1. Introduction

The predominance of US economic, political and military power in the world was established at the end of the Second World War.1 With just 6.3 percent of global population, the United States held about 50 percent of the world wealth in 1948. As the only power which had used nuclear weapons on civilian targets, it demonstrated unchecked power and military might. The postwar world order was rebuilt with the United States at the core, including the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949 and Japan–US Security Treaty in 1951. The political order of major industrial powers, as well as some newly independent states which were key in the containment strategy during the Cold War, were shaped in the image of the United States as vehemently anti-Communist bulwark economies. But the global anti-war protests and US civil rights movement in the 1960s, along with the exhaustion of the postwar growth regime and the profitability crisis in the 1970s, led to the first crisis of US dominance in the postwar era.

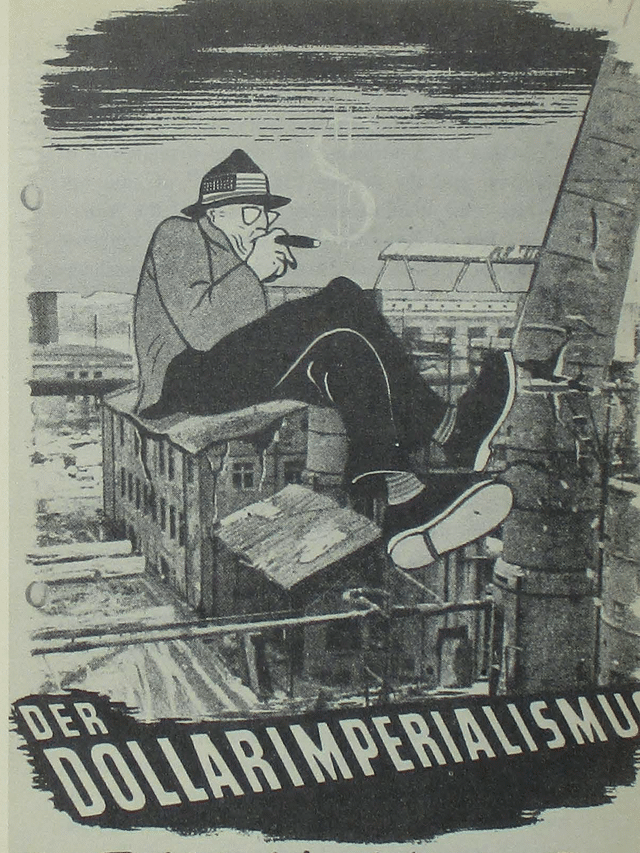

Neoliberalism was the US strategic response to the crisis. The subordination to neoliberalism of its industrial rivals in the global North and South through political and military power enabled the United States to reinforce its global dominance and built the dollar-Wall Street regime without addressing the roots of its economic decline (Gowan 1999). At home, through anti-labor legislation and divisive tactics, it broke the labor unions and dissolved working-class resistance to neoliberalism (Campbell 2005). The profitability of the US non-financial sector recovered from its lowest point of 12.7 percent in 1981 to 17.2 percent in 1997 (Roberts 2016, 22–25). The United States and its Western allies have maintained a near-monopoly in core technology and high value-added sectors in the global value chain. The reintegration of China into the world economy as a supplier of cheap resources and labor and a huge market for imported goods enabled the revitalization of some large Western non-financial enterprises, such as Boeing, General Motors, and Ford (Mahbubani 2020, 25–28). This golden era of US-led neoliberal globalization—a successful rebound from the crisis of US hegemony in the 1970s—lasted until China’s resistance to neoliberalism, most noticeably with its strong and competitive state sector, began to challenge its dominance from the 2010s and breach the comfort zone of the US and its allies.2

Neoliberal structural reforms in the republics of the former Soviet Union and in major industrial developing countries like Brazil and Mexico in Latin America from the 1980s signified a global paradigm shift from relatively equitable and productive development to financialized and polarizing development. The reforms facilitated the new international division of labor, in which the corporations based in the United States and allied countries dominate high value-added industries, such as design and market distribution, while those in the global South compete for outsourcing contracts in low value-added industries, often leading to a race to the bottom. The reserve currency status of US dollar and the expansion of finance capital in a liberalized and deregulated market allowed finance capital, mainly from the West, free rein to engage in speculative activities in almost any economy. The United States can externalize its deficit problems to the world through quantitative easing at times of its choosing, and has been able to maintain its primacy through political and military domination despite entering relative economic decline from the 1960s.

Yet the inherent contradictions of capitalism have deepened as US imperialism, built on suzerainty and seigniorage, has been unable to stop its economic decline: its share of value-added in manufacturing in high income countries fell from 78 percent in 2000 to 51 percent in 2021, while low and middle income countries’ share rose from 22 percent in 2004 to 48 percent in 2023. China’s share in the world total rose from 9 percent in 2004 to 29 percent in 2023, while the US fell from 25 percent in 2000 to 16 percent in 2021 (World Bank 2024). The coronavirus pandemic exacerbated the crisis of neoliberalism, as people came face-to-face with the human cost of the laissez-faire approach. The pandemic further exposed disparities between neoliberal and state-led approaches to public health. Many advanced economies suffered high death rates and falls in life expectancy as a result of underfunded public health systems and other social consequences following decades of neoliberal reforms and austerity. Meanwhile, without the capability to produce its own vaccines, the global South was left helpless in face of “vaccine imperialism” (Seretis et al. 2024).

The United States has increasingly relied on its military and political power rather than economic competitiveness to maintain world dominance. NATO expanded eastward and the US trade system in Asia strengthened, with renewed bilateral and multilateral treaties such as Trilateral Security Partnership (between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States), and the US-Japan-Korea Trilateral Pact. Over 730 US military overseas bases (Global South Insights 2024, 20; Johnson 2008, 139) serve as a deterrent to ideological challengers as well as to allies (Cumings, 2011). As its overall economic competitiveness declines, the Unites States increasingly relies on force to protect its leading position. In the post-pandemic era, the build-up of socioeconomic problems under neoliberalism is reaching a breaking point, which now extends to a crisis of confidence of the liberal democratic system.

