On July 27, Venezuela will hold mayoral elections nationwide. Here we talk to a candidate in the running to become mayor of Urachiche, a municipality in Yaracuy state with a population of about 22,000. Lisbed Carolina Parada is a long-time communal organizer and founding member of the Alí Primera Commune, who is making her bid with the backing of the Patriotic Pole. Parada represents a new generation of grassroots leaders seeking to forge links between municipal governments and communal power. In this interview, she reflects on her political trajectory, the challenges of institutional politics, and her vision for building a communal city with the help of the local government.

[You can read an in-depth testimonial series centered on two of the three communes in the Urachiche municipality here.]

Cira Pascual Marquina: In an earlier interview, you mentioned that the Alí Primera Commune of Urachiche was built little by little through a collective effort. As someone who participated in its making, how did that experience shape your ideas about how to govern as mayor of Urachiche?

Lisbed Carolina Parada: I was born in 1986, just a few years before the popular uprising known as the Caracazo [1989] and Chávez’s 1992 rebellion. At that time, the fight for the land was getting more intense in our town. That struggle was formative for me.

Chávez came to power when I was still a teenager, and his presidency fueled deep hopes. The Comandante stood up for the people’s right to the land. For that reason, the long-lasting struggle to redistribute the land of three large estates in the lowlands of Urachiche became even stronger during the early years of his presidency. These estates were San Simón, Bellavista, and Aracal, and they were controlled by exploitative landlords.

I saw how people were able, in 2005, to occupy those estates. But it wasn’t a gift granted from above; it was a confrontation that the campesinos won with blood, sweat, and tears. It was their victory. In the final battle you could see how, on one side, there were the landless people, while on the other side were the “pantaneros,” the landowners’ goons. The landowners were also supported by the Yaracuy state police, which at the time was controlled by the opposition.

It was a harsh battle and some comrades were injured, but in the end, the pueblo won!

A few years later, at age 16, I joined Misión Robinson: I went to rural communities to teach campesinos who hadn’t had a chance to go to school to read and write. I was born in the township of Urachiche itself, not in the campo, so this experience allowed me to understand the everyday realities of rural life.

After high school, I studied Social Work at the Bolivarian University of Venezuela, which had recently begun offering municipalized education [non-campus-based schooling]. It was there that I met my life partner, who is himself deeply committed to the campesino struggle. My final project at the university involved working with people who were making a communal council. That’s when I fell in love with grassroots work, and learned that building people’s power from below was my true calling.

A few years later, when Chávez called on the people to build communes, a group of die-hard Chavista comrades began the long march that ultimately led to the founding of the Alí Primera Commune. The roads were in terrible shape and we had to do grueling hikes through the mountains to get people organized, but none of that stopped us. Up in the heights of Urachiche, rain or shine, we helped build a beautiful commune!

The campesinos gave us everything they had—including knowledge, organization, and hospitality. When we arrived in remote hamlets, people would offer coffee and arepas, even when they had practically nothing to feed themselves.

Those experiences and the difficult yet dignified ways of campesino life made me even more committed to building a different kind of society, a socialist one.

That long process shaped who I am and reinforced my bond with the people. I believe it was because of my deep-rooted commitment to community-building that the people of Urachiche elected me twice as a city council member. Now, they’ve asked me to take on the challenge of the mayor’s office, and I’ve accepted it. Through our work with Urachiche’s 48 communal councils and its three communes, I’ve come to understand people’s needs, so I think I’ll be equal to the challenge.

I aim to build a municipal government that governs by obeying, a government that creates the conditions for the communes to thrive both economically and organizationally. My vision is for Urachiche to become a pioneer in building a communal city [aggregation of several communes], where the three communes in the municipality—Camunare Rojo, Alí Primera, and Hugo Chávez—come together through a popular parliament, placing people’s power at the heart of municipal decision-making processes.

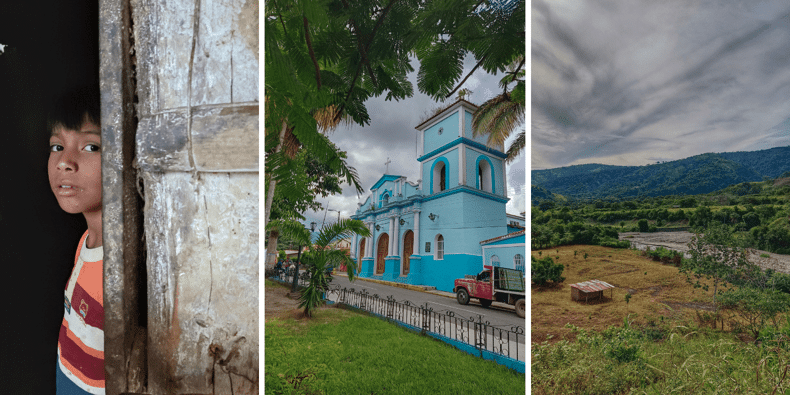

Urachiche and its people. (Voces Urgentes)

CPM: Leadership roles in communes are most often assumed by women, but local governments tend to be dominated by men. As a candidate from the grassroots and as a woman, how do you plan to confront patriarchy in institutional politics?

LCP: In recent days, as I’ve been going door-to-door in Urachiche. One phrase that I keep hearing is: We’re glad it’s a woman running for mayor. Urachiche has matriarchal roots: the Indigenous peoples who inhabited this territory before colonization were matriarchal, and that legacy still persists in our culture.

Even so, colonization implanted patriarchy, and its structures persist to this day. That’s why we must build real mechanisms to combat gender-based violence and dismantle the male-dominated culture that continues to shape institutional politics, where feminism too often remains a slogan rather than a real practice.

