Part 7 of my article on the causes and implications of global capitalism’s descent into an era when infectious diseases are ever more common. My views are subject to continuing debate and testing in practice. I look forward to your comments, criticisms, and corrections.

- Part 1: An Existential Threat

- Part 2: Relentless Viral Evolution

- Part 3: Systematically Unprepared

- Part 4: Deforestation and Spillover

- Part 5: The Pandemic Machines

- Part 6: China’s Livestock Revolution

- Part 7: Wildlife Farms and Wet Markets

In the late 1980s, China’s government began encouraging farmers who had been squeezed out of swine and poultry markets to switch to non-traditional livestock. The 1988 National Peoples Congress declared that wildlife was a resource to be used for economic development, and in 2004 the commercial breeding of 54 wild species was officially approved. National and state agencies were instructed to “to actively promote the breeding and market supply of terrestrial wild animals for which mature breeding technology had been developed.”1

These figures do not include the illegal wildlife trade, which is extensive.

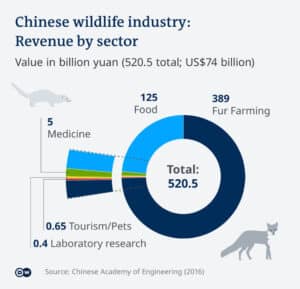

That opening attracted private investment and rapid growth: in 2016 the Chinese Academy of Engineering estimated that the legal wildlife industry employed over 14 million people and sales totaled close to US$74 billion a year. Detailed statistics are not available, but in 2020 it was reported that nearly 20,000 farms were raising wild animals for sale as food.2 Species involved included bamboo rats, pangolins, peacocks, palm civets, raccoon dogs, porcupines, boars, and many others.

The traditional food myth

Articles on the wild animal trade in China frequently describe eating exotic animals as an ancient feature of Chinese culture, perpetuated by ignorant peasants who have migrated to the cities. Often this is offered as a racist caricature, proof that Chinese eating practices are unclean, cruel and barbaric.

In fact, as Dr. Peter J. Li, a leading authority on animal welfare in China, says,

the majority of the people in China do not eat wildlife animals.3

“The claim that such wildlife consumption is traditional, that it can be traced back to ancient China, and that there is a demand for wild animal meats is misinformation spread and perpetuated by the country’s wildlife breeders and owners of exotic food restaurants. I have studied China’s wildlife farming and restaurant industry for the last two decades. Never have I found evidence to support the claim that China had a tradition of widespread wildlife consumption…

China’s massive wildlife farming operations and related businesses such as the production of wildlife feed, trans-provincial transport of live captive-bred and hunted animals, production of veterinary drugs, and the hundreds of thousands of exotic food restaurants are part of a business empire that has arisen in the last 40 years. Attributing this wildlife-exploiting empire to traditional Chinese culture, and thereby suggesting that it is something to be proud of, is a tactic designed by businesses to shut up the critics.4

In a 2020 survey, 97% of Chinese citizens opposed eating wild animals, and 79% opposed the use of fur and other wildlife products.5 A 2014 study found that eating wildlife was part of “a fashionable lifestyle and symbol of elite status,” and that “consumers with higher income and higher educational background had higher wildlife consumption rates, and formed the main consumer group of wild animals.”6

Most wild animals bred for food are sold to restaurants that cater to the urban elite–managers and officials who can afford expensive meals and for whom eating and serving exotic animals is a respected form of conspicuous consumption.

(It should be noted that conspicuous consumption of wildlife by the rich isn’t unique to China.

American trophy hunters pay big money to kill animals overseas and import over 126,000 wildlife trophies per year… just for bragging rights.7

Wild animal farming, then, is not a continuation of traditional practices, but an extension of the industrialization and commodification of all livestock–in this case, the industrialization and commodification of luxury foods for the wealthy. This is not tradition–it is modern capitalism in action.

Wet markets

Wet markets are retail centers for the sale of perishable foods–they are wet because water and ice keep the produce fresh and clean. Most sell only butchered meat, seafood, vegetables and fruit. For hundreds of millions of people around the world, particularly in east and southeast Asia, they are essential sources of food and nutrition. Despite common western misconceptions, live animals are not sold and slaughtered in all wet markets, and only a minority of live animal vendors–primarily wholesalers who sell to restaurants and caterers–deal in farmed or hunted wild animals.

