Deterrence in defense is a military strategy where one power uses the threat of reprisal to preclude attack from an adversary, while maintaining at the same time the freedom of action and flexibility to respond to the full spectrum of challenges. In this realm, the Lebanese resistance, Hezbollah, is an outstanding example.

Hezbollah’s clarity of purpose in establishing and strictly maintaining ground rules that deter Israeli military aggression has set a high regional bar. Today, its West Asian allies have adopted similar strategies, which have multiplied in the context of the war in Gaza.

America, surrounded

While the Yemeni resistance movement Ansarallah is comparable to Hezbollah in certain respects, it is the audacious brand of defensive deterrence practiced by the Islamic Resistance of Iraq that is going to be highly consequential in the near term.

Last week, citing sources in the State Department and Pentagon, Foreign Policy magazine wrote that the White House is no longer interested in continuing the U.S. military mission in Syria. The White House later denied this information, but the report is gaining ground.

The Turkish daily Hurriyet wrote on Friday that while Ankara is taking a cautious approach to media reports, it does see “a general striving” by Washington to exit not only Syria but the entire region of West Asia, as it senses that it has been dragged into a quagmire by Israel and Iran from the Red Sea to Pakistan.

Russia’s special presidential representative for the Syrian settlement, Alexander Lavrentiev, also told Tass on Friday that much depends on any “threat of physical impact” on American forces present in Syria. The swift U.S. military exit from Afghanistan took place with virtually no advance notice, in coordination with the Taliban. “In all likelihood, the same may happen in Iraq and Syria,” Lavrentiev said.

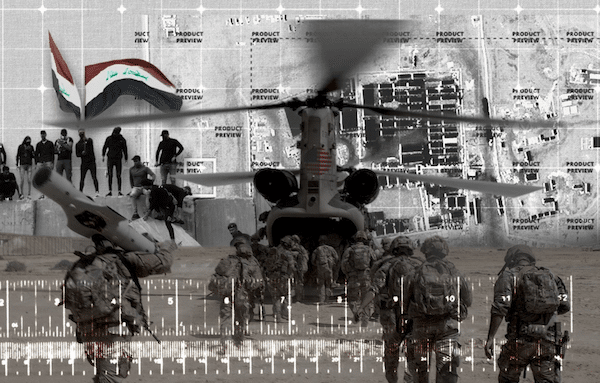

Indeed, the Islamic Resistance of Iraq has stepped up its attacks on U.S. military bases and targets. In a ballistic missile attack on Ain al-Asad airbase in western Iraq a week ago, an unknown number of American troops sustained injuries, and the White House announced its first troop deaths on Sunday when three U.S. servicemen were killed on the Syrian-Jordanian border in strikes earlier that day.

Calling Beijing for help

This situation is untenable for President Joe Biden politically–in his re-election bid next November–which explains the urgency of the National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan’s meeting with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on Friday and Saturday in Thailand to discuss the Ansarallah attacks in the Red Sea.

U.S. National Security Council spokesman John Kirby explained Washington’s rush for Chinese mediation thus:

China has influence over Tehran; they have influence in Iran. And they have the ability to have conversations with Iranian leaders that–that we can’t. What we’ve said repeatedly is: We would welcome a constructive role by China, using the influence and the access that we know they have…

This is a dramatic turn of events. While the U.S. has long been concerned about China’s growingsway in West Asia, it also needs that influence now as Washington’s efforts to reduce violence are getting nowhere. The U.S. narrative on this will be that the “strategic, thoughtful conversation” between Sullivan and Wang will not only be “an important way to manage competition and tensions [between the U.S. and China] responsibly” but also “set the direction of the relationship” on the whole.

Meanwhile, there has been hectic diplomatic traffic between Tehran, Ankara, and Moscow, as Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi traveled to Turkiye, and the moribund Astana format on Syria last week got kickstarted. Succinctly put, the three countries anticipate a “post-American” situation arising soon in Syria.

A U.S. exit from Syria and Iraq?

