Dear friends,

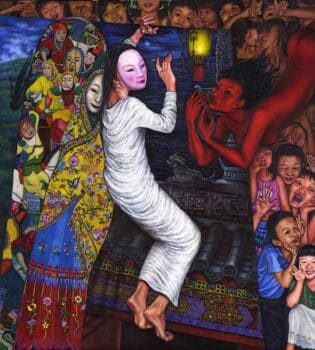

Eng Hwee Chu (Malaysia), Lost in Mind, 2008.

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

It was inevitable that the Global North governments’ full-throated support for Israel’s genocide against Palestinians would result in furious retribution from their citizenry. That this retribution began in the United States is also not a surprise, given the ongoing cycle of protests that, since October 2023, have contested the U.S. government’s blank cheque to the Israeli government. The U.S. bankrolling of Israel’s extermination campaign against Palestinians includes over one hundred weapons shipments to Israel since 7 October and billions of dollars of aid.

For a long time now, young people in the United States—as in other countries of the Global North—have felt the demise of promise from their society. Permanent precarious work awaits them, even those with higher degrees, and a more precious hold on morality has developed within them due to their own experiments to become better humans in the world. Cruelties of austerity and of patriarchal norms have forced them to turn against their ruling classes. They want something better. The assault against Palestinians has spurred a rupture. How much further these young people will go is yet to be seen.

Across the United States, students have built encampments on over a hundred of university campuses, including the country’s most prestigious institutions such as Columbia, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Stanford, Emory, Washington University in St. Louis, Vanderbilt, and Yale. The students are part of a range of local campus groups as well as national organisations, among them Students for Justice in Palestine, the Palestinian Youth Movement, Jewish Voice for Peace, CodePink, the Democratic Socialists of America, and the Party for Socialism and Liberation. At these encampments, students sing and study, pray and discuss. These universities have invested their vast endowments in funds that are entangled with the weapons industry and Israeli companies, with the total endowments at U.S. institutions of higher education reaching roughly $840 billion. Seeing their ever-expanding tuition payments go towards institutions that are complicit in and profiting from this genocide is far too much for these students. Hence their determination to resist with their bodies.

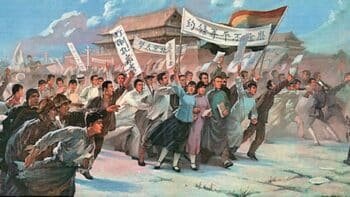

Liang Yulong (China), May Fourth Movement, 1976.

Democracy is corroded when basic civil actions such as this are met with the full force of the state’s repressive apparatus. College administrators and local urban authorities have sent in heavily armed police forces to use any means necessary to remove the encampments, further reinforced by placing snipers on campus rooftops at multiple universities. Scenes of sensitive students and faculty members being ripped away from their campuses, tased, brutalised, and arrested by police in riot gear are scattered across social media. But rather than demoralise the youth, these violent measures have simply sparked the creation of new encampments at colleges not only in the United States, but in countries as far afield as Australia, Canada, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Excuses such as the tents being a fire hazard might stiffen the resolve of the administrators, but they make no sense to the students, the faculty members who came out to defend them, or concerned people around the world. The images of this violence are reminiscent of the photographs of the massacres against U.S. students protesting the Vietnam War and of police dogs being unleashed on young Black children during the U.S. civil rights movement.

This is not the first time that young people, particularly college students, have tried to impose clarity upon a world encrusted by compromises. In the United States, earlier generations fought to get their colleges to divest from apartheid South Africa and from the ugly U.S.-driven wars in Southeast Asia and Central America. In 1968, young people from France to India, from the United States to Japan, erupted in anger at the imperialist wars in Algeria, Palestine, and Vietnam, their eyes firmly set on Paris, Tel Aviv, and Washington for their murderous culture. Their attitude was captured by the Pakistani poet Habib Jalib, who sang at Lahore’s Mochi Gate kyun darate ho zindan ki divar se (why do you scare me with the prison’s gate?), and then zulm ki baat ko jahl ki raat ko, main nahin manta main nahin jaanta (oppression’s words, ignorance’s night, I refuse to acknowledge, I refuse to accept).