In the face of the current crisis, the United States is reasserting dominance over its allies. Its role in the Ukraine-Russia conflict—from supporting the Maidan protests in 2014 to arming and funding Ukraine and sanctioning Russia and freezing its assets—has successfully weakened the European Union and pushed a realignment of the latter’s foreign and economic policies with the US. (Despite some disagreement with Trump on Russia, all the major EU powers plan to increase their defense budgets and their “loads” in NATO, meeting Trump’s demands.) Like the oil shocks of the 1970s, the ongoing war in Ukraine, combined with the cost of living crisis, has stalled any state-led attempt to break with neoliberalism and has deepened the reliance on finance capital. The prevalence of neoliberal ideology among the ruling elites and the threat of war have been effective in silencing opposition.

All this is a stark reminder to the rising China. While the United States cannot prevent its economic decline, it is resourceful in maintaining its imperialist regime. US imperialism encountered a similar predicament in the early 1970s, when it lost the Vietnam War but was able to rebound through political and military hegemony, giving rise to the dollar–Wall Street regime and a temporary revival of profitability. While under Trump the United States seems to be rejecting the neoliberal order at home and embracing explicit protectionism, neoliberalism as a global governing project has not receded.

2. US Imperialism in the 1970s: Crisis and Rebound

We have seen this before. The horrifying scenes of people fleeing war but with nowhere safe to go, the carpet bombing of the poorly equipped peoples who paying a high cost for defending themselves against invasion, the use of internationally banned weapons and genocidal tactics by the imperialist forces, a difficult if not impossible postwar reconstruction: this is Gaza today, and Vietnam during the US war in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

This imperialist aggression and unabashed brutality then sparked an international anti-war and anti-systemic movement in the 1960s. Apart from these protests, the economic competitiveness of US allies West Germany and Japan also put pressure on the United States as its economic situation worsened with rising military spending, slowing economic growth, and rising deficits. The US defeat in the Vietnam War also broke the myth of US military supremacy. In the face of profitability crisis and stagnation in the West, the United States abandoned dollar convertibility to gold in 1971 and unilaterally forced through a pure dollar standard in 1973, which deepened its credibility crisis (Gowan 1999). The sustainability of the US-led postwar liberal international order was seriously questioned. As Day (1995, pp. xv–xvi) writes, “By the early 1970s the financial institutions created after World War II were in disarray, and Soviet researchers advised Leonid Brezhnev that the forces of ‘peace and socialism’ had gained ascendancy in economic competition with the west.” Nixon’s pursuit of détente with Moscow in 1972 was a further sign of Soviet victory in the bipolar struggle.

However, despite economic pressures and military setbacks, the US successfully established the dollar–Wall Street regime against the opposition of its allies, who had instead proposed Special Drawing Rights instead of a pure dollar standard. They understood that under a dollar-dominated regime, the developments of Anglo-American financial markets and decisions by the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve would have overwhelming influence over other national currencies. It would give “Washington more leverage than ever at a time when American relative economic weight in the capitalist world had substantially declined” (Gowan 1999, 24). The United States was able to overcome this resistance by luring support from national finance capitals and using the influx of petrodollars to create American-centered private international financial markets, including offshore markets like City of London and Eurodollar markets, which rival with the traditional banking sector and draw in capitals from around the world, ultimately undermining states’ public financial regulations (Gowan 1999, 26–30).

With the maturing of a new political-military strategy following the Nixon Doctrine, which sought to draw China into the US orbit against the Soviet Union, the United States successfully ushered in the era of neoliberal globalization and reestablished the international division of labor during the global debt crisis, itself triggered by US interest rates hike (the so-called Volcker shock in 1979) and the defeat of organized labor in the West. The rate of profit in the US economy regained upward momentum in this period, until 1997 (Roberts 2016, 22–25). The new international monetary system incentivized economies holding dollar-denominated assets as foreign reserves to subsidize the US state through the purchase of US Treasury debts (to support the dollar against depreciation), in turn externalizing the risk of ongoing US balance-of-payment deficits. Contrary to Moscow’s expectation of a lasting peace after Nixon’s visit in 1972, Reagan sharpened the arms race with the Soviet Union and used this new financial strength to greatly expand funding to anti-Communist operations, including covert operations (for example, the US Army Human Terrain Teams, comprising social scientists who conducted “cultural” studies to collect and decode indigenous information for military purposes, while winning the “hearts and minds” of locals [Hevia 2012, 263]) and providing weapons to the mujahideen to fight Soviet forces in Afghanistan (Chomsky and Achcar 2007; US Department of State 1979).

The United States triumphantly ended the bipolar order and led the neoliberal offensive in the former Soviet Union and its allies. The postwar liberal international order was secured once again and expanded to new joiners like China and the East European countries. China’s entry into WTO in 2001 was seen as a total victory for the United States, as China would be subject to institutionalized US-led globalization and become another open market for transnational capital (Andreas 2008; Hart-Landsberg and Burkett 2005; Hung 2009).

3. Challenges to US Imperialism in the 21st Century

In the 21st century, especially after the Covid pandemic, American hegemony is again in serious crisis. This time, US economic decline is even more apparent and its main competitor, China, is catching up at an alarming rate. China is an enormous independent sovereign socialist state which is approaching the development level of the West in some key sectors. It is now bipartisan consensus in the United States that China’s rise must be stopped, along with its potential challenge to Western domination. The stakes are extremely high for the United States, as the PRC is much more powerful economically than the Soviet Union ever was, and its rise cannot be obstructed politically in the manner of client states such as Japan and South Korea3. The United States does not have military bases in mainland China. China is second to the United States in GDP and has even overtaken the United States as the largest economy in terms of purchasing power. China now stands equal with the US as a core player in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Dunford and Han 2025). If China’s lead in economic and productivity growth over the United States continues, it is only a matter of time until China replaces the United States as the world’s leading economic power (Ross 2024).

