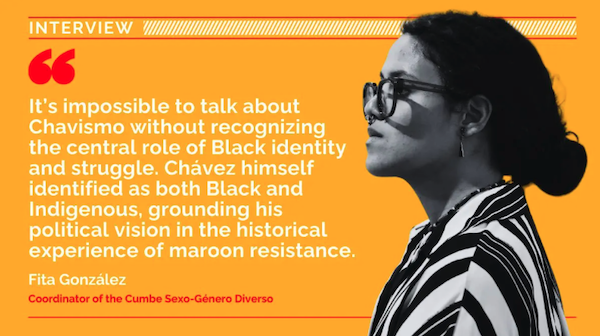

Fita González is a militant of the Cumbe Nacional Afrovenezolano [National Afro-Venezuelan Cumbe] and coordinator of the Cumbe Sexo-Género Diverso [Sex-Gender Diverse Cumbe]. An educator and photographer, González also studies Afro-Venezuelan singing and percussion. Their work weaves together activism, culture, and political education from a distinctly Black and queer perspective.

In this conversation, González reflects on the living legacy of Afro-Venezuelan resistance, especially the cumbe [maroon community] as a space of self-organization. They also consider the intersections between Black liberation, communal power, and the Bolivarian Process—while looking at the struggles that lie ahead, which include constitutional recognition and intersectional organizing.

Cira Pascual Marquina: How do you assess the Bolivarian Process today, particularly from the perspective of Black struggles in a country where more than half the population is of African descent?

Fita González: According to the most recently published census [2011], 54% of Venezuela’s population is Afro-descendant [amply understood]. We have long been at the forefront of revolutionary struggle—not only in the Bolivarian Process, which has advanced key goals for Afro-descendant communities, but since the earliest battles against colonial rule.

It’s impossible to talk about Chavismo without recognizing the central role of Black identity and struggle. Chávez himself identified as both Black and Indigenous, grounding his political vision in the historical experience of maroon resistance. Over the past 25 years, Afro-Venezuelans have been present at every decisive moment of the Bolivarian Process: from drafting the Constitution to restoring Chávez to power [2002], participating in electoral battles, organizing at the grassroots level, and answering every call to defend the revolution.

CPM: Within the Bolivarian Process, significant legal advances have been made for Afro-descendants. However, structural racism persists. Can you tell us about some of the successes and also the pending tasks, especially with a view to the upcoming constitutional reform?

FG: One of the most important victories for the Black movement was the approval of the “Law Against Racial Discrimination” [2011]. This law paved the way for the legal and political recognition of Afro-descendant identity, and it was the result of ma of work by the Network of Afro-Venezuelan Organizations [ROA].

But of course, laws don’t change society on their own. Any legal victory must go hand in hand with grassroots education, political formation, and cultural work. When we are talking about uprooting structural racism, the struggle must be permanent.

The formation of the ROA would eventually give rise to what we now call the Black Academy [Academia Negra]. Although the Academy has recently gained visibility through its role in the Committee for Historical Truth, its roots run much deeper.

The Committee for Historical Truth was installed in 2022 by President Nicolás Maduro. Its objective is to examine the impact of colonialism and eventually demand reparations. The Black Academy plays a crucial role in this project of collective justice.

Our Academy brings together Black scholars—anthropologists, sociologists, and political thinkers, including Casimira Monasterios, who is the general coordinator of the Cumbe Nacional; Jesús “Chucho” García, the current president of ROA; Lilia Ana Márquez Ugueto; Beatriz Aiffil; and many other maroon scholars who have turned their research into a political instrument. Their work gives greater depth and historical context to our struggle and helps strengthen the fight against structural racism.

Thanks to these ongoing efforts, we are now actively promoting the constitutional recognition of Afro-descendant people as a distinct political subject with collective rights—similar to the status already granted to Indigenous peoples. We represent a foundational part of the Bolivarian Revolution with our very own history, so our existence should be formally acknowledged in the Constitution.

We are confident that the upcoming constitutional reform will finally deliver justice on that front.

Maroon assembly in Vigirima, Carabobo state, 2023. (Photo: Fita González)

CPM: Since the early years of the Fourth Republic [1958—1999], Venezuela has often been framed as a “café con leche” nation—a metaphor that suggests racial harmony through mixing. Yet many people believe that this discourse hides deep structural inequalities and erases the historical struggles and revolutionary agency of Black people. What is your view of that subject?

