Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

As the United States and its allies put pressure on Venezuela, a poem by the Salvadoran radical Roque Dalton (1935-1975) clarifies the structure of politics in Latin America. Dalton came from one of Latin America’s smallest countries, El Salvador, which he used to call the little finger (pulgarcito). A deeply compassionate poet, Dalton was also a militant of the People’s Revolutionary Army, whose internal struggles claimed his short life. El Salvador, like so many other Latin American states, struggles to carve out its sovereignty from the tentacles of U.S. power. That hideous Monroe Doctrine (1823) seemed to give the U.S. the presumption that it has power over the entire hemisphere; ‘our backyard’ being the colloquial phrase. People like Dalton fought to end that assumption. They wanted their countries to be governed by and for their own people–an elementary part of the idea of democracy. It has been a hard struggle.

Dalton wrote a powerful poem–OAS–named for the Organisation of American States (founded in 1948). It is a poem that acidly catalogues how democracy is a farce in Latin America. It is from the poem that we get the title of our newsletter this week.

The president of my country

for the time being is Colonel Fidel Sanchez Hernandez

but General Somoza, president of Nicaragua

is also the president of my country.

And General Stroessner, president of Paraguay,

is also kind of the president of my country, though not as

much as the president of Honduras,

General Lopez Arellano, but more so than the president of Haiti,

Monsieur Duvalier.

And the president of the United States is more the president of my country

Than is the president of my country,

The one whose name, as I said,

is Colonel Fidel Sanchez Hernandez, for the time being.

Is the President of Venezuela the President of Venezuela or is the President of the United States the President of Venezuela? There is absurdity here. Collapsed oil prices, reliance upon oil revenues, an economic war by the United States and complications in raising finances has led to hyperinflation and to an economic crisis in Venezuela. To deny that is to deny reality. But there is a vast difference between an economic crisis and a humanitarian crisis.

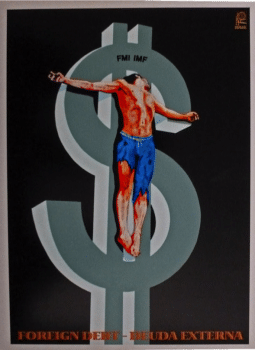

Most of the countries on the planet are facing an economic crisis, with public finances in serious trouble and with enormous debt problems plaguing governments in all the continents. This year’s meeting of the World Economic Forum at Davos (Switzerland) focused attention on the global debt crisis–from the near-trillion-dollar deficit of the United States to the debt burdens of Italy. The IMF’s David Lipton warned that if interest rates were to rise, the problem would escalate. ‘There are pockets of debt held by companies and countries that really don’t have much servicing capacity, and I think that’s going to be a problem’.

Hyper-inflation is a serious problem, but punitive economic sanctions, seizure of billions of dollars of overseas assets and threats of war are not going to save the undermined Bolivar, Venezuela’s currency.

Eradication of hunger has to be the basic policy of any government. According to the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organisation, 11.7% of the Venezuelan people are hungry. Hunger rates in other parts of the world are much higher–31.4% in Eastern Africa. But the world’s attention has not been focused on this severe crisis, one that has partly generated the massive migration across the Mediterranean Sea. The picture above is from the European Parliament in Strasbourg, where–in 2015–activists laid out the 17,306 names of people who have died attempting that crossing (the number is now close to 40,000 drowned). Members of the European parliament had to walk to their session over these names. They are harsh in their attitude to start a war against Venezuela, but cavalier about the serious crises in Africa and Asia that keep the flow of migrants steady.

The government of Venezuela has two programmes to tackle the problem of hunger:

- Comité Local de Abastecimiento y Producción (CLAP). The Local Committees for Supply and Production are made up of local neighbourhood groups who grow food and who receive food from agricultural producers. They distribute this food to about six million families at very low cost. Currently, the CLAP boxes are being sent to households every 15 days.

- Plan de Atención a la Vulnerabilidad Nutricional. The most vulnerable of Venezuelans–620,000 of them–receive assistance. The National Institute of Nutrition has been coordinating the delivery of food to a majority of the country’s municipalities. These are useful, but insufficient. More needs to be done. That is clear. Through CLAP, the Venezuelan government distributes about 50,000 tonnes of food per month. The ‘humanitarian aid’ that the U.S. has promised amounts to $20 million–which would purchase a measly 60 tonnes of food.

