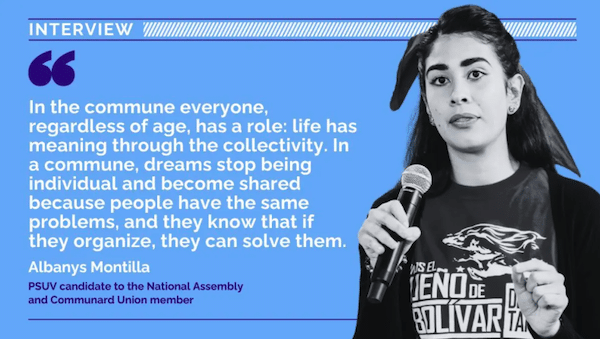

Albanys Montilla is a 27-year-old communard from rural Trujillo state. Born into a working-class family deeply committed to the Bolivarian Revolution, she became politicized early in life through grassroots organizing, witnessing firsthand the struggles of Venezuela’s campesinos. Now a PSUV candidate for the National Assembly, Montilla sees the parliament as a space to develop laws that further empower the country’s communes.

In this interview, Montilla discusses the political formation of her generation, the role of women in sustaining the Bolivarian Process, and the recent re-centering of the commune as a cornerstone of revolutionary politics. For Montilla, the commune is not merely a structure of popular power—it is the seedbed for a new collective consciousness and a transformative way of life that is being built from below.

Cira Pascual Marquina: You’re one of the youngest PSUV candidates, and you have a longstanding engagement with the communal project. Can you tell us about your background as a young person who grew up politically in a time of intensified imperialist aggression?

Albanys Montilla: How and where I grew up shaped everything. I’m not from the city. I’m from rural Venezuela, from a small Andean town called Carache. I was born to a politicized working-class family: my mother is a teacher and my father is a campesino. My mom is a diehard Chavista, and she always jokes that she dedicated her life to building communal councils, while I have committed myself to the commune. We represent two generations, but ours is ultimately the same project. Our story reflects how struggles can be inherited in a revolutionary context like Venezuela’s. I have a big debt to my mom.

She organized assemblies, met with campesinos, and promoted discussions on how to organize production. I went and I listened: they didn’t just talk about overcoming the exploitative practices that they endured. Their main goal was to organize the community, build a collective, and promote humanly meaningful processes.

But I also grew up seeing how the system exploits campesinos, how they get paid a pittance for their production, how they have no pensions, how they lack the tools they need to produce more efficiently. All of that shaped my political consciousness from a very early age.

Then, when I was in high school and was trying to decide what to study, Comandante Chávez passed away, and all hell broke loose. That’s when the economic war against the working people of Venezuela began, which was followed by the imposition of unilateral coercive measures by U.S. imperialism. They had one intention: to demoralize the pueblo so that they would, in turn, overthrow its government. They haven’t succeeded, but the harm they’ve done is enormous.

Suddenly, people who used to live with dignity, living wages, scholarships, and public transport, found themselves in long lines just to buy basic food goods. For women, the situation was particularly hard. Women are the backbone of this revolution—we’re the ones who do the door-to-door visits, organize assemblies, ensure that the gas cylinder arrives at each household, and organize censuses to make sure government programs get to every corner of the barrio. But women are also the ones who care for the family and are often the providers, so when the economic war was unleashed against us, women were the ones who had to confront not only the long lines to acquire cornflour very long, but also that there were no medicines, no contraceptives, no sanitary pads, etc.

That kind of hardship impacts people’s political consciousness, particularly among the youth. Consciousness doesn’t remain fixed. Our revolution made huge strides in popular education—we eradicated illiteracy thanks to cooperation with Cuba, and we sent people abroad for training. But the economic war chipped away at all that. And, at the same time, there was a new generation that had never heard “Aló Presidente,” that didn’t grow up with Chávez’s mass pedagogy.

Chávez would read Gramsci, Marx, and talk about Bolívar. He explained their ideas in simple terms, linking them to our everyday struggles. That shaped political consciousness across all sectors—workers, campesinos, barrio dwellers, and even the middle class. With his passing and the economic crisis, a new generation emerged with an undefined political horizon. Many began to associate the Revolution with hunger and hardship, and not a small number left the country.

We now have a new generation that, in many cases, grew up without their parents because they had migrated. Families were torn apart. The psychological toll of this isn’t much talked about. Youth is not another sector—it’s a biological stage when you are shaping your understanding of the world. Then, there is an added hurdle now: young people are also shaped by social media, which imposes a distorted, individualist, and consumerist worldview.

