Dear Friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Madness engulfs the planet. Hundreds of millions of people are in lockdown in their homes, millions of people who work in essential jobs–or who cannot afford to stay home without state assistance–continue to go to work, thousands of people lie in intensive-care beds taken care of by tens of thousands of medical professionals and caregivers who face shortages of equipment and time. Narrow sections of the human population–the billionaires–believe that they can isolate themselves in their enclaves, but the virus knows no borders. The global pandemic driven by the variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus holds us in its grip; even as China seems to have bent the curve of infections, the charts for the rest of the world are forbidding: the light at the end of the tunnel is as dim as it has ever been.

Incompetent and heartless governments put the hammer down on society without any planning or concern for those with few resources. It is one thing for the elite or the middle class to stay at home, work using the Internet, and muddle through teaching their children from home; it is another for the billions of migrant labourers and day labourers, people who live hand to mouth, and people who have no homes. Lockdowns, quarantines, social distancing–these words mean nothing for the billions of people who work hard each day to socially reproduce the world and to produce the millions of commodities; they have not benefited from their work, but they have certainly enriched the few who are now hiding with their wealth behind their curtains, afraid of the reality that made them rich.

Italian author Francesca Melandri’s ‘Letter to the French from the Future’ (Libération, 18 March) says, ‘Class will make all the difference. Being locked up in a house with a pretty garden is not the same as living in an overcrowded housing project. Nor is being able to work from home or seeing your job disappear. The boat in which you’ll be sailing in order to defeat the epidemic will not look the same to everyone nor is it actually the same for everyone: it never was’. Her judgment is mirrored by OluTimehin Adegbeye, who looks at the six million daily wage workers in her city of Lagos (Nigeria); if they survive the coronavirus, they will perish from hunger (and, amongst them, the most at risk are women and girls who will be tending to the sick in their families and–like medical personnel–will likely catch the coronavirus in large numbers). In South Africa, the state is threatening to evict workers from shacks, saying that they need to break up these congested areas; Axolile Notywala from Ndifuna Ukwazi of Cape Town says, ‘De-densification is just a fancier word for forced eviction’. This is what is happening to the global working class in this CoronaShock.

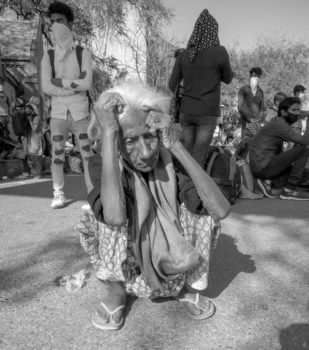

The display of disparities condenses at the Anand Vihar bus terminal in Delhi (India), where thousands of factory workers and service sector workers stood cheek-by-jowl as the country closed down. P. Sainath, our Senior Fellow, writes that ‘the only transportation now available’ to the working class is ‘their own feet. Some are cycling home. Several find themselves stranded midway when trains, buses, and vans stop functioning. It’s scary, the kind of hell that might break loose if this intensifies. Imagine large groups walking home, from cities in Gujarat to villages in Rajasthan; from Hyderabad to far-flung villages of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh; from Delhi to places in Uttar Pradesh, even Bihar; from Mumbai to no-one-knows-how-many destinations. If they receive no succour, their rapidly diminishing access to food and water could trigger a catastrophe. They might fall to age-old diseases like diarrhoea, cholera, and others’.

Neeraj Kumar, age 30, works at a cloth factory, where workers are paid on a piece-rate basis. ‘We have no money left’, he told The Wire. ‘I have two children. What will I do? We live in rented accommodation and did not have any money or food left’. He will have to go to Budaun, two hundred kilometres away. Mukesh Kumar is from Madhubani (Bihar) and has a 1,150-kilometre journey ahead of him. He worked at a food outlet, where he used to get food as part of his wages. But the outlet is closed. ‘I have no money left’, he said. ‘I have no one here who would look after me if I get infected. So, I am leaving’.