After the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997–98 and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–09, the huge socioeconomic costs associated with the dollar–Wall Street regime are fully exposed. The United States can easily bail out major US investors and financial institutions through quantitative easing and monetary policies, nicknamed as the “Federal Reserve put” (Desai 2023, 111). This creates an unequal playing field for other finance capitals, even if they share a common interest in financial deregulation and enlarged financial markets. As Desai argues, capitalist powers like Germany and Japan were readjusting their strategy to refocus on production4 and expand trade relations with China, until the outbreak of war in Ukraine in 2022 (Desai 2023, 103). Non-imperialist states, despite intertwining with the US-led international order and financial markets, are forced to compete for foreign investment based on economic performance, or at least to survive more frequent and recurring financial crises. While adhering to neoliberal doctrines, those with certain level of state capacity and industrial development would naturally be drawn to the China-centered productive base, which since 2010 has replaced the US as the largest manufacturing economy and has been the engine of global economic growth.

The civil war in eastern Ukraine expanded to a full-scale military conflict with Russia in 2022, after the failure of two Minsk agreements in 2014 and 2015. Despite the unprecedented level of military and economic support by the West to Ukraine, Russia has been able to hold its ground and even make advances. Russian recovery from decades of neoliberalization since the 1990s, and its superior military capabilities compared to the US military-industrial complex, show that its legacy as a contender during the Soviet era can still have an impact today, once the yoke of neoliberal ideology is broken.5 After the Hamas assault on October 7, 2023, Israel embarked an all-out invasion of Gaza and southern Lebanon, killing tens of thousands of people. Israel’s crimes—the use of internationally banned weapons, including bunker-busting bombs; heavy bombing of civilian areas such as schools, hospitals, and refugee camps; blocking supplies of food, water, and other essential aid; abusing captured Palestinians—have provoked worldwide condemnation and demands for peace and statehood for Palestine. All this stands in contrast with political and military support to Israel by the West.

How will the United States respond to the crisis? Would it be able to turn things around, as in the 1970s, by doubling down on political-military strategy? To answer these questions, we need to understand if the same rebound-facilitating conditions still exist in the current crisis.

Based on analysis of the three pillars of US hegemony—ideological/political, economic, and military—I argue that its erosion will continue despite the rise of US militarism. The United States’ control of its allies through the alliance of finance capitals and political influence may drive the remaining productive sector closer to China as a means of defending themselves from the aggressive, parasitic system led by the United States. The United States maintains a strong ideological grip through its elites and dominance in the media and the higher education sector. To develop a genuine alternative system, the global community must overcome the ideological and political obstacles installed by US imperialism, as economic competition alone will not be sufficient to shake its political-military bases. Nations need to address the superstructure of hegemony through a new global governance based on anticolonial, socialist values, no less than on economic and technological competition.

4. Erosion of the Economic Basis of US Hegemony

The United States still has strong political influence over its allies but does not wield absolute control. The US-led international financial institutions were the last resort for countries in distress in the 1980s, but today there are China-led financial institutions which can offer loans, often on better terms. With China as a practical alternative and US economic power in decline, the United States is struggling to enforce discipline on its subordinates through economic pressure alone. This is shown by Britain joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) despite US opposition, the reconciliation of Saudi Arabia, Iran, South Africa, and fourteen other countries accusing Israel of genocide in the war on Gaza (UN 2024), and the unsuccessful sanctions against Russian oil (FT 2023) etc.

In the 1980s, as the Soviet Union was forced to roll back assistance to developing countries due to socioeconomic constraints, credits from the US-led financial institutions became the last resort for countries in debt crisis. They were subject to the conditions set by these institutions and had to accept structural adjustment reforms required by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (see examples of “managed neo-liberalism” in Brazil and Mexico in Kiely, 2005, pp. 73–77). The interest rate hike to 20 percent imposed by the Federal Reserve Chair Paul Volcker in 1979 triggered a global debt crisis. Economic distress in developing countries was compounded by stagnation in the West, which led to a significant drop of export revenue in these countries (Saad-Filho 2006). Facing debt defaults, high-value assets were privatized and often sold at much discounted prices to foreign capitals. Domestic industrialization plans were dismantled and a colonial pattern of trade relations reestablished. Neoliberalism was brought in to aid this economic and social reengineering. The state capacity of the developing countries disintegrated under neoliberal reforms and democratization, representing a de facto political intervention against state-led development in the name of democracy (see South Korea for example in Song, 2013).

With the withdrawal of state-led productive investment, private and foreign investment was much needed for economic growth. Countries in the global South compete for outsourcing contracts from transnational corporations in the global North, driving a race to the bottom, while the debt-piling US market becomes a key export destination for most economies, including Germany and Japan, whose domestic consumption and productive investment has been curtailed by neoliberal reforms. Such a division of labor opens a growing gap between increasing productivity and weak demand on a global scale. By mandating neoliberal doctrines worldwide, the United States has successfully weakened its competitors and reasserted global dominance.

Nevertheless, as with US export financing to its allies during the Cold War to establish the supremacy of the dollar while also reindustrializing its competitors (Desai 2013, 97–99), the inclusion of China in its orbit has created unintended consequences for the United States: the rise of a competing mode of production, namely primitive socialist accumulation against capitalist accumulation (S.-K. Cheng 2023). Despite its integration into the neoliberal world system from 1978, China has been able to break the spell of deindustrialization or dependent industrialization and maintain strong state capacity (S. Wang, 2021).

China’s development thus presents an opportunity for the global South which simply did not exist in the 1980s. It is different from the bipolar order of the Cold War, for despite its historic achievement, the Soviet Union was not embedded in the world economy and did not have the financial resources that China has today. Trade within the Comecon region, among countries within the Soviet bloc, was outside the market mechanism and promoted specialization. By comparison, China-led financial institutions like the New Development Bank, the AIIB, the China Development Bank, and others are new international financiers able to compete with US-led international financial institutions and support national development projects. The advancement of technology such as electronic payments and digital currency provides feasible alternatives to the US financial system. The use of the PBOC’s Cross-Border Interbank Payments System (CIPS) is also growing rapidly, with transaction value up by 34 percent and transaction volume by 41 percent year over year by the end of 2023 (PBOC 2024). China’s own industrial upgrade has provided opportunities for developing economies. Contrary to imperialist countries in pursuing monopolized rent and super-profits in high-tech sectors, China’s sharply declining terms of trade (Lo 2020, 863–64), especially in capital goods, can facilitate industrial catch-up in relatively cash-strapped economies. According to a Lowy Institute report, by 2023 around 70 percent of economies (145 out of 205) traded with China more than with the United States, and 112 economies had more than twice as much trade with China than with the United States (Rajah and Albayrak 2025, 8).

