The announcement by the Bureau of Labor Statistics that the federal unemployment rate declined to 13.3 percent in May, from 14.7 percent in April, took most analysts by surprise. The economy added 2.5 million jobs in May, the first increase in employment since February. Most economists had predicted further job losses and a rise in the unemployment rate to as high as 20 percent.

This employment gain has encouraged some analysts, especially those close to the Trump administration, to proclaim that their predicted V-shaped economic recovery had begun. But there are strong reasons to believe that the U.S. economy is far from recovery.

Long term trends and the coronavirus

Predictions for a V-shaped recovery rest to a considerable degree on the belief that our current economic collapse was caused by state mandated business closures to battle the coronavirus which unsurprisingly choked off our long expansion. Now that a growing number of states are ending their forced lockdowns it is only natural that the economy would resume growing. Certainly, the stock market’s recent rise suggests that many investors agree.

However, there are many reasons to challenge this upbeat story of impending recovery. One of the most important is that the pre-coronavirus period of expansion (June 2009 to February 2020), although the longest on record, was also one of the weakest. It was marked by slow growth, weak job creation, deteriorating job quality, declining investment, rising debt, declining life expectancy, and narrowing corporate profit margins. In other words, the economy was heading toward recession even before the start of state mandated lockdowns. For example, the manufacturing sector spent much of 2019 in recession.

Another reason is that the downturn in economic activity that marks the start of our current recession predates lockdown orders. It was driven by health concerns. As Emily Badger and Alicia Parlapiano explain in their New York Times article, and as illustrated in the following graphic taken from the article:

In the weeks before states around the country issued lockdown orders this spring, Americans were already hunkering down. They were spending less, traveling less, dining out less. Small businesses were already cutting employment. Some were even closing shop.

People were behaving this way–effectively winding down the economy–before the government told them to. And that pattern, apparent in a range of data looking back over the past two months, suggests in the weeks ahead that official pronouncements will have limited power to open the economy back up.

In some states that have already begun that process, like Georgia, South Carolina, Oklahoma and Alaska, the same daily economic data shows only meager signs so far that businesses, workers and consumers have returned to their old routines.

Thus, while some rebound in economic growth is to be expected given the severity of the downturn to this point, it is unlikely that the May employment jump signals the start of a powerful economic recovery. Weak underlying economic conditions and health worries remain significant obstacles.

In fact, even the optimistic U.S. Congressional Budget Office predicts at best a long, slow recovery. As Michael Roberts describes:

It now expects U.S. nominal GDP to fall 14.2% in the first half of 2020, from the trend it forecast in January before the COVID-19 pandemic broke. Then it expects the various fiscal and monetary injections by the authorities and the end of the lockdowns to reduce this loss from the January figure to 9.4% by end 2020. The CBO still expects a sort of V-shaped recovery in U.S. GDP in 2021 but does not expect the pre-pandemic crisis trend in U.S. economic growth (already reduced in the Long Depression since 2009) to be reached until 2029 and may not even return to the previous trend growth forecast until after 2030! So there will be a permanent loss of 5.3% in nominal GDP compared to pre-COVID forecasts–$16trn in value lost forever. In real GDP terms, the loss will be about 3% cumulatively, or $8trn in 2019 money. And this assumes no second wave in the pandemic and no financial collapse as companies go bust.

Depression level unemployment

Although President Trump has celebrated the May employment gains, the fact is we continue to suffer depression level unemployment. The following figure from the Washington Post provides some historical perspective. The current official unemployment rate of 13.3 percent is more than a third higher than the highest level of unemployment reached during the Great Recession.

But even the Bureau of Labor Statistics acknowledges that because of the unique nature of the current crisis the official announced unemployment rate for each of the last three months is flawed. The unemployment rate is based on household surveys. For the past three months, in an attempt to better understand the impact of the coronavirus, interviewers were supposed to classify people not working because of the virus as “unemployed on temporary layoff.” However, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics acknowledges, many of those people were incorrectly classified as “employed but absent at work,” which is the classification used when a person isn’t coming to work because of vacation, illness, bad weather, a labor dispute, or other reasons. People in this latter category are not counted as unemployed.

The BLS has determined that correcting the classification error would boost the official April unemployment rate to 19.7 percent and the May rate to 16.3 percent. And, it is important to note that this unemployment rate does not include those workers who have stopped looking for work and those who are involuntarily working part-time. Including them would push the May rate close to 25 percent.

Stephen Moore, an economic adviser to President Trump, has stated that the May job numbers take “a lot of the wind out of the sails of any phase 4 [stimulus bill]–we don’t need it now. There’s no reason to have a major spending bill. The sense of urgent crisis is very greatly dissipated by the report.” This is crazy.

Danger signs ahead

There are three reasons to fear that without substantial new federal action May employment gains will be short-lived.

First, it has been relatively low-wage production and nonsupervisory workers who have suffered the greatest number of job losses. That has left many businesses relatively top-heavy with managers and high-income professionals. A number of business analysts are now predicting a new wave of layoffs or firings of higher-income and management personal to bring staffing levels back into pre-coronavirus balance.