The Delhi office of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research did a survey of garment workers, most of whom do not have permanent jobs. ‘We are here for work’, one worker told us. ‘We left our families in our villages. We try to work as much as possible to earn that little extra income to feed and support our families’. Three-quarters of the workers we interviewed said that they are the only wage-earning member in their family; the agrarian crisis has beaten down the earning capacity of their families, who rely on remittances from these migrant workers, even though they themselves provide unpaid labour for the social reproduction of family life in the village. Now it is these workers–with no state support–who are marching back home, some carrying the coronavirus, back into the heart of the agrarian crisis.

Umesh Yadav, a researcher at Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research, wrote as these masses of workers left Delhi: ‘These migrant workers did not suddenly fall from the sky. They have existed on the peripheries of the cities, in the ghettos and the slums; they are deliberately kept invisible and unnoticed by the elite’. A hasty show of compassion for them as they form long lines on the roads that leave the cities is not enough; the system that uses them, keeps them barely alive, and then throws them out must be struggled against, another system put in its place. The hideousness of social inequality produces a heap of sorrow and anger amongst the damned of the earth.

What happens when the government tells three hundred million casual workers to sit at home for three weeks after they have made their long exodus? These are workers who have never been paid enough to save, and who have few resources to sustain themselves during this period. It is essential for the government to organise the provision of food through public distribution systems and through free canteens (as pointed out by Subin Dennis of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research). If there are no such schemes, the global pandemic will lead to widespread hunger and famine. It might also lead to a deepening crisis in the countryside, as the winter (rabi) crops such as mustard, pulses, rice, and wheat might not be properly harvested due to a labour shortage occasioned by the lockdown. A failure of the winter crops in India would be cataclysmic.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) estimates that at least 25 million people across the world will lose their jobs due to the coronavirus, and that they will lose income worth about $3.4 trillion. But, as the ILO’s Director-General Guy Ryder correctly said, ‘it is already becoming clear that these numbers may underestimate the magnitude of the impact’. There were already 71 million displaced people before the CoronaShock–one person displaced every two seconds. Numbers are bewilderingly difficult to estimate–how many people will lose everything, with nothing from any of these ‘stimulus packages’ trickling down to them? These enormous infusions of trillions of dollars trickle down from central banks into the coffers of financial institutions and large corporations and into the vaults of the billionaires. By some miracle, the money that falls from heaven gets stuck in the penthouses. None of the hundreds of millions who will find their lives disjointed will be able to catch any of that money because none of it will reach them.

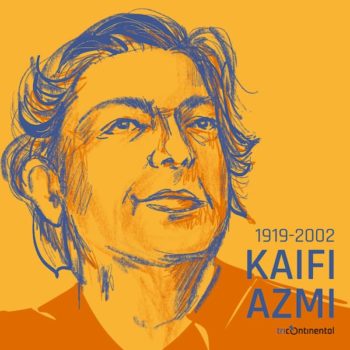

Kaifi Azmi (1919-2002) whose verses dug deep into the soil of the Indian peasantry and workers, wrote a sublime poem called Makaan (House), which is a song of the construction workers:

Kaifi Azmi (1919-2002) whose verses dug deep into the soil of the Indian peasantry and workers, wrote a sublime poem called Makaan (House), which is a song of the construction workers:

Once the palace was built, they hired a guard to keep us out.

We slept in the dirt, with the sound of our craft;

Our heartbeat pounding with exhaustion,

Bearing the picture of the palace we built in our tightly shut eyes.

The day still melts on our heads like before,

The night pierces our eyes with black arrows,

A hot air blows tonight.

It will be impossible to sleep on the pavement.

Arise everyone! I will rise too. And you. And you too.

So that a window may open in these very walls.

Kerala–the state governed by the Left Democratic Front–is a window in the ghastly wall. The government is opening thousands of camps for migrant workers in Kerala who would need accommodation. As of 28 March, 144,145 migrant workers had been housed in 4,603 camps, and more camps are being opened. The government is also building camps for homeless and destitute people–44 camps have been opened so far in which 2,569 people are staying. The state has opened community kitchens across the state to provide free hot meals; for those who cannot come to the kitchens, the food is delivered to their homes.

Please break the walls and build windows.

Warmly, Vijay.