The coexistence of the Chinese system and the US system in the capitalist world economy makes it possible for states to hedge against the risk of relying on just one, and for the Chinese system to act as a lifeline to those sanctioned by the United States (Eichengreen 2022). This fundamentally erodes the basis of the unipolar system, and makes it difficult for the United States to command absolute control of the world economy and the international financial system. The United States will have to rely more on extra-economic coercion to maintain its power6.

This process is still ongoing, but the fact that most countries, despite slow recovery or looming recession in the post-pandemic world economy, are able to stay afloat while the conditions of IMF loans remain largely the same (or even worse) shows that alternative funding may well have come to rescue. In fact, recent data have shown that between 2000 and 2021, China offered rescue lending totaling at least $240 billion to twenty countries: $170 billion in the form of the global swap line network led by the People’s Bank of China, $70 billion in bridge loans as balance of payments support, and commodity repayment facilities through Chinese state-owned enterprises in oil and gas (Horn et al. 2023, 3). These bailout lending programs have been crucial in helping many vulnerable states with low reserve ratios and weak credit ratings to overcome financial difficulties and avoid defaults.

The benefits of “hedging” are obvious even with states considered allies of the West. This is seen in Egypt, which receives large loans from the IMF but joined the BRICS in 2024. Egypt has been using the swap line drawdowns rollover in midst of ongoing IMF lending and a weak reserve position (Horn et al. 2023, 28). Turkey, a NATO member, also applied to join the BRICS bloc in 2024, and has used the renminbi swap lines to boost its gross reserves after depleting them to stabilize the lira (Horn et al. 2023, 31). The rise of China within US-led global capitalism is not a revolutionary challenge to the system, but nevertheless provides a credible and reliable alternative to the US-led economic order. The erosion of US hegemony is set to continue as the United States faces increasing difficulties in enforcing discipline through economic and financial means.

5. The Continuation of Ideological Hegemony

The ideological hegemony of neoliberalism is still strong, having dominated the mass media, civil society, and academic institutions for decades (E. Cheng and Lu 2021) but fast-changing contemporary developments, including the crisis of liberal democracy in the West, are challenging the dominant narrative. The accumulation of contradictions and polarization is reaching a breaking point in the United States, as political elites come to a bipartisan consensus that “the only way that they can assure the reproduction of the non-financial and financial corporations, their top managers and shareholders—and indeed top leaders of the major parties, closely connected with them—is to intervene politically in the asset markets and throughout the whole economy, so as to underwrite the upward re-distribution of wealth to them by directly political means.” (Brenner 2020). The fact that they can achieve upward redistribution of wealth in a “democratic” system in which the majority of people are guaranteed political rights, regardless of their economic status, shows the extent of ideological and cultural hegemony.

Decades of promotion of individualism, atomization, and laissez-faire have weakened the bases of organized, collective forces against capitalism and delegitimized non-neoliberal policies and practices. However, the inhumane nature and the huge social cost of neoliberalism have been fully exposed in the Covid pandemic, especially with the extremely high death rates in many advanced economies, including the United States. This contrasts sharply with the performance of China (Burki 2020; Tricontinental 2020) and other countries which do not fully embrace neoliberalism (Desai 2023, 129–35). The dearth of research and lack of interest in the evaluation of pandemic management among the media, academics, and civil society was another sign of the hegemony of ideology at play. When Western governments need to justify their return to the laissez-faire approach7 after a brief attempt to contain the spread of the virus, amid pressures from China’s state-led management, Western mainstream media and academics—rather than holding their own governments to accounts—dismissed the socialist value of China’s collective efforts, regarding the scientific approach to suppress and control infectious disease as just another example of the authoritarianism of the governing regime (Blanchette 2021; Wu et al. 2021; Zhou 2020).8

Compared to fierce economic competition, ideological competition with the US is almost nonexistent in China. Western institutions are still held in high esteem; their control of authoritative journals in liberal arts fields and high positions in university ranking tables are universally regarded as models of success (E. Cheng and Lu 2021). Fields that are crucial in constructing capitalist ideology—like sociology, history, economics, anthropology, and law—are often uncritically adopted in the global South, further internalizing imperialist ideology. The pro-imperialism nature of Western-modelled humanities and social sciences is succinctly summarized by Heller (2016, p. 171):

Universities during the Cold War produced a cornucopia of new positive knowledge in the sciences, engineering, and agriculture, but also in the social sciences and humanities, useful to business and government. In the case of the humanities and social sciences such knowledge, however real, was largely instrumental in character or tainted by ideological rationalization. It was not sufficiently grounded in history and tended to conceal or rationalize the question of class conflict and the drive of American imperialism overseas. Too much of it was used to control and manipulate ordinary people within and without the United States in behalf of the American state and the maintenance of the capitalist order. In the Gramscian sense it was part of the ideological state apparatus.