Nevertheless, the wildlife trade can pose significant dangers to human health. The president of the Chinese Medical Association and head of the Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases drew this conclusion from the 2002-3 SARS epidemic,

Wildlife markets represent a dangerous source of possible new infections that could undermine the prevention of SARS… Many markets are poorly managed and insanitary, so cross infection, interspecies transmission, amplification, genetic convergence, and mixing of coronavirus may be taking place. Animal traders standing in close proximity to these infected animals may be affected, as may the food processors who slaughter infected animals in restaurant kitchens, causing SARS-CoV to spread from wildlife to humans–after which it may spread from human to human.8

More recently, a report published by the United Nations Environment Program warned that,

any significant increase in the farming of wild animals risks ‘recapitulating’ the increases in zoonoses that likely accompanied the first domestication of animals in the Neolithic era, some 12,000 years ago.9

In theory, wildlife farms could provide proper sanitary conditions that reduce the risk of disease transmission. But in reality, the risk of disease transmission with wildlife farms is significant…

A mix of animal species are traded in markets–wild, captive-bred, farmed and domesticated–in transport vehicles and in market cages…

The close contact between humans and different species of wildlife in the global wildlife trade can facilitate animal-to-human spillover of new viruses that are capable of infecting diverse host species. This can trigger emerging disease events with higher pandemic potential because these viruses are more likely to amplify via human-to- human transmission, and thus spread widely.10

Relentless evolution

Palm Civet

Viruses never stop evolving, and coronaviruses evolve particularly quickly. In the nature of things, we see only evolution’s successes, because the failures don’t survive or reproduce–so we have no way of knowing how many mutated viruses have jumped unsuccessfully from wild animals to farmed animals.

What we do know is that sometime in 2002, a previously unknown coronavirus, probably recently evolved in horseshoe bats, infected farmed palm civets in southern China. Infected civets were transported to wet markets in Guangdong province, where the virus spread to other civets, mutating further before spilling over to humans.11

The result was Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome–SARS–the first pandemic of the 21st Century. The pneumonia-like disease broke out in Guangdong in November 2002, then spread to 29 other countries, infecting about 8100 people and killing at least 774.

A strong connection between the initial outbreak and live animal markets was obvious from the beginning. “Around 40% of early patients were food handlers with probable animal contact; most of these patients lived closer to wet markets than to animal farms, suggesting that markets, not farms, were the initial source of transmission.”12 Bans on the sale of small mammals for food, combined with a mass cull of farmed civets, contributed to the rapid suppression of SARS.

Unfortunately, the bans were soon lifted, under pressure from food industry lobbyists. Over the next 15 years, industrial wildlife farming expanded alongside industrial farming of poultry and pigs, using the same production methods, the same transportation systems, and often the same markets.

Eventually–we can even say inevitably–relentless evolution produced another new coronavirus, this one less deadly but much more contagious than SARS. It initially formed in wild bats and then jumped to farmed wild animals that were taken for sale in Wuhan, China’s seventh largest city. The exact transmission path is still not known, but late in 2019 the new virus jumped to humans in the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, the largest live animal market in central China.

Speculation that the virus came from a laboratory had some credibility in the early days of the pandemic but the idea has long since been refuted. The most recent and complete summary of published research found no evidence that the virus came from a lab, and concluded that “the available data clearly point to a natural zoonotic emergence within, or closely linked to, the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan.”13

A virus on the move

In the last two weeks of 2019, 41 people in Wuhan were hospitalized with a previously unknown, pneumonia-like disease, and two-thirds of those had had direct exposure to the Huanan Market. On January 1, authorities shut down and disinfected the market, but the virus had already escaped.

Wuhan has long been an important transportation hub, but the number of high-speed trains, express highways and flights connecting it to the rest of China and the world has increased radically since 2000.

Travel times between Wuhan and Beijing or Guangzhou dropped from about twelve to four hours, and annual railway passengers increased from about 1 billion in 2000 to over 3.3 billion in 2018. … In 2000, Wuhan’s main airport served 1.7 million passengers with 34,000 domestic flights. By 2018, over 27.1 million passengers traveled through Wuhan’s airport on 203,000 flights, including sixty-three international routes.14

Those connections, direct products of China’s spectacular economic growth, transported the new virus at unprecedented speed. It was carried by people who could not have known they were infected, because SARS-CoV-2 is contagious for several days before symptoms appear. Literally millions of people left Wuhan in January, most travelling home for the annual Spring Festival, and–as always happens in epidemics–many hoping to escape the mysterious new disease.

