How can we trace the wounds of colonialism in the art historical record? What forms do they take and how can we recognize them? In the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, the historical record holds many stories about the vibrancy of material and visual culture in forging an anticolonial consciousness. Black, Indigenous, and mixed-race artists created and circulated portraits, medallions, banners, prints, and talismans to galvanize support for coordinated uprisings that sought to dismantle the co-constitutive institutions of slavery and colonial rule. The Tupac Amaru Rebellion (1780-1783) of the southern Andes, the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804), and the Aponte Rebellion (1812) of Cuba, among countless other uprisings, are rife with accounts of artworks as critical intercessors in the creation of an anticolonial and radical abolitionist imaginary. Yet these stories arrive to us in battered, fragmented form, whether as ekphrastic descriptions in the scrawl of a notary furiously transcribing the courtroom confessions of the artist, or bare threads of a canvas whose pigments had been scraped away to excise the visage of a former rebel. The art histories of Black and Indigenous struggles for liberation are marked by profound and violent erasure; acts of imperial iconoclasm overseen by colonial officials functioned not only to silence insurgent counter-visualities but also to supplant them with absolutist imagery to reassert colonial control.

Given the precarious post-rebellion landscape, colonial officials prioritized the erasure of memory—borrar la memoria was a widespread trope in the archival and published documents surrounding anticolonial uprisings and slave rebellions in the Spanish Americas—which they attempted most notably through iconoclastic campaigns to destroy or efface offending images. State-sanctioned erasures, however, also produced their own material and performative excesses; the destruction of memory necessitated the widespread proliferation of cultures of surveillance in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world, a proliferation reflected in cartographic illustrations, portraits of the viceroy, and royal medals. I include these forms of visual culture within the rubric of what Nicholas Mirzoeff terms “surrogates of the sovereign,” which sought to maximize the gaze of the absent monarch through both the reproduction of his visage and the aesthetic performance of mastery over Andean landscapes that had otherwise been used to the tactical advantage of rebel forces deeply familiar with their contours. The Spanish king’s absence from American soil required a robust apparatus of material surrogates that amplified his omnipresence, particularly in the aftermath of uprisings that threatened the future of colonial rule. Surrogation was also a defining feature of the evangelizing imperative in early colonial Latin America; as Diana Taylor argues, the spread of localized Virgins within Mesoamerica produced deep anxieties on the part of friars whose writings centered on a recurring trope of whether Nahua deities had been effectively replaced or if they simply lived on in surrogate form.

Yet surrogation, as Joseph Roach has amply demonstrated, can also serve as a strategy of cultural resiliency for recovering the voids and silences produced by colonization. His theorization of surrogacy offers a critical framework for interpreting performance and expressive culture in the circum-Atlantic world. He posits that surrogation serves as an engine of social memory that fills “the cavities created by loss through death or other forms of departure.” Other scholars such as David Lambert have extended Roach’s concept of surrogation to interpret commemorative statues in postcolonial Barbados Building on these formulations, I employ surrogacy as a strategy for cohering fractured object histories to magnify their historical presence in the eighteenth-century Atlantic world.

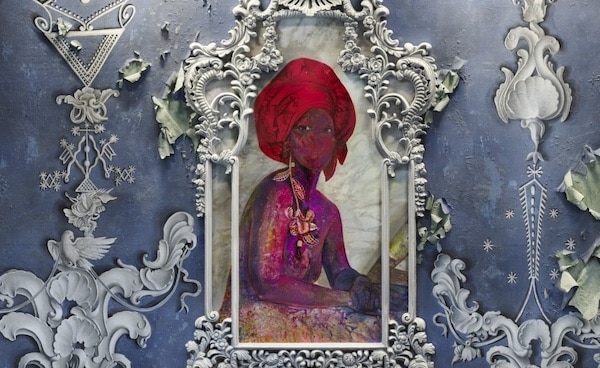

Can we thus use surrogacy to reimagine the transmission of liberatory aesthetics in the absence of an enduring corpus of surviving artworks? In advancing a decolonial approach to the deliberate fragmentation of the visual record of anticolonial and antislavery uprisings, an exploration of surrogate images can open up possibilities for reconstituting discontinuous temporal and geographical contexts of liberation movements across the Americas. From identifying contemporaneous approximations of now-lost early modern objects to considering contemporary reimaginings of historical figures who no longer survive in the artistic record, visual surrogates can help us write histories of art in contexts where the possibility of an intact material afterlife was foreclosed by colonial suppression. Assembling constellations of artists, artworks, and visual surrogates across multiple geographic and temporal contexts can make possible an otherwise inaccessible art historical narrative. This art history participates in a recuperative vision of the aesthetics of uprisings across the hemisphere, a vision that connects past and present in imagining alternative futures.