The impact doesn’t stop at ideological rationalization, but extends to the military/security front, for the ideological field is an essential part of contemporary US counterinsurgency operations. In his research of British empire-building in Asia, Hevia meticulously explains how military intelligence, based on social sciences, formed a crucial part of the security system for the British empire, not only in suppressing rebellions but also for long-term colonial governance. The United States has built a parallel system and even expanded it since the end of the Second World War, extending colonial governance without territorial conquests. Due to the scarcity of research in this field, Hevia’s study is extremely useful in helping us to understand the fusion of ideological and security power and monopoly capital, and is worth to quote at length:

Another feature of the American security regime that finds a corollary in the activities of the British in Asia is a continued commitment to the production of pertinent military, economic and political knowledge about the region. Critical to the development of such knowledge, after World War II, was the investment by the United States government and private foundations in area studies programs and the strategic social sciences (i.e., political science, sociology, psychology and anthropology) in American universities. The British has established something along these lines when the School for Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) was launched in 1916. However, the US initiative that began in the postwar period was much grander in scope than that of Britain in the earlier part of the century. Initial funding for the development of programs in foreign area studies was provided by the Ford, Rockefeller and Carnegie foundations. In 1950, Ford’s Foreign Area Fellowship, which was at first managed by the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies, helped to launch a variety of area centers located at major public and private universities across the United States. Eight years later, under Title VI of the National Defense Education Act (NDEA), the federal government began to provide funds for the sustenance and expansion of centers and research facilities, as well as for critical language programs. These programs built on links already established during World War II between universities and the state and closely followed wartime training and research programs.…Area studies research was useful for providing multifaceted, interdisciplinary pictures of the object under investigation and, within certain disciplines, specialists might also provide recommendations on policy and programs that could be useful in transforming the region or country in question (e.g., democratic nation-building in Japan, for example, under the auspices of the American occupation). (Hevia 2012, 258–59).

Apart from courses in social sciences, the study and application of operational systems based on managerial science and technologies of administration (using quantitative methods from physical sciences, mathematics and social sciences) become useful tools for security systems such as military simulations and guidance for interventions.9 As Hevia notes, “operational systems methodology…meshed neatly with the global expansion of American capitalism and military bases, providing a vast tool kit of techniques for organizing the planning, deployment, and logistics of the American security regime” (Hevia 2012, 259). The rise of the color revolutions around the world, including the anti-China movement in Hong Kong in 2019, shows that the combination of ideological hegemony and operational systems could effect regime change even without the deployment of US armed forces.

As pointed out by Vukovich (2020, p. 14), “Hong Kong’s universities, public schools, and media outlets…have been the main sites of liberal democratic hegemony since the 1997 handover”. In the field of political science, it is regarded as a point of almost papal infallibility that China is an undemocratic, authoritarian, autocratic system, a premise from which many political science and governance studies begin. On the mainland—albeit on a different scale, and with some development of counter-ideology—Western ideology, whether in the form of comprehensive neoliberal culture or Keynesian economics (similar to Rostow’s modernization theory, “a non-communist manifesto”), uncritical of imperialism, has been systematically reproduced, marginalizing or silencing criticisms of US imperialism. Other global South countries with no alternative (socialist) values system to capitalism are even more defenseless. The United States continues to be the main training ground for global South elites, and has expanded its web of ideological influence through well-funded open and covert operation. In 2024, the Congress passed the H.R. 1157 to authorize more than $1.6 billion in five years as the Countering the PRC Malign Influence Fund (GT 2024).

Many think tanks and media outlets are privately owned and share capitalist values. Trained professionals often operate within the confines of US ideological hegemony. Those who dare to challenge the regime have to pay a very high price and are often isolated by their peers, as seen in the case of Julian Assange. The cultural and ideological dominance of the United States dominates the profession and is backed up by physical coercion. But a recent Pew survey has shown a decline in confidence and satisfaction in the democratic system across high-income countries (Fetterolf and Wike 2024). The rise of discontent with the liberal democratic system is clear (Pilon 2017). But whether the discontent will be channeled toward socialist forces for systemic change is unknown, and with a consistent history of lack of revolutionary leadership on the left and the secular decline of the working class in the imperialist countries, hope for change may more likely lie in the global South.

China’s call for a new global governance framework—including the Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative, and Global Civilization Initiative—with the aim to build a global community with a shared future, can be useful for developing a contending ideology to US imperialism. But for the initiatives to effect systemic changes, it must be accompanied by the rise of class politics in struggles against imperialism.

6. Counter-developments to the US Parasitic System

The alliance of national finance capital with US capital deepens at times of crisis, as in the case of Japan and the European Union (Gowan 1999, 126–31; Sato 2018). Weakened industrial sectors in the European Union prop up pro-US elements and push the block further towards confrontation with US-designated threats. However, the dominance of finance capital will increasingly alienate the majority of people, destabilizing the capitalist system as a whole, as social polarization reaches an extreme level, with a shrinking middle class (Eurofound 2024; Kochhar 2024) and rising destitution in advanced economies (NIESR 2021; Rank 2024). As Gowan remarked after the Asian Financial Crisis, neoliberal globalization led by the United States has shrunk into a “narrow ideology of rentiers and speculators,” who despite remaining extremely powerful, “have lost the capacity to present themselves as the bearers of any modernization program for the planet” (Gowan 1999, 131).

The breakdown of the postwar liberal international order and the fracturing of the world economy—partly thanks to US and EU confiscation of Russian foreign assets and aggressive US protectionism and techno-nationalism10 against China and its allies—is forcing national capitals to rethink their strategies. Some, like Germany, may try to limit the damage in the unstable, corrosive, and potentially ruinous US-led international order, despite seeing China as the main systemic challenge to its “rules-based” order in the long-term. There is evidence of a lukewarm or even muted response in US Asian allies Japan and South Korea toward the US Huawei ban (Lee, Han, and Zhu 2022). Germany openly opposed EU tariffs on Chinese-made electrical vehicles, although it was unable to overturn the decision (Politico 2024).

While financial profits are taking a bigger share of overall profits, in reality, finance capital cannot replace non-financial production completely, as surplus value is only created through production, not exchange. The marginalization and politicization of industrial investments by financial interest, in addition to the prohibitive environment for productive investment, including the sharp rise of energy costs and the decline of manpower, may drive industrial investment closer to China, an economy with unparalleled supply chains and an expanding consumer market. The pull and push elements may expediate the relocation of more productive industries to China: a prime example is BASF, the largest chemical company in Europe, which is expanding production in China while closing down plants in Germany (BASF 2024).

