Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Millions of people are on the streets, from India to Chile. Democracy is both their promise and it is what has betrayed them. They aspire to the democratic spirit but find that democratic institutions–saturated by money and power–are inadequate. They are on the streets for more democracy, deeper democracy, a different kind of democracy.

Sharply, in each and every region of India, ordinary people unaffiliated to political parties alongside the Indian Left have taken to the streets to demand the withdrawal of a fascistic law that would turn Muslims into non-citizens. This immense wave rises even when the government tries to declare demonstrations illegal, and even as the government shuts down the Internet. Twenty people have been killed by the police forces thus far. None of this stopped the people, who declared loudly that they would not accept the suffocation of the Far Right. This continues to be an unanticipated and overwhelming uprising of the population.

Democracy has been shackled by capitalist power. If sovereignty were merely about numbers, then the workers and the peasants, the urban poor and the youth would be represented by people who put their interests first and would be able to command more of the fruit of their labour. Democracy promises that people would be able to control their destiny. Capitalism, on the other hand, is structured to allow the capitalists–the property owners–to have power over the economy and society. From the standpoint of capitalism, democracy’s full implications cannot be allowed. If democracy gets its way, then the means of producing wealth would be democratised; this would be an outrage against property, which is why democracy is narrowed.

Systems of liberal democracy grow around the State, but these systems cannot be allowed to become too democratic. They are to be held back in check by the repressive apparatus of the State, which claims to constrain democracy in the name of ‘law and order’ or security. Security or ‘law and order’ become the barriers to full democracy. Rather than say that the defence of property is the goal of the State, it is said that the State’s goal is to maintain order, which comes to mean an association of the widest democratic practices with hooliganism and criminality. To demand an end to the private appropriation of social wealth–which is itself theft–is called theft; it is the socialists, not the capitalists, who are defined as criminals not against Property but against Democracy.

By this sleight of hand, through the financing of private media and other institutions, the bourgeoise is able to convincingly show that it is the defender of democracy; and therefore, it comes to define democracy as merely elections and the free press–which can both be purchased as just another commodity–and not the democratisation of society and economy. Both social and economic relations are left outside the dynamic of democracy. Trade unions–the instrument for the democratisation of economic relations–are disparaged openly and their rights curtailed; social and political movements are defanged, and NGOs emerge, with the NGOs often narrowing their agenda to small reform rather than to challenge the property relations.

As a result of the wall between elections and economics, between reducing politics to elections and preventing the democratisation of the economy, looms a sense of futility. This is illustrated by the crisis of liberal democracy’s representational framework. Decreased voter turnouts are one symptom, but others include the cynical use of money and the media to divert attention from any substantial discussion about real problems into fantasy problems, from finding common problems to social dilemmas to inventing false problems about society. The use of divisive social issues allows for a diversion from the issues of hunger and hopelessness. This is what the Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch called the ‘swindle of fulfilment’. The benefit of social production, Bloch wrote, ‘is reaped by the big capitalist upper stratum, which employs gothic dreams against proletarian realities’. The entertainment industry erodes proletarian culture with the acid of aspirations that cannot be fulfilled under the capitalist system. But these aspirations are enough to push aside any working-class project.

As a result of the wall between elections and economics, between reducing politics to elections and preventing the democratisation of the economy, looms a sense of futility. This is illustrated by the crisis of liberal democracy’s representational framework. Decreased voter turnouts are one symptom, but others include the cynical use of money and the media to divert attention from any substantial discussion about real problems into fantasy problems, from finding common problems to social dilemmas to inventing false problems about society. The use of divisive social issues allows for a diversion from the issues of hunger and hopelessness. This is what the Marxist philosopher Ernst Bloch called the ‘swindle of fulfilment’. The benefit of social production, Bloch wrote, ‘is reaped by the big capitalist upper stratum, which employs gothic dreams against proletarian realities’. The entertainment industry erodes proletarian culture with the acid of aspirations that cannot be fulfilled under the capitalist system. But these aspirations are enough to push aside any working-class project.

It is in the interest of the bourgeoisie to destroy any working-class and peasant project. This can be done by the use of violence, the law, and by the swindle of fulfilment, namely the creation of aspirations within capitalism that destroy the political platform for a post-capitalist society. Parties of the working-class and peasantry are mocked for their failure to produce a utopia within the boundaries of capitalism; they are mocked for their projects which are said to be unrealistic. The swindle of fulfilment, the gothic dreams, are seen as realistic, whereas the necessity of socialism is portrayed as unrealistic.

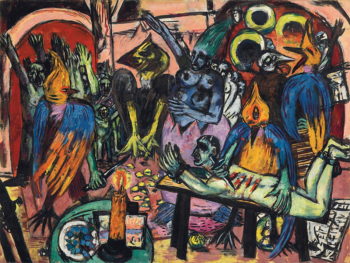

Max Beckmann, Hölle der Vögel, 1937-38.