1st U.S. PSYWAR (Psychological War) battalion hands out anti-communist posters in Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic), 1965.

On the issue of ‘humanitarian aid’ to Venezuela, the international media has become the stenographers of the U.S. State Department and the CIA. It focuses on the false claims made by the U.S. government that it wants to deliver aid, which the Venezuelans refuse. The media does not look at the facts, even at this fact–that $20 million is a humiliating gesture, an amount intended to be used to establish the heartlessness of the government in Venezuela and therefore seek to overthrow it by any means necessary. This is what the U.S. government did in the Dominican Republic in 1965, sending in humanitarian aid accompanied by U.S. marines.

The U.S. has used military aircrafts to bring in this modest aid, driven it to a warehouse and then said that the Venezuelans are not prepared to open an unused bridge for it. The entire process is political theatre. U.S. Senator Marco Rubio went to that bridge–which has never been opened–to say in a threatening way that the aid ‘is going to get through’ to Venezuela one way or another. These are words that threaten the sovereignty of Venezuela and build up the energy for a military attack. There is nothing humanitarian here.

If you don’t let us breathe, we won’t let you breathe. Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2019. (Photograph: Hector Retamal.)

The term ‘humanitarian’ has been shredded of its meaning. It has now come to mean a pretext for the destruction of countries. ‘Humanitarian intervention’ was the term used to destroy Libya; ‘humanitarian aid’ is being used to beat the drum for a war against Venezuela. Meanwhile, we forget the humanitarian solidarity offered by the Venezuelan government to the poorer nations and to poorer populations. Why is Haiti on fire now? It had received reduced price oil from Venezuela by the PetroCaribe scheme (set up in 2005). A decade ago, Venezuela offered the Caribbean islands oil on very favourable terms so that they would not be the quarry of monopoly oil firms and the IMF. The economic war against Venezuela has meant a decline in PetroCaribe. Now the IMF has returned to demand that oil subsidies end, and monopoly oil firms have returned to demand cash payments before delivery. Haiti’s government was forced to vote against Venezuela in the OAS. That is why the country is aflame (for more on this, please read my report). If you don’t let us breathe, say the Haitian people, we won’t let you breathe.

In 2005, the same year as Venezuela set up the PetroCaribe scheme, it created the PetroBronx scheme in New York City (USA). Terrible poverty in the South Bronx galvanised community groups such as Rebel Diaz Arts Collective, Green Youth Cooperative, Bronx Arts and Dance, and Mothers on the Move.

They worked with CITGO, the Venezuelan government’s U.S. oil subsidiary to develop a cooperative mechanism to get heating oil to the people. Ana Maldonado, a sociologist who is now with the Frente Francisco de Miranda (Venezuela), was one of the participants in the PetroBronx scheme. She and her friends created the North Star to be a community organisation that helped deliver the resources to the very poorest people in the United States. ‘People had to wear their coats inside their homes during the winter’, she told me. That was intolerable. That is why Venezuela provided the poor in the United States with subsidised heating oil.

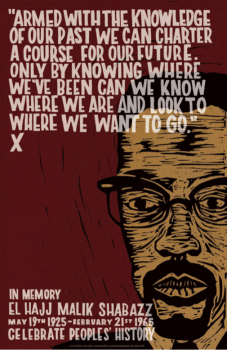

Josh MacPhee, Malcolm X, (Photo Credit: Just Seeds).

The South Bronx and Harlem, the privations produced by racism–all this is familiar territory in Latin America. In 1960, Fidel Castro came to New York to attend the United Nations General Assembly. He was refused a hotel in the city. Malcolm X, a leader of the African American community, came to his aid, bringing the Cuban delegation to Harlem’s Hotel Theresa, whose owner–Love B. Woods–warmly welcomed Fidel and his comrades. Four years later, at a meeting in Harlem, Malcolm X said in connection with his meeting with Fidel, ‘Don’t let somebody else tell us who our enemies should be and who our friends should be’.

Warmly,

Vijay.