The decaying, parasitic stage of capitalism has intensified the dictatorship of finance capital in all capitalist countries. The international alliance of finance capitals forms a network of bourgeois states supporting US political-military strategy, which are increasingly dependent on their security systems to quell dissent. But US allies also find it difficult to contain their discontent and are coping with the consequences of economic suicide and political-military dependency on the United States. While the United States seems able to use political and military hegemony to reassert its dominance over its allies, the hollowing of its economic base will only hasten the decline of US imperialism.

The contradictions of capitalism are only increasing. The unsustainability of the US-led global order is also demonstrated in climate emergencies; the expropriation of nature (and humanity) for capitalist accumulation is reaching an exhaustive point. China’s success in green development, an exception to the current global trend, shows that technological and productivity growth can indeed become the basis for a global ecological civilization (Foster 2022).

The Chinese state’s doubling down in developing qualitatively new productive forces—and as a result, cheapening prices of a wide range of industrial goods—has had a positive impact by bringing down overall production costs for essential products for sustainable development, and by improving living standards for most people (Dunford 2024, 58). China’s push to remove barriers for foreign investment and invest in infrastructure is set to draw in productive capital and strengthen a united front of resistance to financialization. In the words of Dilma Rousseff, the President of New Development Bank,

The rules and practices of international trade and finance are being broken and fragmented. The use of sanctions as a weapon, technological embargoes, and the intensification of localized conflicts create obstacles to stability, peace, economic growth, and deepen social inequalities.

These crises represent significant risks to the prosperity of all peoples. When not adequately addressed, they exacerbate political polarization, and as a result, the global economy runs the risk of fragmenting, consumed by protectionism. And, as we know from history, economic protectionism serves only the hegemony of a few powerful players, relegating developing countries and emerging economies to the periphery of an unequal system that concentrates wealth and power.

Climate emergencies are worsening and affecting all continents with increasingly devastating effects. The Global South has made significant efforts to address this multitude of crises through cooperation and the construction of sustainable, inclusive, and resilient multilateralism.

The Belt and Road Initiative is conceived to address these challenges and transform them in an opportunity to put in place the biggest cooperation platform among countries. (NDB 2023)

The success of Chinese initiatives in forming a global counter-development to US imperialism will depend on the timely emergence of popular national forces in the rest of the world capable of addressing the legacies of neoliberalism in their own countries and negotiating the effective use of Chinese investments.

7. Conclusion

US imperialism is once again in crisis, but the conditions for its future rebound, if the latter is even possible, have changed. While the ideological hegemony of neoliberalism and the alliance of finance capital remain strong, the unsustainability of the US-led system is becoming common sense. The crisis of liberal democracy and the breakdown of the postwar international order are signs of US imperialism in crisis, even as a strong systemic challenge has yet to form. China’s financial and technical assistance to developing countries may not replace the American system, but nonetheless provides a valuable and practical alternative to states seeking to break from the neoliberal path. Global South countries are realigning with Beijing on some global issues (e.g., the BRICS Summit on Gaza, the visit to Beijing by leaders of Arabic and Islamic states, and the signing of the Beijing Declaration on Ending the Divide and Strengthening Palestinian National Unity by fourteen Palestinian political organizations). Whether this realignment will lead states to leave the US security system likewise depends on the rise of anti-imperialist counterforces.

China’s call for a new global governance framework, based on the UN Charter and productive investments, provides an opportunity to anti-neoliberal and developmental forces, which may give rise to a new international economic order. However, it must be stressed that the US experienced a similar situation in the 1970s and was able to rebound with political-military strategy despite secular economic decline. Counter-development to US imperialism cannot only rely on the economic front, but more importantly, must act on the political front. Take China as an example: its ability to continue and deepen its alternative development in face of mounting US pressure is due to its break from imperialism after a successful socialist revolution. The value and implications of China’s political economy for the global South are hence not just in its economic achievement, but its ongoing political struggle against imperialism, despite all odds.

Bibliography

Andreas, Joel. 2008. “Changing Colors in China.” New Left Review II, no. 54 (December), 123–42.

BASF. 2024. “Our Engagement in China.” 2024. https://www.basf.com/basf/www/bd/en/who-we-are/organization/locations/asia-pacific/our-engagement-in-china.

Blanchette, Jude. 2021. “Xi’s Gamble.” Foreign Affairs, August 2021.

Brenner, Robert. 2020. Escalating Plunder.” New Left Review, no. 123 (June). https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii123/articles/robert-brenner-escalating-plunder.

Burki, Talha. 2020. “China’s Successful Control of COVID-19.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 20 (11): 1240–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30800-8.

Campbell, Al. 2005. “The Birth of Neoliberalism in the United States: A Reorganization of Capitalism.” In Neoliberalism: A Critical Reader, edited by Alfredo Saad-Filho and Deborah Johnston, 187–98. London, UNITED KINGDOM: Pluto Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/umac/detail.action?docID=3386182.

Cheng, Enfu, and Baolin Lu. 2021. “Five Characteristics of Neoimperialism.” Monthly Review 73, no. 1 (May 2021). https://monthlyreview.org/2021/05/01/five-characteristics-of-neoimperialism/.

Cheng, Sam-Kee. 2023. “Catching-up and Pulling Ahead: The Role of China’s Revolutions in Its Quest to Escape Dependency and Achieve National Independence.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 53 (5): 789–809. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2023.2222410.

Chomsky, Noam, and Gilbert Achcar. 2007. Perilous Power: The Middle East & U.S. Foreign Policy : Dialogues on Terror, Democracy, War, and Justice. Edited by Stephen Rosskamm Shalom. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Cumings, Bruce. 2011. “The ‘Rise of China’?” In Radicalism, Revolution, and Reform in Modern China: Essays in Honor of Maurice Meisner, edited by Catherine Lynch, Robert B. Marks, and Paul G. Pickowicz, 185–208. Blue Ridge Summit, Lexington Books/Fortress Academic. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/umac/detail.action?docID=718683.

Day, Richard B. 1995. Cold War Capitalism: The View from Moscow, 1945-1975. London: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Cold-War-Capitalism-The-View-from-Moscow-1945-1975-The-View-from-Moscow-1945-1975/Day/p/book/9781563246616.

