Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) consists of fifteen members, five of them permanent members with veto powers (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States) and ten members who are elected for a two-year term. The presidency of the Council rotates monthly. This month–in May–the council’s presidency is held by Indonesia, whose permanent representative is Dian Triansyah Djani–a career diplomat. The President of Indonesia is Joko Widodo, known as Jokowi. Khamid Istakhori, General Secretary of Federasi SERBUK–a large trade union federation in Indonesia–has written an open letter to the President. He asks Jokowi to use Indonesia’s presidency of the UNSC to denounce violations of international law against Venezuela. Khamid sent us this letter, which forms the centre of this week’s newsletter. Please read his words below.

Sukarno at the Asian-African Conference, Bandung, Indonesia, 1955

Open letter to President Joko Widodo

You have not gathered together in a world of peace and unity and cooperation. Great chasms yawn between nations and groups of nations. Our unhappy world is torn and tortured, and the peoples of all countries walk in fear lest, through no fault of theirs, the dogs of war are unchained once again.

These were the words of Indonesian President Sukarno as he opened the first Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung in 1955, which laid the groundwork for the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), the key political institution that for decades called for the emancipation of the Global South.

As the drums of war beat ever louder in Caracas and Washington, we call on Indonesian President Joko Widodo–President of the United Nations Security Council for the month of May 2019–to use that position to make a stand for a world of peace, unity and cooperation, and denounce the violations of international law that have been committed by the United States in its campaign to destabilise Venezuela.

On numerous occasions this year the Venezuelan opposition have attempted a coup d’etat against the democratically-elected Government of President Nicolas Maduro, each with U.S. assistance. For example, on 28 January 2019 the U.S. issued an Executive Order recognizing opposition leader Juan Guaidó as interim president. Simultaneously it has attempted to use food and medical aid to alleviate the suffering imposed by its own sanctions regime, designed to strangle the Venezuelan economy. This regime, designed to strangle the Venezuelan economy, costs Venezuela U.S. $30 million per day. For comparison, a recent shipment of aid that the U.S. attempted to deliver carried only U.S. $20 million in supplies; less than a single day’s worth of caused by the sanctions.

U.S. sanctions–which have frozen US$30 billion of Venezuela’s assets in the U.S. and caused the country losses of US$23 billion from August 2017 to December 2018–have hit the Venezuelan people most directly. In a report to the UN Human Rights Council Alfred de Zayas noted that the sanctions were a conscious act that ought to be considered crimes against humanity.

In a recent paper Weisbrot and Sachs argued they have ‘reduced the public’s caloric intake, increased disease and mortality (for both adults and infants), and displaced millions of Venezuelans who fled the country as a result of the worsening economic depression and hyperinflation’. They estimate that the sanctions–illegal under both U.S. law and the statutes of the Organisation of American States–have caused an estimated 40,000 civilian deaths from 2017-18 and reach the threshold of the Geneva Convention’s definition of ‘collective punishment’.

Most recently, U.S. police have forcibly entered the Venezuelan Embassy in Washington–a clear violation of article 22 of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations–arresting its occupants and handing it over to the Venezuelan opposition.

While the U.S. has been vocal in its opposition to human rights violations, its actions have been motivated by a desire to crush Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution and the impact it has had on limiting U.S. access to the region’s resources, particularly Venezuelan oil. In addition to improving living conditions for millions of poor and dispossessed, the Bolivarian Revolution ignited a new direction for solidarity in the Global South.

Venezuela joined the NAM in September 1989 just months after the Caracazo, a wave of protests in response to neoliberal economic reforms. The Caracazo was triggered by the rising price of oil as newly-elected centrist President Carlos Andres Perez removed subsidies.

The Caracazo was a key turning point for Venezuela. From a hospital bed future President Hugo Chávez watched the violence unfold as hundreds (maybe thousands) were killed by the state security apparatus in what Chávez later called a ‘genocide.’

After taking power in a 1998 election, Chávez’s Government used oil rents to benefit the people of Venezuela (and the other countries which later joined the Bolivarian project), slashing poverty, raising wages and improving access to food, healthcare and education (see here for a brief account of its achievements). In 2002 Chávez and his loyal military supporters successfully defended the Bolivarian Revolution against a U.S. -orchestrated coup.

Chávez’s successor Nicolás Maduro has sought to continue this legacy. He has won numerous democratic elections despite the fact that his leadership has been severely tested by the collapse of oil prices, which account for roughly 95% of Venezuelan exports. The U.S. and Venezuelan opposition have seized on this as an opportunity to undermine the ideological project of the Bolivarian Revolution and access Venezuela’s oil wealth.

The actions perpetrated against Venezuela raise troubling memories for many Indonesians. Documents declassified in 2017 demonstrate that rather than just ‘standing by’ while an estimated half a million civilians were massacred by General Suharto and his troops in 1965, the U.S. was actively engaged in spreading the narrative that justified the violence.