Of course, the security dimensions are always tricky. On Friday, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad chaired a meeting in Damascus for commanders of the security apparatus in the army to formulate a plan for what lies ahead. A statement said the meeting drew up a comprehensive security roadmap that “aligns with strategic visions” to address international, regional, and domestic challenges and risks.

Certainly, what gives impetus to all this is the announcement in Washington and Baghdad on Thursday that the U.S. and Iraq have agreed to start talks on the future of American military presence in Iraq with the aim of setting a timetable for a phased withdrawal of troops.

The Iraqi announcement said Baghdad aims to “formulate a specific and clear timetable that specifies the duration of the presence of international coalition advisors in Iraq” and to “initiate the gradual and deliberate reduction of its advisors on Iraqi soil,” eventually leading to the end of the coalition mission. Iraq is committed to ensuring the “safety of the international coalition’s advisors during the negotiation period in all parts of the country” and to “maintaining stability and preventing escalation.”

On the U.S. side, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin said in a statement that the discussions will take place within the ambit of a higher military commission established in August 2023 to negotiate the “transition to an enduring bilateral security partnership between Iraq and the United States.”

Pentagon commanders would be pinning hopes on protracted negotiations. The U.S. is in a position to blackmail Iraq, which is obliged, per the one-sided agreement dictated by Washington during the occupation in 2003, to keep in the U.S. banks all of Iraq’s oil export earnings.

But in the final analysis, President Biden’s political considerations in the election year will be the clincher. And that will depend on the calibration by West Asia’s resistance groups, and their ability to ‘swarm’ the U.S. on multiple fronts until it caves. It is this ‘known unknown’ factor that explains the Astana format meeting of Russia, Iran, and Turkiye on January 24-25 in Kazakhstan. The three countries are preparing for the endgame in Syria. Not coincidentally, in a phone call last Friday, Biden once again told Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu “to scale down the Israeli military operation in Gaza, stressing he is not in it for a year of war,” Axios‘ Barak Ravid reported in a ‘scoop’.

Their joint statement after the Astana format meeting in Kazakhstan is a remarkable document predicated almost entirely on an end to the U.S. occupation of Syria. It indirectly urges Washington to give up its support of terrorist groups and their affiliates “operating under different names in various parts of Syria” as part of attempts to create new realities on the ground, including illegitimate self-rule initiatives under the pretext of ‘combating terrorism.’ It demands an end to the US’ illegal seizure and transfer of oil resources “that should belong to Syria,” the unilateral U.S. sanctions, and so on.

Simultaneously, at a meeting in Moscow on Wednesday between the Russian Security Council Secretary Nikolay Patrushev and Ali-Akbar Ahmadian, secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, the latter reportedly stressed that Iran-Russia cooperation in the fight against terrorism “must continue, particularly in Syria.” Russian President Vladimir Putin is expected to host a trilateral summit with his Turkish and Iranian counterparts to firm up a coordinated approach.

The Axis of Resistance: deterrence means stability

Iran’s patience has run out over the U.S. military presence in Syria and Iraq following the revival of ISIS with American support. Interestingly, Israel no longer abides by its “de-confliction” mechanism with Russia in Syria. Clearly, there is close U.S.-Israeli cooperation in Syria and Iraq at the intelligence and operational level, which goes against Russian and Iranian interests. Needless to say, the backdrop of the imminent upgrade of the Russia-Iran strategic partnership also needs to be factored in here.

These developments are a vintage illustration of defensive deterrence. The Axis of Resistance turns out to be the principal instrument of peace for the issues of security that entangle the U.S. and Iran. Clearly, there isn’t any method or any reasonable hope of convergence to this process, but, fortunately, the appearance of chaos in West Asia is deceiving.

Beyond the distractions of partisan argument and diplomatic ritual, one can detect the outlines of a practical solution to the Syrian stalemate that addresses the inherent security interests of the U.S. and Iran that are embedded within an outer ring of U.S.-China concord over the situation in West Asia.

Russia may seem an outlier for the present, but there is something in it for everyone, as the pullout of U.S. troops opens the pathway to a Syrian settlement, which remains a top priority for Moscow and for Putin personally.