De Crescenzio, Annamaria, and Etienne Lepers. 2024. “Extreme Capital Flow Episodes from the Global Financial Crisis to COVID-19: An Exploration with Monthly Data.” Open Economies Review, April. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-023-09745-2.

Desai, Radhika. 2013. Geopolitical Economy After US Hegemony, Globalization and Empire. The Future of World Capitalism. London: Pluto.

———. 2023. Capitalism, Coronavirus and War: A Geopolitical Economy. 1st ed. Rethinking Globalizations. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003200000.

Dunford, Michael. 2024. “On Qualitatively New Productive Forces and Their Advantages for China.” World Marxist Review 3 (3): 53–62. https://doi.org/10.62834/a64nce35.

Dunford, Michael, and Mengyao Han. 2025. “Energy Dilemmas: Climate Change, Creative Destruction and Inclusive Carbon-Neutral Modernization Path Transitions.” International Critical Thought, January, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/21598282.2025.2448920.

Eichengreen, Barry. 2022. “Sanctions, SWIFT, and China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payments System.” CSIS Briefs, May.

Eurofound. 2024. “Developments in Income Inequality and the Middle Class in the EU.” Luxembourg: Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2806/477653.

Fetterolf, Janell, and Richard Wike. 2024. “Satisfaction with Democracy Has Declined in Recent Years in High-Income Nations.” Pew Research Center, 18 June 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2024/06/18/satisfaction-with-democracy-has-declined-in-recent-years-in-high-income-nations/.

Foster, John Bellamy. 2022. “Ecological Civilization, Ecological Revolution: An Ecological Marxist Perspective.” Monthly Review 74, no. 5 (October 2022). https://monthlyreview.org/2022/10/01/ecological-civilization-ecological-revolution/.

FT. 2023. “The West’s Russia Oil Ban, One Year On.” Financial Times, December 9, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/69d83a44-1feb-4d6b-865d-9fb827b85578.

Global South Insights. 2024. “Hyper-Imperialism: A Dangerous Decadent New Stage.” Studies/Contemporary Dilemmas 4. Tricontinental. https://thetricontinental.org/studies-on-contemporary-dilemmas-4-hyper-imperialism/.

Gowan, Peter. 1999. The Global Gamble: Washington’s Faustian Bid for World Dominance. 1st ed. London: Verso.

GT. 2024. “GT Investigates: What US’ Inglorious $1.6B Anti-China Info Campaign Budget Is about and Where the Money Goes – Global Times.” Global Times. 29 September 2024. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202409/1320583.shtml.

Hart-Landsberg, Martin, and Paul Burkett. 2005. China and Socialism: Market Reforms and Class Struggle. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Heller, Henry. 2016. The Capitalist University: The Transformations of Higher Education in the United States Since 1945. London: Pluto.

Hevia, James Louis. 2012. The Imperial Security State: British Colonial Knowledge and Empire-Building in Asia. Critical Perspectives on Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Horn, Sebastian, Bradley C. Parks, Carmen M Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch. 2023. “China as an International Lender of Last Resort.” Kiel Working Paper, no. 2244 (March).

Hung, Ho-fung. 2009. “America’s Head Servant?” New Left Review II, no. 60 (December), 5–25.

Johnson, Chalmers A. 2008. Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic. New York: Holt.

Kiely, Ray. 2005. The Clash of Globalizations: Neo-Liberalism, the Third Way and Anti-Globalization. 1st ed. Vol. 8. Historical Materialism Book Series. Boston: Brill.

Kochhar, Rakesh. 2024. “The State of the American Middle Class.” Pew Research Center (blog). May 31, 2024. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2024/05/31/the-state-of-the-american-middle-class/.

Lee, Ji-Young, Eugeniu Han, and Keren Zhu. 2022. “Decoupling from China: How U.S. Asian Allies Responded to the Huawei Ban.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 76 (5): 486–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/10357718.2021.2016611.

Lo, Dic. 2020. “Towards a Conception of the Systemic Impact of China on Late Development.” Third World Quarterly 41 (5): 860–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1723076.

Luckey, David, Bradley M. Knopp, Sasha Romanosky, Amanda Wicker, David Stebbins, Cortney Weinbaum, Sunny D. Bhatt, Hilary Reininger, Yousuf Abdelfatah, and Sarah Heintz. 2021. “Measuring Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Effectiveness at the United States Central Command.” RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR4360.html.

Luo, Yadong, and Ari Van Assche. 2023. “The Rise of Techno-Geopolitical Uncertainty: Implications of the United States CHIPS and Science Act.” Journal of International Business Studies 54 (8): 1423–40. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-023-00620-3.

Mahbubani, Kishore. 2020. Has China Won? The Chinese Challenge to American Primacy. First edition. New York: PublicAffairs.

NDB. 2023. “Speech by the NDB President Mrs. Dilma Rousseff, at the Third Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation, Beijing, China, October 18, 2023.” New Development Bank (blog). 23 October 2023. https://www.ndb.int/insights/speech-by-the-ndb-president-mrs-dilma-rousseff-at-the-third-belt-and-road-forum-for-international-cooperation-beijing-china-october-18-2023/.

NIESR. 2021. “Press Release: Destitution Levels Are Rising across the Country – and Terribly Worrying in Certain Regions, NIESR Research Shows.” National Institute of Economic and Social Research. 22 February 2021. https://www.niesr.ac.uk/news/niesr-press-release-destitution-levels-are-rising-across-country-and-terribly-worrying-certain-regions-niesr-research-shows.

PBOC. 2024. “People’s Bank of China Payment System Report (Q4 2023).” People’s Bank of China. http://www.pbc.gov.cn/en/3688110/3688259/3689026/3706133/4756451/5331145/2024041710323733841.pdf.

Pilon, Dennis. 2017. “The Struggle Over Actually Existing Democracy.” In Rethinking Democracy, edited by Leo Panitch and Greg Albo, 1–27. Socialist Register 2018. New York: Monthly Review Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1pwt8df.5.

Politico. 2024. “EU Countries Overcome German Resistance to Back Duties on Chinese EVs.” POLITICO, October 4, 2024. https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-countries-clear-way-for-duties-on-chinese-evs/.