Despite ending formal military rule in 1998, the legacy of military control still hangs heavy over Indonesia. For years it remained a recipient of U.S. military aid, and an active participant in U.S. military training exercises. Former President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono even spent time training at the Fort Benning ‘School of the Americas’, the infamous training ground where Latin America’s coup-plotters sharpened their skills for decades.

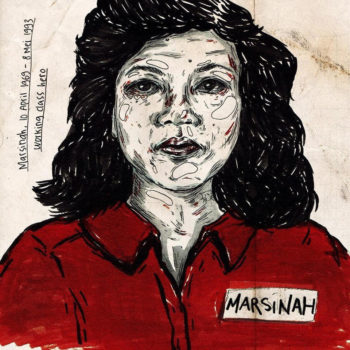

Marsinah was an Indonesian factory organiser, killed 26 years ago this month by the Suharto dictatorship. ‘They play between the numbers’, wrote Ratna Sarumpaet in her play Marsinah Menggugat. ‘They never consider whether a number of numbers can humanise a worker’ [Mereka bermain diantara angka-angka. Mereka tidak pernah mempertimbangkan apakahsejumlah angka mampu memanusiakan seorang buruh]. Art by Ivana Kurniawati.

Jokowi has so far been reluctant to take a firm stand on Venezuela, beyond expressing concern and encouraging political dialogue between parties. However, while Indonesia claims to respect the principle of non-interference and not interfere in the internal affairs (restricting comment to humanitarian assistance for the displaced), it has failed to speak out against the consistent interference and violations of international law we are seeing in Venezuela.

As when Sukarno spoke in Bandung, the dogs of war are again unchained, and they have their teeth firmly trained on Venezuela. We stand in solidarity with the working classes of Venezuela, and support the steps taken by President Maduro to overcome the crisis.

Accordingly, we call on Jokowi to use the final week of his presidency of the Security Council to live up to the legacy of Sukarno, denounce the violations of international law committed by the U.S., and begin rebuilding the solidarity of the Global South.

—Khamid Istakhori, General Secretary of Federasi SERBUK.

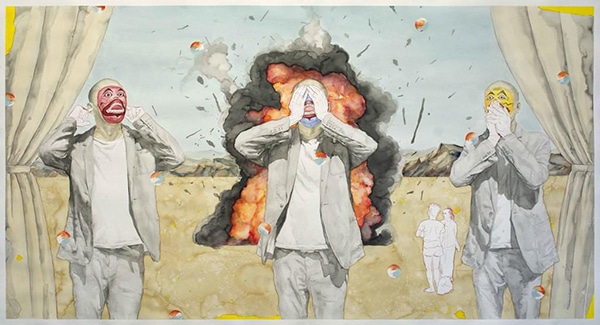

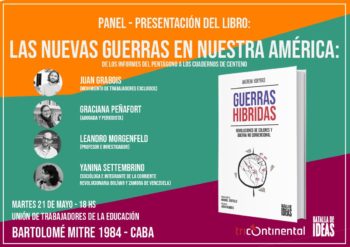

Coming up in June, our Dossier no. 17 on the attack on Venezuela and the concept of the hybrid war. This dossier is produced jointly by our offices in São Paulo (Brazil) and Buenos Aires (Argentina). It is a thorough assessment of the nature of the war on Venezuela, one of the four wars that John Bolton–the U.S. National Security Advisor–is eager to prosecute (for more on this, see my column). As our offices prepared the dossier, our team in Buenos Aires held a seminar to discuss the Spanish translation of Andrew Korybko’s book on hybrid war.

After seven gruelling weeks, the election results for India’s 17th Lok Sabha (Parliament) are now out. Nine hundred million voters were registered to vote in 542 constituencies. The far-right BJP won a majority of seats and will once more form the government. It is a sobering fact that the far-right continues to make gains around the world. This is not a story about India itself, not a story that can be explained by an empirical dive into Indian realities alone. It is a global story, from Australia to Brazil. It requires a close assessment of the structural forces of globalisation and the social fragmentation that these have produced.

Last week, I was in Dublin (Ireland) where I spoke at a Workers’ Party event for the elections to the European Parliament. At this event, I talked about how the far-right does not address the grave problems in our world but relies upon the strains of society to form its electoral bloc:

Dublin, Ireland, 7 May 2019.

We need to pay attention to these structural realities as much as we need to understand the sociological change in our societies as a result of the processes of globalization.

We will be doing a dossier on the Indian election results later this year, as well as continuing with our investigations on the idea of ‘democracy’ in our times.

Warmly, Vijay

PS: to read our previous newsletters and the other materials, please visit our website. There you will find our dossier on Resource Sovereignty. Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research coordinator Celina della Croce’s article this week draws out the themes from that dossier.