Within weeks, the virus had reached most Chinese provinces and at least a dozen other countries in Asia, Europe and North America. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern,” the official term for a pandemic. On February 11, the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses confirmed that the new virus was genetically related to the one that caused SARS in 2002, and named it SARS-CoV-2. On the same day, the WHO named the disease COVID-19.16

The threat remains

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Chiba imposed a permanent ban on farming wildlife for food. If it is effectively enforced, that is a public health measure that other countries should emulate, but it is far from being an adequate response to the zoonotic disease threat. Two critical problems stand out.

First, the ban applies only to farms that raise wild animals for food–representing less than a quarter of wildlife industry revenues. Farms that raise wild animals for fur, traditional medicines and other purposes are exempt, even though some of those animals are known to carry coronaviruses and other potential pathogens, so many thousands of wild animal (and wild virus) breeding operations remain active. The animals may not be eaten or sold in wet markets, but since most viral diseases can be contracted by breathing or physical contact, they can infect and be spread by the people who work with them.

Second, and more important, the ban does not affect the poultry, swine, and other “domesticated” animals that are raised in facilities that are far larger and more numerous than wildlife farms. As discussed in Part 6, there is a continuing drive–strongly supported by the government’s economic development policies–to build ever larger concentrated animal feeding operations, increasing the danger of new and larger zoonotic disease outbreaks.

As Li Zhang writes, the only effective method of reversing the trend towards more zoonotic diseases would be to “dismantle those unsustainable agroindustries… and deconcentrate both animals and humans from unban metropolises.”16 If megafarms continue to grow and spread, in China, the United States and elsewhere, it is very likely that industrial livestock production will cause another global pandemic.

Footnotes:

- ↩ Amanda Whitfort, “COVID-19 and Wildlife Farming in China: Legislating to Protect Wild Animal Health and Welfare in the Wake of a Global Pandemi c,” Journal of Environmental Law 33, no. 1 (April 23, 2021): 57—84.

- ↩ Michael Standaert, “Coronavirus Closures Reveal Vast Scale of China’s Secretive Wildlife Farm Industry,” The Guardian, February 25, 2020, sec. Environment.

- ↩ Peter J. Li, Vox interview, March 6, 2020.

- ↩ Peter J. Li, Animal Welfare in China: Culture, Politics and Crisis (University of Sydney, N.S.W: Sydney University Press, 2021), 213—14.

- ↩ Anna McConkie, “Illegal Wildlife Trade in China,” Ballard Brief, Fall 2021.

- ↩ Li Zhang and Feng Yin, “Wildlife Consumption and Conservation Awareness in China: A Long Way to Go,” Biodiversity and Conservation 23, no. 9 (August 2014): 2279.

- ↩ Humane Society of the United States, “Banning Trophy Hunting,” 2024.

- ↩ Nanshan Zhong and Guangqiao Zeng, “What We Have Learnt from SARS Epidemics in China,” BMJ 333, no. 7564 (August 19, 2006): 389—91.

- ↩ Delia Grace Randolph, “Preventing the Next Pandemic: Zoonotic Diseases and How to Break the Chain of Transmission” (Nairobi: United Nations Environment Program, 2020), 16.

- ↩ Delia Grace Randolph, 33.

- ↩ Jie Cui, Fang Li, and Zheng-Li Shi, “Origin and Evolution of Pathogenic Coronaviruses,” Nature Reviews Microbiology 17, no. 3 (March 2019): 181—92.

- ↩ Bing Lin et al., “A Better Classification of Wet Markets Is Key to Safeguarding Human Health and Biodiversity,” The Lancet Planetary Health 5, no. 6 (June 2021): e386—94.

a - ↩ (Edward C. Holmes, “The Emergence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2,” Annual Review of Virology, April 17, 2024. See also Phillip Markolin’s excellent technical report, “Treacherous Ancestry: An Extraordinary Hunt for the Ghosts of SARS-CoV-2,” Protagonist Science, April 11, 2024.

- ↩ Li Zhang, The Origins of COVID-19: China and Global Capitalism (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2021), 34—35.

- ↩ Dali L. Yang, Wuhan: How the COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan, China Spiraled out of Control(New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2024), 2.

- ↩ Zhang, The Origins of COVID-19, 133.