah, the country’s first post-independence leader, who envisioned an independent and unified African continent that could resist Western neocolonialism through development of an All-African army and security force.8

Nkrumah would today be horrified that a leader of Ghana would allow the U.S. to establish a drone base on Ghanaian soil.

Nkrumah would today be horrified that a leader of Ghana would allow the U.S. to establish a drone base on Ghanaian soil.

He would also recognize that the official security pretexts mask the underlying aim of keeping Africa weak, divided and impoverished so the U.S. could gain an edge over geopolitical rivals like China and better exploit Africa economically.

Notes:

- ↩ At least five members of the junta in Niger were trained by the United States, according to a U.S. government official with knowledge of efforts to ascertain their American ties. According to Nick Turse, at least 15 U.S.-supported officers have been involved in 12 coups in West Africa and the greater Sahel in recent years. The list includes officers who conducted coups in Burkina Faso (2014, 2015, and twice in 2022); Gambia (2014); Guinea (2021); Mali (2012, 2020, 2021); Mauritania (2008); and Niger (2023). Chad’s Mahamat Idriss Déby—who was installed by the army in a dynastic coup after the death of his father in 2021–also benefited from U.S. assistance in 2013. See Nick Turse, “Niger Junta Appoints U.S. Trained Military Officers to Key Jobs,” The Intercept, August 16, 2023.

- ↩ The Pentagon considered the Agadez base, known as Nigerien Air Base 201, as the largest “Airman-built project” in Air Force history. It features a 6,200-foot runway for MQ-9 Reaper drones. Since 2012, the U.S. has provided at least $500 million in military aid to Niger.

- ↩ See Elian Peltier and Eric Schmitt, “After Niger Coup, U.S. Scrambles to Keep a Vital Air Base,” The New York Times, January 6, 2024.

- ↩ See Malick Doucouré, “The Military Junta in Burkina Faso,” CounterPunch, August 14, 2023, www.counterpunch.org. Doucouré wrote that “the Sankarist line…boldly taken by Captain Traoré, at least on paper, mark[ed] a radical turn from the neocolonial path, economic instability, and lack of development that…characterised his predecessor regimes. In the anti-imperialist spirit of Sankara, Western military aid [was] refused as Traoré set[] a course away from France, the EU and the U.S. French-owned foreign media channels [were] prohibited, French troops [were ordered to leave the country and military accords [were] terminated.”

- ↩ Saville quoted in Nick Turse, “Niger Coup Leader Joins Long Line of U.S. Trained Mutineers,” The Intercept, July 27, 2023.

- ↩ Assimi at one point authorized deployment of Russian Wagner mercenary forces. Military forces under his command have been linked to systemic human rights violations, including forcible disappearances, torture, and the murder of civilians.

- ↩ See Jeremy Kuzmarov, Obama’s Unending Wars: Fronting the Foreign Policy of the Permanent Warfare State (Atlanta: Clarity Press, 2019), 106.

- ↩ See Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (New York: International Publishers, 1965).