The following figure shows that almost 90 percent of the jobs lost from mid-February to mid-April were in the six lowest paid supersectors as defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. The May employment gains were also in these six sectors.

Economists with Bloomberg Economics are now warning of a second wave of job losses that will include “higher-paid supervisors in sectors where frontline workers were hit first, such as restaurants and hotels. It also includes the knock on-effects to connected industries such as professional services, finance and real estate.”

As Bloomberg explains:

The pandemic isn’t finished with the U.S. labor market, threatening a second wave of job cuts—this time among white-collar workers. . . .

For the analysis, [Bloomberg Economics economists] looked at job losses by sector in March and April—with affected industries dominated by blue-collar, hospitality and production workers—and determined how those layoffs would move to supervisory positions, since management cuts tend to lag the frontline workers.

The economists then took government data on relations between industries to compute the ones most reliant on demand from the most-affected sectors. Combining that information with the hit to employment in the most affected sectors they extrapolated to other jobs at risk, most of which were higher-skilled, white-collar roles.

The second reason to downplay the significance of the May employment gains is that critically important stimulus measures–in particular the one-time grant of $1200 for individuals and the $600 a week additional unemployment benefit (which expires at the end of July)–appear unlikely to be renewed. If that boost to earnings is withdrawn, economic demand and employment will likely fall again.

As Ben Casselman, writing in the New York Times, points out:

Research routinely finds that unemployment insurance is one of the most effective parts of the safety net, both in cushioning the effects of job loss on families and in lifting the economy. In economists’ parlance, the program is “well targeted”–it goes to people who need the money and who will spend it. Various studies have found that in the last recession, the system helped prevent 1.4 million foreclosures, saved two million jobs and kept five million people out of poverty.

The impact could be greater in this crisis because the program is reaching more people and giving them more money. The government paid $48 billion in benefits in April and has reached $86 billion in May, according to the Treasury Department.

As the following figure shows, almost all workers have suffered significant declines in employment income with low income workers taking the biggest hit.

Yet, the increase in food insecurity has been relatively small, especially for low income workers.

It is, as highlighted in the next figure, the massive individual benefit boosts included in the March stimulus package that has so far kept the decline in employment income from translating into dramatic spikes in food insecurity. If Congress refuses to pass a new stimulus that includes direct aid to the unemployed, the odds are great that the economic recovery will stall and unemployment will grow again.

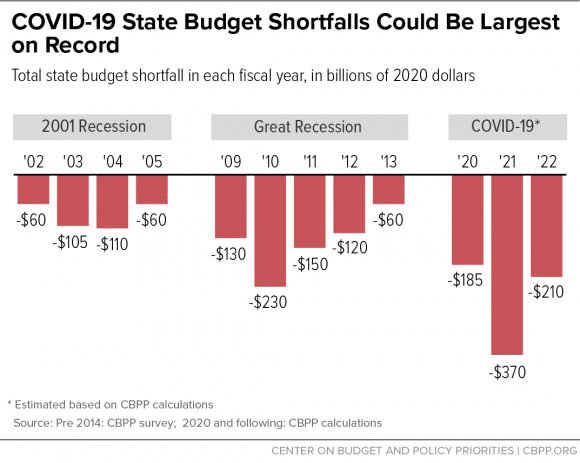

The last reason for pessimism is the likely further contraction in state and local government spending and, by extension, employment and services, as a result of declining revenue. State and local government employment fell by 1 million from February to April, and by an additional 600 million in May. Looking just at state budgets, the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities estimates a shortfall in state budgets of $765 billion over fiscal years 2020-22, “much deeper than in the Great Recession of about a decade ago” (see the figure below).

And unfortunately, as the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities also notes, the federal government has, up to now, been unwilling to do much to help state governments manage their ballooning deficits:

Federal aid that policymakers provided in earlier COVID-19 packages isn’t nearly enough. Only about $65 billion is readily available to narrow state budget shortfalls. Treasury Department guidance now says that states may use some of the aid in the CARES Act of March to cover payroll costs for public safety and public health workers, but it’s unclear how much of state shortfalls that might cover; existing aid likely won’t cover much more than $100 billion of state shortfalls, leaving nearly $665 billion unaddressed. States hold $75 billion in their rainy-day funds, a historically high amount but far too little to meet the unprecedented challenge they face. And, even if states use all of it to cover their shortfalls, that still leaves them about $600 billion short.

States must balance their budgets every year, even in recessions. Without substantial federal help during this crisis, they very likely will deeply cut areas such as education and health care, lay off teachers and other workers in large numbers, and cancel contracts with many businesses. . . . That would worsen the recession, delay the recovery, and further harm families and communities.

Without a new stimulus measure that also includes support for state and local governments, their forced reduction in spending and cuts in employment can only add to the existing pressures working against recovery.

In sum, the crisis is real. A new stimulus that included a renewal of special unemployment payments as well as direct support for state and local governments and other critical services like the postal service could help stabilize the economy. But real progress will require a major effort on the part of the federal government to ensure adequate production of COVID-19 test kits and PPE as well as nationwide testing and contact tracing programs and then, most importantly, a fundamental reorganization of our economy.