FG: The rejection of that kind of myth is what led many of us to join the Afro movement. We reject the idea of “improving the race”—a phrase that’s still common in Venezuela—and we reject the ideology of mestizaje [mixing] when it is used to erase our identities.

We exist as who we are. We do not need to be diluted or transformed into something else to be accepted. Our struggle begins with that recognition.

CPM: The Red de Organizaciones Afrovenezolanas promotes Black organizing and brings together diverse Afro-descendant movements. Among them is the Cumbe Nacional, founded in 2022. Can you explain the cumbe, both as a historical form of resistance to enslavement and as a contemporary expression of collective identity?

FG: The Cumbe Nacional is a strategic space for political education, organization, and collective deliberation, but its roots reach back to the era of slavery. During colonial times, enslaved Africans who escaped the plantations—cimarrones and cimarronas—fled to the mountains and established cumbes: autonomous communities where they rebuilt social, political, and economic life on their own terms, drawing from ancestral knowledge and values.

These territories of freedom were powerful expressions of self-governance, directly challenging the colonial order. While the term cumbe refers to Venezuelan social formations of this kind, similar liberated territories existed across the Caribbean and the Americas, although they were known by other names, such as quilombos in Brazil and palenques in Colombia.

Many Afro towns, such as Curiepe [Miranda state], originated as cumbes. That legacy is alive in the ways people live, organize, and think politically. So, when we speak of cumbes today, we are naming both a historical form of maroon resistance and a present-day strategy for organizing Black territories. The cumbe is the political, cultural, economic, and even spiritual foundation for our movement.

CPM: Historically, cumbes tended to be deeply democratic spaces, based on collective ownership and governance. Would you say that holds true for the Cumbe Nacional as well?

FG: Absolutely. Many of the Africans who were kidnapped and brought to Venezuela came from similar ethnic groups and clustered [roughly according to origin] through what we now know as Venezuela. For example, in the central and coastal areas of Carabobo, parts of Yaracuy and Lara, there are strong cultural and political affinities linked to communities with origins in modern-day Congo. In other areas, like Guárico, the Yoruba presence is more prominent.

These shared roots led to the creation of highly cohesive cumbes, and those territories still display a strong sense of kinship and collective identity. They identify as cumbes today, regardless of whether they were cumbes in the past. They also often continue to be spaces of self-governance, solidarity, and deep-rooted democracy.

CPM: I understand that there are now 36 self-identified cumbes that can be found in 13 of Venezuela’s states, and that they are now organized by the Cumbe Nacional. Can you tell us how they came to self-identify as cumbes, and how they are now organized?

FG: The process began with the creation of the Consejo Nacional para el Desarrollo de las Comunidades Afrodescendientes [National Council for the Development of Afro-Descendant Communities], which was one of the last institutions signed into law by President Chávez in 2012. It was established alongside the Instituto Nacional contra la Discriminación Racial [National Institute against Racial Discrimination]. These two institutions had the task of identifying Afro-descendant populations and territories.

Identifying self-recognized Afro territories has been essential to advancing the political education efforts led by the Black Academy and the broader Afro movement. Since around 2020, we’ve been working intensively on a census, but the challenge is immense. Racial recognition is not merely quantitative—it’s deeply ideological and political. Race itself is a construct embedded in dominant ideology, and dismantling that is no easy task. Even in recent censuses, many people continue to identify using colonial caste terms like mulato, zambo, moreno, or simply negro. Only about 10% explicitly identify as Afro-descendant.

Still, the existing data has allowed us to develop a tighter relation between the Black Academy and Afro territories. We’ve established permanent lines of communication, political education, and coordination with the 36 self-identified cumbe territories.

In this process, one of the key ideological advances was the recognition of intersectionality as a fundamental interpretive principle and as a political tool.

CPM: How does intersectionality function as an interpretive principle in practice, and how did it contribute to the recent creation of the Cumbe Sexo-Género Diverso?

FG: The concept of intersectionality didn’t originate in Venezuela, but it has always been present in our struggles. In other words, understanding that oppression is not unidimensional, but that it often combines race, class, gender, etc., is nothing new for us.

For example, Argelia Laya [1926-1997] theorized about overlapping forms of oppression long before the term “intersectionality” was widely used. Today, we understand that to confront racism in our society, we also have to address other forms of oppression, including patriarchy, transphobia, and homophobia.