Rajah, Roland, and Ahmed Albayrak. 2025. “China versus America on Global Trade.” Lowy Institute Indo-Pacific Development Centre.

Rank, Mark Robert. 2024. “Official US Poverty Rate Declined in 2023, but More People Faced Economic Hardship.” The Conversation. September 10, 2024. http://theconversation.com/official-us-poverty-rate-declined-in-2023-but-more-people-faced-economic-hardship-238520.

Roberts, Michael. 2016. The Long Depression. Chicago: Haymarket.

Ross, John. 2024. “China’s Economy Is Still Far Out Growing the U.S. – Contrary to Western Media ‘Fake News.’” MR Online. February 27, 2024. https://mronline.org/2024/02/27/chinas-economy-is-still-far-out-growing-the-us-contrary-to-western-media-fake-news/.

Saad-Filho, Alfredo. 2006. “The Rise and Decline of Latin American Structuralism and Dependency Theory.” In Origins of Development Economics: How Schools of Economic Thought Addressed Development, edited by Jomo K.S, 128–43. New Delhi: Zed.

Sato, Takuya. 2018. “Japan’s ‘Lost’ Two Decades: A Marxist Analysis of Prolonged Capitalist Stagnation.” In World in Crisis: A Global Analysis of Marx’s Law of Profitability, edited by Guglielmo Carchedi and Michael Roberts, 157–82. Chicago: Haymarket.

Seretis, Stergios A., Stavros D. Mavroudeas, Feride Aksu Tanık, Alexios Benos, and Elias Kondilis. 2024. “COVID-19 Pandemic and Vaccine Imperialism.” Review of Radical Political Economics, October, 04866134241282107. https://doi.org/10.1177/04866134241282107.

Song, Hae Yung. 2013. “Democracy against Labor: The Dialectic of Democratization and De-Democratization in Korea.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 43 (2): 338–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2012.759684.

Tricontinental. 2020. “China and CoronaShock’. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.” 28 April 2020. https://thetricontinental.org/studies-2-coronavirus/.

UN. 2024. “South Africa vs Israel: 14 Other Countries Intend to Join the ICJ Case.” United Nations Western Europe. October 30, 2024. https://unric.org/en/south-africa-vs-israel-14-other-countries-intend-to-join-the-icj-case/.

US Department of State. 1979. “Foreign Relations of the United States, 1977-1980, Volume XII, Afghanistan, Document 76.” Office of the Historian. October 23, 1979. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1977-80v12/d76.

Vukovich, Daniel. 2020. “A City and a SAR on Fire: As If Everything and Nothing Changes.” Critical Asian Studies 52 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14672715.2020.1703296.

Wang, Shaoguang. 2021. China’s Rise and Its Global Implications. 1st ed. Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4341-5.

World Bank. 2024. “World Bank Open Data.” World Bank Open Data. August 12, 2024. https://data.worldbank.org.

Wu, Cary, Zhilei Shi, Rima Wilkes, Jiaji Wu, Zhiwen Gong, Nengkun He, Zang Xiao, et al. 2021. “Chinese Citizen Satisfaction with Government Performance during COVID-19.” Journal of Contemporary China 30 (132): 930–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2021.1893558.

Zhou, Xueguang. 2020. “Organizational Response to COVID-19 Crisis: Reflections on the Chinese Bureaucracy and Its Resilience.” Management and Organization Review 16 (3): 473–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2020.29.

Notes

1. I would like to thank Professor Michael Dunford for reading the manuscript and giving me very helpful comments, which I have incorporated in the revised version. I would also like to thank Professor Cheng Enfu and Mr. Cem Kizilcec for reading the revised manuscript and for their generous comments. This article is a product of the numerous discussions and collaborative research with Mr. Gu Mingong on Asian politics and US imperialism. I am obliged to his generous assistance and constructive comments.

2. Here I use the term hegemony to depict the US-dominated world order. US preeminence was established at the end of the Second World War and further strengthened after the fall of the Soviet Union, but this does not mean that its position has remained unchallenged or that a stable hegemonic system is in place. Desai (2013, 2023) explains the dialectical development by which the US has inadvertently facilitated the formation of counter-development with its response to challenges to its hegemonic project, due to the inherent contradictions of capitalism. The United States has been the dominant power since the end of the Second World War, but it cannot stop contender states from emerging.

3. In light of increasing pressures from the United States, including banning of certain Chinese companies from the US market, China has not reached agreement with the United States, as Japan did in the mid-1980s with, for example, the US-Japan semiconductor trade agreement, in which Japan accepted voluntary reduction of semiconductor exports to the United States and to help secure 20 percent of their domestic market for foreign producers within five years (Irwin, 1996, p. 5), and the Plaza Accord, which led to the rapid appreciation of yens and Japan’s asset bubble (McCormack, 2007).

4. According to OECD monthly capital flow data, equity inflows to the US since 2008 have been negative. The net capital inflows to the US since 2008 are mainly from debt inflows and portfolio inflows (De Crescenzio and Lepers 2024).

5. I would like to thank Professor Michael Dunford for this insight.

6. See the detailed report on rising US militarism, labelled as hyper-imperialism, by Global South Institute (Global South Insights 2024).

7. See the detailed report of such developments in the US and Europe in Desai, 2023, pp. 130–137.

8. As concluded in the Report of the WHO–China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019, “as the outbreak evolved, and knowledge was gained, a science and risk-based approach was taken to tailor implementation. Specific containment measures were adjusted to the provincial, county and even community context, the capacity of the setting, and the nature of novel coronavirus transmission there” (cited in Desai, 2023, p. 130).

9. Influential think tanks like the RAND Corporation adopt this methodology. See their report (Luckey et al. 2021), coauthored with U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) Directorate of Intelligence, on measuring the effectiveness of its intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operations, for example.

10. The US CHIPS and Science Act, introduced in 2022, includes market-distorting and pro-subsidy industrial policies, investment-screening regimes, export controls, and weaponization of global value chains to apply political alliance to economic sphere (Luo and Van Assche 2023).