Janine Jackson: If you use the word “democracy” unsarcastically, you likely think it has something to do with, not only every person living in a society having some say in the laws and policies that govern them, but also the idea that everyone should be able to know what’s going on, besides voting, that influences that critical decision-making.

“Dark money,” as it’s called, has become, in practical terms, business as usual, but it still represents the opposite of that transparency, that ability for even the un powerful to know what’s happening, to know what’s affecting the rules that govern our lives. A press corps concerned with defending democracy, and not merely narrating the nightmare of crisis, would be talking about that every day, in every way.

Our guest has written about the gap between what we need and what we get, in terms of media. Steve Macek is professor and chair of communication and media studies, at North Central College in Illinois, a co-coordinator of Project Censored’s campus affiliate program, and co-editor and contributor to, most recently, Censorship, Digital Media and the Global Crackdown on Freedom of Expression, out this year from Peter Lang. He joins us now by phone from Naperville, Illinois. Welcome to CounterSpin, Steve Macek.

Progressive (6/24)

Steve Macek: Thanks for having me, Janine. I’m a big fan of the show.

JJ: Well, thank you. Let’s start with some definition. Dark money doesn’t mean funding for candidates or campaigns I don’t like, or from groups I don’t like. In your June piece for the Progressive, you spell out what it is, and where it can come from, and what we can know about it. Help us, if you would, understand just the rules around dark money.

SM: Sure. So dark money, and Anna Massoglia of OpenSecrets gave me, I think, a really nice, concise definition of dark money in the interview I did with her for this article. She called it “funding from undisclosed sources that goes to influence political outcomes, such as elections.” Now, thanks to the Supreme Court case in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission in 2010, and some other cases, it is now completely legal for corporations and very wealthy individuals to spend unlimited amounts of money to influence the outcomes of elections.

Not all of that “independent expenditure” on elections is dark money. Dark money is spending that comes from organizations that do not have to disclose their donors. One sort of organization, I’m sure your listeners are really familiar with, are Super PACs, or, what they’re more technically known as, IRS Code 527 organizations. It can take unlimited contributions, and spend unlimited amounts on influencing elections, but they have to disclose the names of their donors.

There’s this other sort of organization, a 501(c)(4) nonprofit, which is sometimes known as a “social welfare nonprofit,” who can raise huge amounts of money, but they do not have to disclose the names of their donors, but they are prevented from spending the majority of their budget on political activity, which means that a lot of these 501(c)(4) organizations spend 49.999% of their budget attempting to influence the outcomes of elections, and the rest of it is spent on things like general political education, or research that might, in turn, guide the creation of political ads and so on.

Guardian (5/17/24)

JJ: When we talk about influencing the outcome of elections, it’s not that they are taking out an ad for or against a particular candidate. That doesn’t have to be involved at all.

SM: Right. So they can sometimes run issue ads. Sometimes these dark money groups, as long as they’re working within the parameters of the law, will run ads for or against a particular candidate.

But take, for example, Citizens for Sanity, the group that I talked about at the beginning of my Progressive article: This is a group that nobody knows very much about. It showed up back in 2022, and ran $40 million worth of ads in four battleground states. Many of the ads were general ads attacking the Democrats for wanting to erase the border, or over woke culture-war themes, but they’re spending $40+ million on ads, according to one estimate.

What we do know is the officials of the group are almost identical to America First Legal, which was made up by former Trump administration officials. America First Legal was founded by Stephen Miller, that xenophobic former advisor and sometimes speechwriter to Donald Trump. No one really knows exactly who is funding this organization, because it is a 501(c)(4) social welfare nonprofit, and so is not required by the IRS to disclose its donors.

It has been running this year, in Ohio and elsewhere, a whole bunch of digital ads, and putting up billboards, for example, attacking Democratic Sen. Sherrod Brown for his stance on immigration policies, basically saying he wants to protect criminal illegals, and also running these general, very snarky anti-“woke” ads saying, basically, Democrats used to care about the middle class, now they only care about race and gender and DEI.

JJ: Right. Well, I think “rich people influence policy,” it’s almost like “dog bites man” at this point, right? Yeah, it’s bad, but that’s how the system works, and I think it’s important to lift up: If it didn’t matter for donors to obscure their support for this or that, well then they wouldn’t be trying to obscure it.

And the thing you’re writing about, these are down-ballot issues, where you might believe that Citizens for Sanity, in this case, or any other organization, you might think of this as like a grassroots group that’s scrambled together some money to take out ads. And so it is meaningful to know to connect these financial dots.

SM: Absolutely. It is meaningful. And since you made reference to down-ballot races, one of the things that I think is so nefarious about dark money, and these dark money organizations, is that they are spending a lot on races for things like school boards or, as I discussed in the article, state attorney generals races.