Nidhal Chamekh (Tunisia), Dessin 8, 2012.

Since we are at the start of May, it might be valuable to recall the brave young people of China who took to the streets on 4 May 1919 to condemn the humiliations forced upon the Chinese people during the Paris Peace Conference (which resulted in the Treaty of Versailles). During the conference, the imperialist powers decided to give Japan a large part of the Shandong Province, which Germany had seized from China in 1898. In this transfer of power, Chinese youth saw the weakness of China’s republic, which had been set up in 1911. Over four thousand students from thirteen universities in Beijing took to the streets under a banner that read ‘Strive for sovereignty externally, eliminate national traitors internally’. They were angry both at the imperialist powers and their own sixty-member delegation to the Paris conference, led by Minister of Foreign Affairs Lu Zhengxiang. Liang Qichao, a member of the delegation, was so frustrated with the treaty that he sent a bulletin back to China on 2 May, which was published and spurred on the Chinese students. The student protests pressured the Chinese government to dismiss pro-Japanese officials such as Cao Rulin, Zhang Zongxiang, and Lu Zongyu. On 28 June, the Chinese delegation in Paris refused to sign the treaty.

The actions of the Chinese students were powerful and far-reaching, with their May Fourth Movement not only protesting the Treaty of Versailles but unfolding a broader critique of the rot in China’s elite republican culture. The students wanted more, their patriotism finding shelter in currents of left-wing thought such as anarchism but more profoundly in Marxism. Just two years later, several of the important young male intellectuals that were shaped by this uprising, such as Li Dazhao, Chen Duxiu, and Mao Zedong, founded the Communist Party of China in 1921. Women leaders founded organisations that brought millions of women into political and intellectual life, later becoming core elements of the Communist Party. For instance, Cheng Junying founded the Beijing Women’s Academic Federation; Xu Zonghan established the Shanghai Women’s Federation; Guo Longzhen, Liu Qingyang, Deng Yingchao, and Zhang Ruoming created the Tianjin Women’s Patriotic Comrades Association; and Ding Ling became one of the leading storytellers of China’s countryside. Thirty years after the May Fourth Movement, many of these men and women displaced their rotten political system and established the People’s Republic of China.

Who knows where the refusals of students in the Global North today will go. The students’ refusal to acknowledge the excuses of their ruling class and accept its policies are dug deeper into their soil than their tents. The police can arrest them, brutalize them, and displace their encampments, but this will only make radicalization harder to disrupt.

Who knows where the refusals of students in the Global North today will go. The students’ refusal to acknowledge the excuses of their ruling class and accept its policies are dug deeper into their soil than their tents. The police can arrest them, brutalize them, and displace their encampments, but this will only make radicalization harder to disrupt.

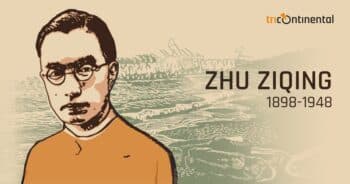

In the midst of the white heat of the May Fourth Movement, the poet Zhu Ziqing (1898—1948) wrote ‘Brightness’. His words rush from 1919 to our own time, from one generation of students to another:

In the deep and stormy night,

Ahead lies a barren wilderness.

Once past the barren wilderness,

There lies the path of the people.

Ah! In the darkness, countless paths,

How should I tread correctly?

God! Quickly give me some light,

Let me run forward!

God quickly replies, Light?

I have none to find for you.

You want light?

You must create it yourself!

That is what young people are doing: they are creating this light, and, even as many of their elders try to dim it, the brightness of their souls continues to illuminate the wretchedness of our system—at its heart the ugliness of Israel’s war—and the promise of humanity.

Warmly,

Vijay