You have kids going out into the world, poisoned by what they’ve seen on their phones, full of resentment. They’re disconnected from the reality around them, even when a communal council is operating in their barrio. The private sector offers precarious jobs with no security. And on top of that, the culture pushed by influencers—people traveling, dressing fashionably, consuming nonstop—fuels a sense of lack and despair.

As I said before, I grew up in a working-class family that was politicized, but much of my generation doesn’t understand that there are underlying class contradictions and an external aggression. Even if the government designs coherent public policies, the capitalist system imposes obstacles every day. Those are the challenges my generation faces.

CPM: In the more robust communes, the youth have a different vision of the world and a stronger political identification with the Chavista project. What role does the commune play in building a different kind of consciousness?

AM: One of the most important things about the commune is that everyone, regardless of age, has a role. Everyone has responsibilities: life has meaning through the collectivity. In a commune, dreams stop being individual and become shared because people have the same problems, and they know that if they organize, they can solve them.

In a territory where the commune is real, where it is active, there’s a social and political fabric that gives everyone a purpose. If someone isn’t yet involved, the collective calls on them to participate. That demand makes you feel part of something. It creates a healthy society.

For this reason, the youth who grew up in robust communes have a different worldview.

A popular consultation assembly. (Ministry of Communes)

CPM: Recently, the government has put the commune back at the center of the political process. What’s your take on this?

AM: I think this is a crucial moment and a beautiful one too. People often quote Chávez’s “Golpe de Timón” [“Strike at the Helm“] as a turning point, as a moment when the Comandante told ministers that perhaps the Ministry of Communes should be eliminated because building communes was everyone’s job—every minister had to commit.

That was a radical moment because Chávez made it clear that the commune is not just another sector; it’s the cornerstone of the Revolution. Now we’re living another “Golpe de Timón,” this time with President Nicolás Maduro at the helm.

This isn’t just rhetoric: the entire cabinet is now focused on the communal project, as Chávez demanded. More importantly, concrete mechanisms have been set in place to activate communal life, including popular consultations. In those processes, people meet in assemblies, talk about their vision of the commune—how they see themselves now, how they imagine the future, what problems they face, and how to solve them collectively—they vote on projects, and execute them without mediation.

Communes and communal circuits [communes-to-be] receive resources directly; state funding doesn’t go to mayors or governors, but to communal banks. Communal banks are not traditional financial institutions, they are mechanisms for the people to manage their own resources. This changes everything. Now people are not bound to making demands or requests to a representative who never went back to the barrio after the elections. It’s your neighbor, someone who shares your reality and is accountable to you, who runs the communal bank with collective supervision. Additionally, with the consultations, resources stretch further because the labor is provided by the community itself.

The consultations are one of the most radical things we’ve done. Popular consultations are real participatory democracy.

CPM: You’re a candidate for the National Assembly. In your view, what role should the parliament play in this historical moment?

AM: The National Assembly is our country’s legislative branch. When it was taken over by the opposition in 2015, we saw how they used it to encourage imperialist attacks against the Venezuelan economy. They also tried to infiltrate the state, not precisely to improve people’s lives, but to seize power and control Venezuela’s resources.

The pueblo, not government officials, suffered a lot, even though the imperialist media said that the sanctions targeted the government. We lost access to food, medicines, and basic services. That’s why it’s so important that candidates coming from the pueblo take on roles of representation. We need laws focused on the people’s real needs, and we also need to project the voice of the communes in the National Assembly.

We have some important progressive laws, but we also have many that are outdated. For instance, with the current growth of urban and rural communes, we need a legal framework that supports the real development of the communal economy.

Imagine if communes could exchange goods not just within Venezuela, bypassing intermediaries, but also internationally—within Latin America. That was the dream of ALBA, and we can bring it back through laws rooted in popular power.

CPM: The upcoming elections are crucial because, as you say, we are in the era of communes. What are your hopes, as a young working-class woman and a communard, at this moment?

AM: I hope that the new National Assembly will help us strengthen the communal path towards socialism. “Commune or Nothing” is not just a slogan; it’s becoming a reality across the country. The commune is not just a sum of instances such as the communal parliament, the committees, and the communal bank. The commune is a new way of life that we are collectively building from the ground up.

People have long questioned the institutional management of resources because of inefficiency. Now, however, in every corner of Venezuela, people in the communes are organizing to make sure those resources reach them directly. As opposed to liberal democracy mechanisms, which put all the stakes on one representative, democracy in the commune is about everyone. In the new National Assembly, we should focus on making communes stronger.

Grassroots organization is the only guarantee we have for a better life—one in which we can dream individually but fulfill those dreams through collective action.