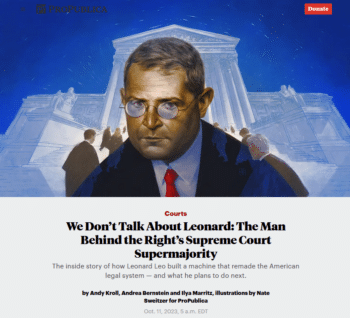

ProPublica (10/11/23)

There is this organization, it was founded in 2014, called the Republican Attorneys General Association, or RAGA, which is a beautiful acronym, and they have been trying to elect extremely reactionary Republicans to the top law enforcement position in state after state. And in 2022, they spent something like $8.9 million trying to defeat Democratic state attorney generals candidates in the 2022 elections.

Now, they are a PAC of a kind, they’re a 527, so they have the same legal status as a Super PAC, so they have to disclose their donors. But the fact is, one of the major donors is a group called the Concord Fund, which has given them $17 million.

Concord Fund is a 501(c)(4) that was founded by Leonard Leo, the judicial activist affiliated with the Federalist Society, who is basically Donald Trump’s Supreme Court whisperer, who is largely responsible for the conservative takeover of the federal courts. His organization, this fund that he controls, gave $17 million to RAGA.

And we have no idea who contributed that money to the fund. We can make some educated guesses, but nobody really knows who’s funneling that money into trying to influence the election of the top law enforcement official in state after state around this country.

That’s alarming because, of course, some of these right-wing billionaires and corporations have a vested interest in who is sitting in that position. Because if it comes to enforcement of antitrust laws, or corruption laws, if they have a more friendly state attorney general in that position, it could mean millions of dollars for their bottom line.

JJ: And I think, from the point of view of the public, filtered through the point of view of the press, if you heard there’s this one macher, or this one rich person, and they’re pulling the strings and they’ve bought this judge, and they’ve paid for this policy and these ads, that would be one thing. But to have it filtered through a number of groups that are kind of opaque and you don’t really know, a minority point of view can be presented as a sort of groundswell of grassroots support.

Colorado Newsline (10/21/23)

SM: Exactly. It can create this sort of astroturfing effect where, “Oh, there are all these ads being run. It must be that there are lots of people who are really concerned or really opposed to this particular candidate,” when, in fact, it could be a single billionaire who is routing money for a number of different shells and front groups in an effort to influence the outcome of an election.

So I think attorney generals races are one kind of down-ballot race where we’ve seen a lot of dark money spent. School board elections are another, and this is something that has been really evident in the past couple of years, where various different Super PACs and other dark money groups have spent millions of dollars, that are affiliated with advocates for charter schools, and advocates for school vouchers have been spending money trying to elect school board members that are pro-voucher and pro—charter school.

In 2023, City Fund, which is a national pro—charter school group, bankrolled in part by billionaire Reed Hastings, donated $1.75 million from its affiliated PAC to a 501(c)(4), Denver Families for Public Schools, to try to elect three “friendly” pro—charter school candidates for the city school board, and all three of the candidates won.

And I don’t know about you, but I don’t have children who went through the public system here in Naperville, I didn’t pay very close attention to who was running in those races, or who was backing those people. I just would read about it a couple days before the election. Most people don’t pay very close attention, unless they’re employees of the school district, or have children currently in school. They’re not paying that close attention to the school board elections. And so this influx of dark money could very well have tipped those races in the favor of the pro—charter school.

JJ: And name that group again, because it didn’t say “charter schools.”

SM: So the charter school group was City Fund, and it donated money to Denver Families for Public Schools….

JJ: : For “public schools….”

SM: Right, which is a 501(c)(4) nonprofit. Yes, and it’s got this Orwellian name, because it’s Denver Families for Public Schools. But what they wanted to do was, of course, create more charter schools.

ProPublica (12/14/22)

JJ: It’s deep, and it’s confusing because it’s designed to be confusing, and it’s opaque because, you know….

And then, OK, so here come media. And we know that lots of people, including reporters, still imagine the U.S. press corps as kind of like an old movie, with press cards in their hat band, or Woodward and Bernstein connecting dots, holding the powerful to account, and the chips are just falling where they may.

And you make the point in the Progressive piece that there have been excellent corporate news media exposés of the influence of dark money, connecting those dots. But you write that news media have “missed or minimized as many stories about dark money as they have covered.” What are you getting at there?

SM: I absolutely believe that. So it is true, as I say, that there have been some excellent reports about dark money. Here in Chicago, we had this reclusive billionaire industrialist, Barre Seide, who made what most people say is the largest political contribution in American history. He donated his company to a fund, Marble Freedom Fund, run by Leonard Leo, again, a conservative judicial activist.

The Marble Freedom Fund sold the company for $1.6 billion. It’s hard for the corporate media to ignore a political contribution of $1.6 billion. That’s a $1.6 billion trust fund that Leonard Leo, who engineered the conservative takeover of the U.S. Supreme Court, is going to be able to use—he’s a very right-wing, conservative Catholic—to put his particular ideological stamp on American elections and on American culture. And so that got reported.

