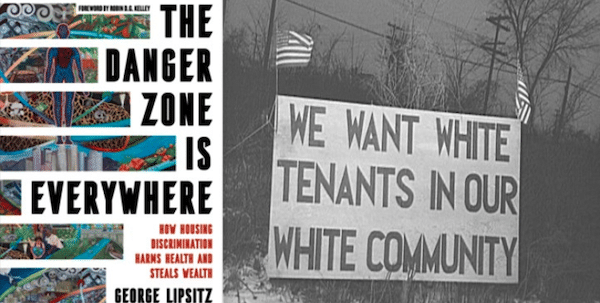

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is George Lipsitz. Lipsitz is Research Professor Emeritus of Black Studies and Sociology at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His book is The Danger Zone Is Everywhere: How Housing Discrimination Harms Health and Steals Wealth.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

George Lipsitz: The Danger Zone is Everywhere focuses on how unjust access to housing and health skews opportunities and life chances along racial lines. It argues that housing insecurity and poor health are key components of an unjust, destructive and deadly racial order. The book shows how the tort model of injury in law and the biomedical model of health work to occlude structural racism by treating socially produced injuries as personal problems.

Racist subordination is structural and systemic, not individual and aberrant. The rewards of whiteness are ingrained in the property system, protected by the law, and produced anew every day through a wide range of practices, policies, structures, and systems. Racial discrimination in access to housing and health care affects education, employment, policing, and access to assets that appreciate in value and can be passed down along generations. Racist subordination emanates from practices that may seem to have little direct relation or reference to race: from home value appraisals and tax assessments, municipal fines, fees, and debts along with incorporation and zoning policies, insurance industry redlining, privatization, predatory debt collection, and management of environmental crises.

RS: What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

GL: Activists and community organizers can join and promote the creation of an active engaged public sphere constituency for health and housing justice. The Danger Zone is Everywhere describes the victories won by fair housing councils, public health collectives, arts based restorative justice programs, community gardens, community land trusts, prison abolitionists, and a wide range of other autonomous action and learning circles.

Predatory disaster capitalism confronts us daily with new and horrifying crises—with murderous violence (both fast and slow), calculated cruelty, paroxysms filled with hate, hurt, and fear, and relentless acts of exploitation, domination, displacement, dispossession, and disrespect. It is strategically necessary and morally obligatory to stand up against unjust wars, predatory policing and mass incarceration, the rescinding of reproductive rights, transphobia and homophobia, anti-immigrant hatred, book banning and burning, and the ever renewing and expanding anti-Blackness at the center of bourgeois culture. But it is also important to see the train wrecks before they happen, to build cultures of mutual accountability, respect, and support that deepen collective capacities for accompaniment down the many different roads that can lead to social justice. Nobody can do everything but everybody can do something. As the motto of the Lavalas movement in Haiti in the 1990s stated “Alone we are weak, together we a cleaning flood.”

RS: We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping to dismantle?

GL: Dominant ways of knowing and being in this society pressure people to think of racism as individual, intentional, interpersonal and aberrant when it is actually collective, cumulative, constructed, and continuing inside structures and systems. In health care disproportionate emphasis on genetic codes obscures the significance of the zip codes where segregation concentrates poverty and illness. The Danger Zone argues that race is a political rather than a biological category, that multi-axis problems need intersectional solutions, and that color blind solutions can never solve color bound problems.

The tort model of injury in law and the biomedical model of health presume a satisfactory status quo interrupted by an injustice or illness. Within this framework, remedies are proposed after the fact of the injury in hopes of restoring the previous status quo. The tort model and the biomedical model imagine one cause that can be isolated and one effect that can be reversed. These frameworks are incapable of dealing with the ways in which the status quo of racial capitalism has never been satisfactory. Intergenerational injuries, dispossessions and traumas have no single starting point or end. Past injustices plague the present and prefigure an even worse future. We need to unlearn these models and replace them with practices shaped by precautionary principles that anticipate and prevent foreseeable harm.

RS: Which intellectuals and/or intellectual movements most inspire your work?

GL: During the past decade, masses in motion have taken to the streets and formed learning circles and activist oppositional campaigns in neighborhoods, schools, work places, professional organizations, and other voluntary groups that make up what scholars call civil society. Personally I have been educated, inspired, and activated by accompanying Building Healthy Communities in Boyle Heights (Los Angeles), Free-Dem Foundations (New Orleans), Asian Immigrant Women Advocates (Oakland), and the International Institute for Critical Studies in Improvisation (Guelph, Ontario). These groups build on, continue, and augment long histories of social justice struggle by the 1930s labor movement, the 1960s racial justice movements, and the late 20th century feminist, LGBTQ, and anti-corporate exploitation movements.

My understandings of ideas, evidence, and arguments owe much to conversations and collaborative work with Robin D.G. Kelley, Tricia Rose, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Luke Harris, Diane Fujino, Daniel HoSang, Ofelia Esparza, Rosanna Ahrens Esparza, Omar G, Ramirez, Quetzal Flores, Martha Gonzalez, RosaLinda Fregoso, Kalamu ya Salaam, Sunni Patterson, and Shana M. griffin.

RS: Which two books published in the last five years would you recommend to BAR readers? How do you envision engaging these titles in your future work?

GL: One of my discoveries in writing The Danger Zone is Everywhere has been to see how many great books are emerging in response to the systemic breakdown of racial capitalism that is unleashing conduct unfit for humans all around the world. There are too many great books for me to provide a complete list, but these six compel me to direct my future work toward connecting with the rising tide of social justice activism and providing whatever accompaniment I can to it:

- Tricia Rose, Metaracism

- Daniel HoSang, A Wider Type of Freedom

- Lorgia Garcia-Peña, Translating Blackness

- RosaLinda Fregoso, The Forde of Witness/Contra Feminicide

- Roderick Ferguson, One-Dimensional Queer

- Charles Briggs, Unlearning

Roberto Sirvent is the editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.