I want to show that women are fully capable of governing and, more than that, I aim to demonstrate that the distinct sensibilities women bring to leadership can be harnessed to address the social challenges facing our communities. Ultimately, my presence in the institutions should help to empower those who have been most marginalized by both capitalism and patriarchy.

I will lead by example, in the spirit of the Indigenous warrior women who once lived in these lands. Here we are, the heirs of Ana Soto [1618—1668], the cacica who led the resistance against colonial domination. Centuries of imposed patriarchy have shaped our culture, but I am determined to show that women can govern, transform reality, and help build a communal society where women live with dignity, free from both capitalist exploitation and patriarchal oppression.

CPM: The U.S. blockade took a heavy toll on production in the Urachiche mountains, both because agricultural inputs became prohibitively expensive and because fuel prices and poor road conditions made it difficult to get crops to market. If elected mayor, how do you plan to address these and other problems induced by the blockade?

LCP: We know that, for rural communes to thrive, they must have not only good roads and access to agricultural inputs, but they must also control means of production. Only through a communal economy can we generate new social relations and fully overcome the impact of the US’ unilateral coercive measures. As long as there is private ownership of the means of production, socialism will remain out of reach… with or without the blockade!

We aim to build socialism, and the commune is the path to get there. However, socialism is not built from the grassroots alone. Working people may be the engine of the revolution, but coordinating with institutions is needed to ensure that communes can begin to hegemonize society both politically and economically.

From the mayor’s office, we’ll work hard to provide communes with the land and the means of production that they need to thrive. Urachiche’s land is among the most fertile in Venezuela, yet many needs remain unmet.

Our territory is ideal for growing coffee, avocado, corn, pineapple, legumes, and vegetables. However, the knowledge of our campesinos remains underutilized. I believe if the mayor’s office is fully committed to people’s power, we’ll be able to not only resist the blockade, but also advance toward building a socialist communal economy.

The people of San Simón. (Voces Urgentes)

CPM: Communes generally strive for self-government, whereas town governments are not always supportive of the communes. How do you plan to coordinate the two sides? Do you see a risk of bureaucratization?

LCP: Bureaucratization is always a risk when one enters institutional spaces. However, I think I’ve managed to avoid it during my eight years as a council member. That’s because I’ve kept my priorities clear: people come first.

For that reason, I’m always in the streets, in the assemblies, in the debates—helping to bring to fruition the majority’s dreams, and working alongside the majority. That’s how I’ve been able to remain true to what is most essential.

Perhaps that’s also why, at a time when the “communal state” discourse has become central among the Bolivarian leadership, the people chose me to run for mayor.

Now we face a new challenge: how to work within the framework of the liberal state—the very structure Chávez urged us to move beyond—to advance what is communal, while leaving behind everything that is bureaucratic and goes against the interests of the pueblo.

The existing municipal structure must be reoriented toward strengthening communal self-management. For that to happen, the mayor’s office will have to leave its cubicles and move into the streets and into the grassroots assemblies. Planning and governance should be done with direct popular participation.

We aim to build a Communal Parliament that will overcome outdated institutional forms. This must be done in an alliance between the Hugo Chávez, Alí Primera, and Comunare Rojo communes. The communes are the only institutions that can liberate the future of the pueblo.

We also wish to link up with other communes across the country. Most importantly, we want to carry out Chávez’s order: power and resources should be transferred to the people. For that to happen, we need to help consolidate self-government in the territories.

In short, I, Lisbed Carolina Parada, will do everything in my power to remain true to what we’ve been building over the past 15 years, when we began making communal councils and communes in Urachiche. I will also work hard so that the communal project makes qualitative progress in Urachiche.

A communal assembly at the Alí Primera Commune, in the mountains of Urachiche. (Alí Primera Commune)

CPM: In the Alí Primera Commune, the communards say they “have Chávez in their hearts” and they draw inspiration from Alí Primera’s revolutionary music. How will you translate the legacy of Alí and Chávez into concrete policies for the Urachichet township?

LCP: The full slogan we use is: “Chávez in our hearts and socialism on the horizon.” That phrase encapsulates what we live and breathe in our communes. Chávez emerged at a time when the global left was in retreat. Yet he revived the popular cause and its historic ideals. That’s why he is in our hearts.

Meanwhile, Alí Primera’s music calls on us to stand with the campesino and with all those capitalism destroys. His songs also remind us that the guerrilla struggle that once took place in these mountains is a vital part of our history.

But our references don’t stop with Chávez and Alí. We also honor Dimas Petit, a local hero, guerrilla, and PRD [revolutionary party] founder; Fabricio Ojeda, the guerrillero and journalist who passed through our mountains; and our teacher Felipe Rojas, who picked up a rifle at age 13 to fight for justice, never wavering until his last breath.

Their legacy inspires our commitment: we are determined to turn their utopias into tangible realities. This means showing up at every assembly and working to improve rural roads to ensure that campesinos can bring their crops to market.

We must also implement financial policies that empower communal banks to support strategic crops such as coffee, avocado, corn, sugarcane, pineapple, and vegetables. By working closely with campesino grassroots organizations, we will not only meet local demand but also expand production beyond our territory.

All this is already reflected in our Municipal Government Plan, which was developed from the ground up through participatory assemblies. Every communal council and each of the three communes here helped shape this concrete agenda for action.

The Plan encompasses a broad range of initiatives, from gradually transferring public services to the communes and generating dignified employment for the youth, to creating communal enterprises and supporting family-run production units.

We want to demonstrate that Chávez didn’t struggle in vain. Another world is possible! Together we can lay the foundations for a communal society and a new civilization!