This understanding led us to create a new space: the Cumbe Sexo-Género Diverso. This Cumbe is only a few months old, and it emerged out of a deep need for a place where Black people with diverse gender and sexual identities could come together, see one another, and begin a process of political education and organization.

For now, the most visible expression of this Cumbe is on social media. We are only organized in Caracas, but we’re very aware that this community exists across the country—we need to build substantive links. The idea is to begin with identity, getting to know ourselves and our histories, and then deepen our political education. As we do this, we are drawing from the theoretical and pedagogical work of the Black Academy, especially its contributions to Afro-epistemology and maroon thought.

CPM: Let’s return to the historical cumbes. You said that today, most spaces that self-identify as cumbes have a territorial basis. What is their relationship with the communes, which are also territorial organizations and considered the cells of socialism in Venezuela?

FG: Historical cumbes were communal, so there is a great deal of resonance between Chávez’s commune and the cumbes. In some cumbe territories, however, there is a rich debate about how to name themselves: is the cumbe above or below the commune? However, in most places, the debate is not framed in hierarchical terms. Instead, people see how both concepts can coexist harmoniously.

In fact, the communal project has helped many to reconnect with their historical and cultural identities. It’s one thing to recognize yourself as Afro-descendant on an individual level, but it’s something entirely different to recognize an entire community and its territory—a commune-cumbe or cumbe-commune—as Afro-descendant. That shift in perspective has opened new paths for self-governance and the recovery of historical memory.

The commune is a project for the emancipation of the pueblo. But it’s not just about economic self-management, it’s also about political and cultural liberation, and about territorial recognition. The communal project has been important in helping our broader movement take an important step: from individual self-recognition as Afro-descendants, to building collective recognition of Afro-descendant communities with deep territorial roots that formally express themselves as communes.

In some places, people are still working through these ideas, but what’s exciting is that every Black territory is finding its own way. The debates are rich ones, and they are necessary. People are asking: How does our way of living, of organizing economically and culturally, fit within the communal system? Can we merge the traditions inherited from our ancestors—those who built the original cumbes—with the communal model in place today? In the end, these aren’t contradictions; they’re political processes of naming and reclaiming self-governance.

None of this would have been possible without the Bolivarian Revolution!

San Benito birthday celebration, 2024. (Photo: Fita González)

CPM: Venezuela is rich in expressions of Black culture—including music, spirituality, and celebration. But what the academy has often identified as merely “folklore” is deeply political and even subversive. Could you talk about that dimension of Black society in Venezuela?

FG: The practice of the Cumbe Nacional, and in general the Black movement, can never be separated from our spiritual beliefs. Spirituality is one of the foundational pillars of our political practice. In many Afro territories—especially in the “Pueblos Santos” in Sur del Lago [Zulia and Mérida states]—the governance of the community is tied to the figure of the “capitán” of the San Benito brotherhood. San Benito is a Black syncretic figure that inhabits a Catholic church, but is also linked to Ajé, an African deity. This is most evident when the saint is taken on a procession and people chant: Ajé, Ajé San Benito, Ajé.

The capitanes aren’t chosen randomly; the community elects them democratically in recognition of their spiritual connection to the saint, to the people, and to the instruments they play. They are chimbangaleros [drummers] or cantadores [singers], and they are respected cultural figures and moral authorities. But they are also political leaders. In their towns, they often have the final word. They provide guidance and direction.

We see the same thing with the Cofradías de San Juan along the central coast, including those in Caracas. While there are fewer formal cofradías [brotherhoods] in the capital, musical collectives play a similar role. The leaders of the cofradías are often political leaders too. They are our elders, our teachers, and they carry the wisdom that guides us.

These spiritual practices are central to Black communities. City contexts make this more difficult, of course. However, even in urban spaces, it is evident how cultural leadership can evolve into political leadership. In fact, in Grupo Herencia, which is the force behind the Universidad Venezolana del Tambor, teachers speak directly about this: about how Afro-descendant knowledge circulates in the city and becomes a political compass.

Each community has its own style, its own way of decorating, playing, and celebrating. And that’s not just aesthetic. It’s a way of knowing who we are and where we come from. Even the colors of the saints vary: San Juan may be clad in red and white in one place, and in green and orange in another. Those variations are not superficial; they are rooted in collective memory, culture, and historical experience.

So when we talk about culture and spirituality, we’re also talking about organization, leadership, and liberation. This is how we transcend colonial frameworks and build our own way of life.