The bourgeois order does, however, have a problem. Democracy requires mass support. Why would the masses support parties that have an agenda that does not fulfil the immediate needs of the working-class and the peasantry? It is here that culture and ideology play important roles. ‘Swindle of fulfilment’ is another way of thinking about hegemony–the arc of how the social consciousness of the working class and the peasantry is shaped not only by their own experiences, which allow them to recognise the swindle, but also by the ruling class ideology that whips into their consciousness through the media, through educational institutions, and through religious formations.

The swindle is magnified when the basic structures of social welfare–pushed by the people onto the agenda of governments–are cut to bits. To ameliorate the harshness of social inequality that results from the private appropriation of social wealth by the bourgeoisie, the State is forced by the people to create social welfare programmes–public health and public schools, as well as targeted schemes for the indigent and the working poor. If these are not available people will begin to die–in larger numbers–on the streets, which would call into question the swindle of fullfilment. But, as a consequence of the long-term crisis of profitability, these schemes have been cut over the past several decades. The outcome of this crisis of liberal democracy due to the neoliberal policy of austerity is high economic insecurity and growing anger at the system. A crisis of profitability becomes a crisis of political legitimacy.

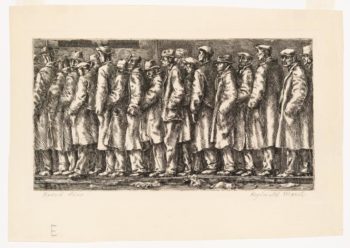

Reginald Marsh, Bread Line – No One Has Starved, 1932.

Democracy is a game of numbers. Oligarchies are forced by the establishment of democratic systems to respect the fact that the masses must participate in political life. The masses must be political, but–from the standpoint of the bourgeoisie–they must not be permitted to control the political dynamic; they must be political and de-politicised at the same time. They must be agitated sufficiently, but not agitated so much so that they challenge the membrane that protects the economy and society from democracy. Once that membrane is breached, the fragility of capitalist legitimacy ends. Democracy cannot be allowed into the arena of the economy and of society; it must remain at the level of politics, where it must be restricted to electoral processes.

Regimes of austerity hurt the lives of the masses. They cannot be deluded into the belief that they are not suffering from cuts and from joblessness. Austerity washes away the fog of delusion; the swindle of fulfilment is no longer as compelling as it was before the cuts sliced away at basic necessities. The bourgeoisie prefers that the people are consolidated into ‘masses’ and not ‘classes’, into indistinct groups of a variety of conflicting interests that can be shaped according to the framework produced by the bourgeoisie rather than by their own class positions and interests. Whereas neoliberals see their political project exhausted as their own dreams of fulfilment around terms such as ‘entrepreneurship’ become nightmares of unemployment and bankruptcy, the Far Right emerges as the champion of the moment.

The Far Right is uninterested in the complexities of the moment. It does address the main social problems–unemployment and insecurity–but it does not look at the context of these problems or look closely at the actual contradictions that have to be engaged so that the people can overcome them. The actual contradiction is between social labour and private accumulation; the unemployment crisis cannot be solved unless this contradiction is resolved on behalf of social labour. Since that is unspeakable for the bourgeoisie, it no longer seeks to resolve the contradiction but settles for a ‘bait and switch’ strategy–it is acceptable to talk of unemployment, for instance, but there is no need to blame private capital for that; instead, blame migrants, or other scapegoats.

To accomplish this ‘bait and switch’, the Far Right has to go against another seam of thought in classical liberalism: the protection of minorities. Democratic Constitutions have all been aware of the ‘tyranny of the majority’, setting barriers to majoritarianism through laws and regulations that protect minority rights and cultures. These laws and regulations have been essential for the widening of democracy in society. But the Far Right’s democracy is premised not on these protections but on their destruction. It seeks to inflame the majority against the minority in order to bring the masses onto its side, but not to allow the classes within them to develop their own politics. The Far Right has no fealty to the traditions and regulations of liberal democracy. It will use the institutions as long as they are useful, poisoning the culture of liberalism which had serious limitations, but which at least provided space for political contestation. That space is now narrowing as a very violent defence of the Far Right is increasingly becoming legitimised.

V. Arun Kumar (People’s Dispatch), Rapid Action Force, Delhi, 19 December 2019.

Minorities are disenfranchised in the name of democracy; violence is let loose in the name of the feelings of the majority. Citizenship is narrowed around the definitions of the majority; people are told to accept the culture of the majority. This is what the BJP government has done in India with the Citizenship (Amendment) Act of 2019. It is what the people reject.

By the swindle of majoritarianism, the Far Right can appear to be democratic when it operates to protect the membrane between politics (merely in the electoral sense) and society, as well as the economy. The protection of this membrane is essential, the abolishment of any potential expansion of democracy into society and the economy forbidden. The fiction of democracy is maintained as the promise of democracy is set aside.

It is this promise that provokes the people onto the streets in India, Chile, Ecuador, Haiti, and elsewhere. From all of us at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, see you on the streets, and happy new year.

Warmly, Vijay.