Despite its reputation as the wealthiest generation, baby boomers (generally considered to be those born between 1946 and 1964) are facing a retirement nightmare. A 2016 St. Louis Federal Reserve study of the retirement readiness of U.S. families came to the same conclusion but put it more gently: “It could be worrisome that, for many American households, the total balances of their retirement accounts may not be sufficient to ensure a solid life in retirement.”

The investment industry, always ready to deflect blame, argues that the problem is the result of the fact that Americans just don’t save enough. But even Barron’s, a sister publication of the Wall Street Journal that specializes in financial news, understands what is really happening. As a recent article in the magazine points out:

Too few Americans are saving for retirement. Those who do save are putting away too little. It is only a matter of time before this sparks an economic and political crisis. . . .

But America’s retirement crisis wasn’t created because of character flaws or personal irresponsibility. Nor can it realistically be fixed by technocratic fixes.

The ugly, unspoken truth is that many people are just not earning enough money. They barely have enough to cover their daily expenses; they don’t have enough left over to be able to save.

The promised golden years are out of reach for most boomers.

Baby boomers are moving rapidly towards retirement. Those born in 1946 are now 73, those born in 1964 are now 55. Despite being celebrated for their good economic fortune, especially in contrast to millennials, most boomers face a future that doesn’t include retirement with dignity or, in the words of the St. Louis Fed, a solid life.

Although labeled the wealthiest generation, a Stanford Center on Longevity examination of retirement preparedness found that “baby boomers are in a financially weaker position than earlier generations of retirees, in terms of home equity accumulation, financial wealth, and total wealth.”

The Stanford Center study divided the boomer generation into two groups, the early boomers (born 1948-1953) and mid-boomers (1954-1959), and compared them to early (before 1942) and later born (1942-47) members of the previous “silent generation.” The following are some of its key findings:

- Holding age fixed, mid-boomers age around 55-60 years old had saved less than previous generations at the same age.

- Holding age fixed, a 50-year old mid-boomer had saved less in any retirement plans, including workplace plans and Individual Retirement Account plans, than a 50-year old from prior generations.

- Holding age fixed, boomers age 55-60 had a higher debt burden than prior generations at the same age, evidenced in a higher debt-to-net worth ratio, a lower liquid-asset to all asset ratio, and a higher loan-to-value ratio.

But boomer problems are not just comparative. For example, the Stanford study also found that approximately 30 percent of baby boomers had no money saved in retirement plans in 2014, when they were age 58, on average, “leaving them little time to start saving for retirement.” And, the median balance for those who held a retirement account was only $200,000, far too small an amount to generate the income needed to carry a person through a 20- to 30-year retirement.

Looking just at retirement age boomers, a 2018 PBS News Hour report noted that:

Nearly half of Americans nearing retirement age (65 years old) have less than $25,000 put away, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute’s annual survey. One in four don’t even have $1,000 saved.

Adding to the retirement nightmare is the fact that many boomers also remain deep in debt. A CNBC story reports that:

One-third of homeowners over the age of 65 were still paying off a mortgage in 2012, compared with less than a quarter of people in 1998 — and the median amount they owed nearly doubled to $82,000 from $44,000.

Meanwhile, the number of people aged 60 and older with student debt quadrupled between 2005 and 2015, to 2.8 million from 700,000.

One reason for low boomer financial balances is that this generation was hit hard by the Great Recession and the following years of low interest rates, and has yet to recover. Boomer median household net worth was $224,100 in 2007 and only $184,200 in 2016.

African American and Latinx baby boomers face even greater problems, earning less money and having far less retirement savings than white Americans. Accordin g to Forbes, “The average white family had more than $130,000 in liquid retirement savings (cash in accounts such as 401(k)s, 403(b)s and IRAs) vs. $19,000 for the average African American in 2013, the most recent data available.”

Latinx retirement savings also trails that of whites. For example, in 2014, among working individuals age 55 to 64, only 32.2 percent of Latinx had money in a retirement account compared with 58.5 percent of whites. The average Latinx account held $42,335 while the average white account held $103,526.

With private pensions and personal savings inadequate to fund a secure retirement, it is no wonder that so many boomers strongly defend Social Security, the so-called third leg (in addition to private pensions and personal savings) of the retirement “stool.” But, as important as it is, the average Social Security check in 2018 was only $1,422 a month or $17,064 a year.

It should therefore come as no surprise that research by the Institute on Assets and Social Policy finds that one-third of seniors have no money left over at the end of the month or are in debt after meeting necessary expenses. Or that growing numbers of seniors are making the decision to forego retirement altogether, by either continuing to work to returning to the labor force.

Saying goodbye to retirement

According to the 2019 report titled Boomer Expectations for Retirement, one-third of boomers plan to retire at age 70 or not at all. And one-third of employed boomers ages 67-72 postponed retirement.