And, in fact, there have been some really excellent follow-up reports by ProPublica, among others, about how various Leonard Leo—affiliated organizations have influenced judicial appointments and have influenced judicial elections. So you have to give credit where credit’s due.

But the problem is that there are so many other cases where dark money is in play. Whether or not you can say it’s determining the outcome of elections or not is another story. But where dark money is playing a role, and it is simply not being talked about.

Steve Macek: “Outside forces who, in some cases, do not have to disclose the source of their funding can spend more on a race than the candidates themselves.”

Think about the last month of this current presidential election. There hasn’t been much discussion about the influence of dark money. And yet OpenSecrets just came out with an analysis where they say that contributions from dark money groups and shell organizations are outpacing all prior elections in this year, and might surpass the $660 million in contributions from dark money sources that flooded the 2020 elections. So they’re projecting that could be as much as a billion dollars. We haven’t heard very much about this.

I don’t think necessarily dark money is going to make a huge difference one way or the other in the presidential race, but it certainly can make a difference in congressional races and attorney generals races, school board races, city council races, that’s where it can make a huge difference.

And I do know that OpenSecrets, among others, have done research, and they found that there were cases where, over a hundred different congressional races, there was more outside spending on those races than were spent by either of the candidates. Which is a scandal, that outside forces who, in some cases, do not have to disclose the source of their funding can spend more on a race than the candidates themselves.

JJ: And it’s disheartening, the idea that, while you’re swimming in it, it’s too big of an issue to even lift out.

SM: And I think that’s also part of the reason why it’s accepted, sort of like the weather. And I think that’s part of the reason why there isn’t as much reporting in the corporate media as there ought to be about legal struggles over the regulation of dark money.

JJ: That’s exactly where I was going to lead you, for a final question, just because we know that reporters will say, well, they can’t cover what isn’t happening. But it is happening, that legal and community and policy pushback on this influence is happening. And so, finally, what should we know about that?

SM: State-level Republican lawmakers, and state legislatures across the country, are pushing legislation that would prohibit state officials and agencies from collecting or disclosing information about donors to nonprofits, including donors to those 501(c)(4) social welfare organizations that I spoke about, that spend money on politics. So they’re trying to pass laws to make dark money even darker, to make this obscure money influencing our elections even harder to track. And I will say there are Republicans in Congress who have introduced federal legislation that would do the same thing.

Roll Call (5/14/24)

Now, the bills that are being pushed through state legislatures, not probably going to be a surprise to anybody who follows this, are based on a model bill that was developed by the American Legislative Exchange Council, or ALEC, which is a policy development organization that is funded by the Koch network of right-wing foundations, millionaires and billionaires. And they meet every year to develop model right-wing, libertarian legislation, that then is dutifully introduced into state legislatures around the country.

And since 2018, a number of states, including Alabama, Arizona, Iowa, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah, Virginia and West Virginia, have all adopted some version of this ALEC legislation that criminalizes disclosing donors to nonprofits that engage in political activity.

And in Arizona, where this conservative legislation was made into law, in 2022, there was a ballot referendum by the voters on the Voter’s Right to Know Act, Proposition 211, that would basically reverse the ALEC attempt to criminalize the disclosure of the names of donors. It would require PACs spending at least $50,000 on statewide campaigns to disclose all donors who have given more than $5,000—a direct reversal of the ALEC-inspired law.

Conservative dark money group spent a lot of money trying to defeat this, and yet they lost. And then they spent a lot of money challenging the new law, Proposition 211, in court. And it has gone to trial, I think, three times, and been defeated each time.

Now, the initial battle over Proposition 211 was covered to some degree in the corporate media, the New York Times, Jane Mayer at the New Yorker, who does excellent reporting on dark money issues, discussed it. But since then, we have gotten very little coverage of the court battles that continue to this day over this attempt to bring more transparency to campaign spending in the state of Arizona.

New Yorker (11/16/22)

JJ: So, not to hammer it too hard home, but there are legal efforts, policy efforts around the country, to bring more transparency, to explode this idea of dark money, to connect the dots, and more media coverage of them would actually have an amplifying effect on that very transparency.

SM: Absolutely right. You would think that media organizations, whether they’re corporate or independent media, would have a vested interest in seeing more transparency in election spending. That would benefit their own reporting, and the reporters. And yet they really haven’t done a great job of covering it.

JJ: We’ve been speaking with Steve Macek. He’s professor and chair of communication and media studies at North Central College in Illinois, and a co-coordinator of Project Censored’s campus affiliate program. The piece we’re talking about, “Dark Money Uncovered,” can be found at TheProgressive.org. Steve Macek, thank you so much for joining us this week on CounterSpin.

SM: Oh, it was great. Thank you for having me.