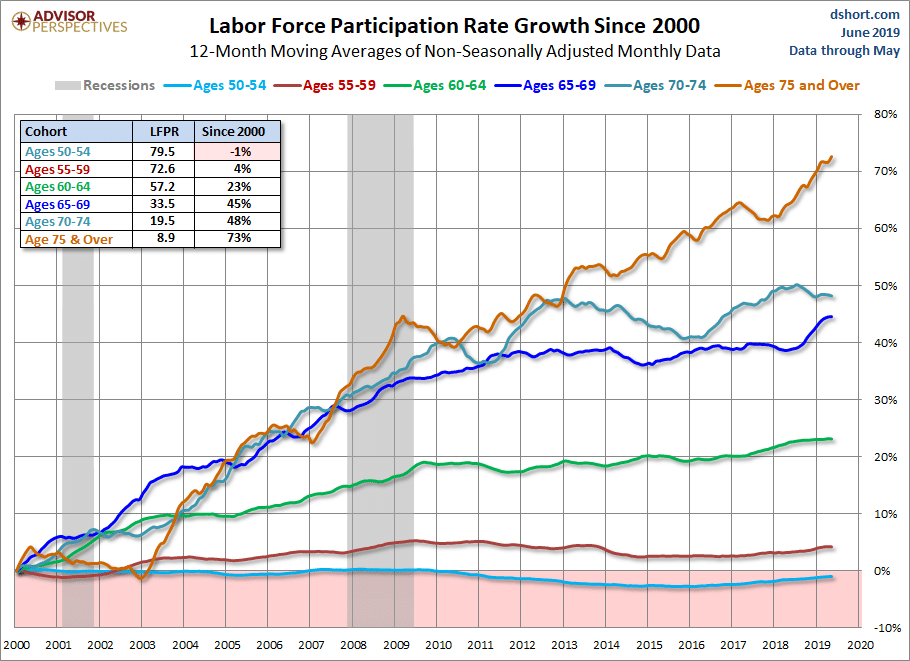

Thus, while labor force participation rates are declining for many age cohorts, they are growing for boomers and older workers. In fact, between April 2000 and January 2018, “there has been essentially no net growth of employment for workers under age 55. Over that same time, employment for workers over age 55 has doubled.”

The figure below shows labor force participation rates for six age 50-plus cohorts since the turn of the century. As Jill Mislinski states: “The pattern is clear: The older the cohort, the greater the growth.”

Sadly, many of these older workers have had little choice but to accept low-paid, physically demanding work at some of America’s richest companies (e.g., Walmart and Amazon) who are delighted to take advantage of their desperation.

Sadly, many of these older workers have had little choice but to accept low-paid, physically demanding work at some of America’s richest companies (e.g., Walmart and Amazon) who are delighted to take advantage of their desperation.

Jessica Bruder’s 2017 book, Nomadland: Survival in Twenty First Century America, describes mostly white baby boomers who, strapped for money, decide to buy used RVs and travel. We learn about the friendships they make, and also the minimum wage seasonal jobs they are forced to take to survive. Zhandarka Kurti draws on Bruder’s work to highlight their experience with Amazon:

With its motivational slogan of “work hard, have fun, make history,” Amazon recruits seasonal workers at various “nomad friendly events” including “RV shows and rallies—in more than a dozen states across America.” Older workers are drawn to the opportunity to make good money in a relatively short time. . . . Also ironically, Walmart and Amazon, the two competing retail giants and also the country’s largest employers, allow their workers to park overnight, an attractive perk for many older nomads who struggle with food security let alone rent. . . .

While most of the nomads are made aware of the physical aspects of the job [working in Amazon fulfillment centers] during the training seminars, they are nonetheless surprised by just how much pain they are in after a day’s work. . . . Older workers constantly complain of chronic pain from work and Amazon’s solution is to offer free over-the-counter pain killers. . . . Amazon leaves older workers so physically tired that they have little occasion to enjoy their leisure time. Instead they spent the remainder of their “free” time nursing themselves back to health to survive another workday. . . .

In many ways older workers are Amazon’s dream labor force. “They love retirees because we’re dependable. We’ll show up and work hard, and are basically slave labor” one 78 year-old workamper who previously worked as a teacher in California’s community colleges confides in Bruder. Older workers are what Bruder calls “plug-and-play labor” in that they are only around for a short time, are often too tired to complain about the non-existent benefits and are generally appreciative of the jobs regardless of the pain they endure. . . . Amazon also receives federal tax credits to hire older disadvantaged workers and the company predicts that by 2020 one in every four workampers in the U.S. would have worked for Amazon.

It is clear that leading American businesses do not favor bringing back pensions, or boosting wages, or paying higher taxes to strengthen and expand social security and other social services. Thus, if existing trends are not challenged and reversed, the boomer generation (or at least a significant minority) may well be the last to experience some sort of satisfactory retirement. This development is yet another sign of a failed system. Boomers need to find ways to help younger generations keep the goal of a satisfying retirement alive, and join in a common fight for the structural changes required to realize it.