We need strong unions, all of us. Tragically, even during the pandemic, businesses continue to aggressively resist worker attempts at unionization. And recent decisions by the NLRB only add to worker difficulties.

Here is one example of what is at stake: a recently published study of New York State nursing homes found that mortality rates from COVID-19 were 30 percent lower in unionized nursing homes than in facilities without health care worker unions. By gaining better protection for themselves, unionized workers were also able to better protect the health of those they served.

Although the pandemic makes organizing and solidarity actions more difficult, it is essential that we find effective ways to support worker struggles for strong unions.

Work during the pandemic

Many workers, especially those now celebrated as “essential” or “frontline,” don’t feel safe at work, and for good reason. Many have been denied needed personal protective equipment (PPE) or even information about the health status of their coworkers.

While surveys find that many employers have implemented new workplace cleaning procedures, they also find that a large percentage of workers continue to work without access to PPE, especially masks and gloves. Strikingly, according to one study,

If [worker] access to PPE was limited in our data, policies mandating that workers wear protective gear were even more uncommon. Around a third of workers in restaurants, fast food, coffee shops, and hotels and motels reported requirements to wear gloves. This share was dramatically lower (around 12%) in big-box stores, department stores, retail stores, grocery stores, and pharmacies. The share of workers required to wear gloves was even lower in warehouses, fulfillment centers, and in delivery. Mask requirements were vanishingly uncommon across workplaces, at between 2% and 7% in convenience stores, coffee shops, fast food, restaurants, grocery stores, retail, department stores, and big-box stores. Just 12% of those in fulfillment centers reported a mask requirement, which was significantly higher than the 5% of warehouse and delivery workers.

Adding to the danger, many companies are aggressively trying to keep information about worker infections secret from coworkers and the public. As a Bloomberg Law post explains:

U.S. businesses have been on a silencing spree. Hundreds of U.S. employers across a wide range of industries have told workers not to share information about COVID-19 cases or even raise concerns about the virus, or have retaliated against workers for doing those things, according to workplace complaints filed with the NLRB and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

Workers at Amazon.com, Cargill, McDonald’s, and Target say they were told to keep Covid cases quiet. The same sort of gagging has been alleged in OSHA complaints against Smithfield Foods, Urban Outfitters, and General Electric. In an email viewed by Bloomberg Businessweek, Delta Air Lines told its 25,000 flight attendants to “please refrain from notifying other crew members on your own” about any Covid symptoms or diagnoses. At Recreational Equipment Inc., an employee texted colleagues to say he’d tested positive and that “I was told not to tell anybody” and “to not post or say anything on social media.”

These policies may help the corporate bottom line, but they endanger workers and those they serve, and thereby help to spread the pandemic.

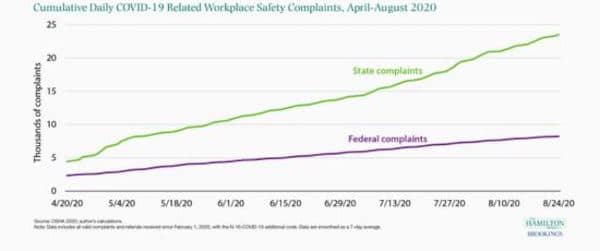

Without unions, workers have limited ways to force their employers to create a safe work environment. One is to file a complaint with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. And, despite fears of retaliation, many workers have done just that. As a Brookings blog post reports:

Using data from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), [the figure below] shows the cumulative number of COVID-19 related workplace safety complaints. Between April 20 and August 20, total COVID-19 related workplace safety complaints rose over 350 percent.

Unfortunately, these complaints have achieved little. According to the Bloomberg Law post, “ Many thousands of OSHA complaints about coronavirus safety issues have yielded citations against just two companies—a health-care company and a nursing home—totaling about $47,000.” OSHA has still not issued any regulations that address the pandemic.

OSHA rarely sends out inspectors to investigate complaints. The Bloomberg Law post describes one case in which a mechanic at Maid-Rite, a company that supplies frozen meat products to military bases, nursing homes, and schools, wrote to OSHA describing unsafe conditions:

The mechanic says OSHA called him to say it would be sending Maid-Rite a letter instead of coming to inspect the plant, and that was the last he ever heard from the agency about his complaint. Letters between OSHA and Maid-Rite show OSHA told Maid-Rite in April to investigate worker allegations itself, and Maid-Rite wrote back saying that it was providing and mandating masks and that 6-foot distancing sometimes wasn’t feasible.

No changes were made and so other workers followed up with more complaints over the following weeks, leading OSHA to finally send an inspector to the plant. However,

in a break from typical protocol, [the inspector] gave the company a heads-up. “OSHA is here, so do everything right!” a supervisor told staff during the inspection, the mechanic later wrote in an affidavit. Fifteen minutes later, the supervisor returned to say “Never mind,” because the visit was over, the mechanic wrote: “As soon as OSHA left, everything went exactly back to the way it was.”

Unions can help

Unions are far from perfect, but they are one of the most effective means workers have to protect their interests, and by extension those they serve. That point is highlighted by the results of the above noted study on COVID-19 deaths in nursing homes which found that mortality rates from COVID-19 are lower in unionized nursing homes. This is significant because approximately 43% of all reported COVID-19 deaths in the United States have occurred in nursing homes.

The three authors–Adam Dean, Atheendar Venkataramani, and Simeon Kimmel–focused on nursing homes in New York State, which has had over 6,500 COVID-19 nursing home deaths, second only to New Jersey. The authors built a model that attempted to explain the variation in confirmed COVID-19 deaths at these New York State nursing homes with an eye to determining if the presence of a health care union made a difference. They used “proprietary data from 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, and the Communication Workers of America (CWA), as well as publicly-available data from the New York State Nurses Association (NYSNA) to determine if a labor union represented health care workers in each facility.”

Their cross-section regression model also included a range of nonunion variables as possible causes for the variation. These variables included: whether or not a facility had an adequate supply of PPEs, including masks, eye shields, gowns, gloves, and hand sanitizer; the average age of residents; Resource Utilization Group Nursing Case Mix Index of resident acuity, which classifies patient care needs based on diagnosis, proposed treatment, and level of needed assistance with activities of daily living; occupancy rates; staff-hours-to resident-days ratios for RN, CNA, and licensed practical nurses; percent of residents whose primary support comes from Medicaid or Medicare; Overall 5-Star Rating; whether the nursing home was part of a chain; whether the nursing home was for-profit or non-profit; and county-level data on confirmed cases of COVID-19 and population.

Their main regression result, confirmed by several sensitivity tests, was that, taking all the other variables into account, the presence of a health care labor union was associated with a 30% relative decrease in the COVID-19 mortality rate compared to facilities without a health care labor union.

In examining possible reasons for this result, they ran two other regressions. One found that the presence of a health care labor union was associated with a 13.8% relative increase in access to N95 masks and a 7.3% relative increase in access to eye shields. Labor union status was not a significant predictor of access to other types of PPE. The other regression found that the presence of a health care labor union was associated with a 42% relative decrease in the COVID-19 infection rate.

The struggle ahead

There is good reason to believe that the union benefits found by Dean, Venkataramani, and Kimmel in their study are not limited to New York State nursing homes. Unions are one of the most effective ways for workers to ensure access to critical PPEs and implementation of safety regulations, things that as noted above workers desperately seek.

But of course, corporations don’t want to pay the higher costs that come with unionization. They prefer the status quo, where working people are forced to pay far greater costs, individually and collectively. And even in the midst of the pandemic, the NLRB continues to pass new rules making it ever more difficult for workers to unionize.

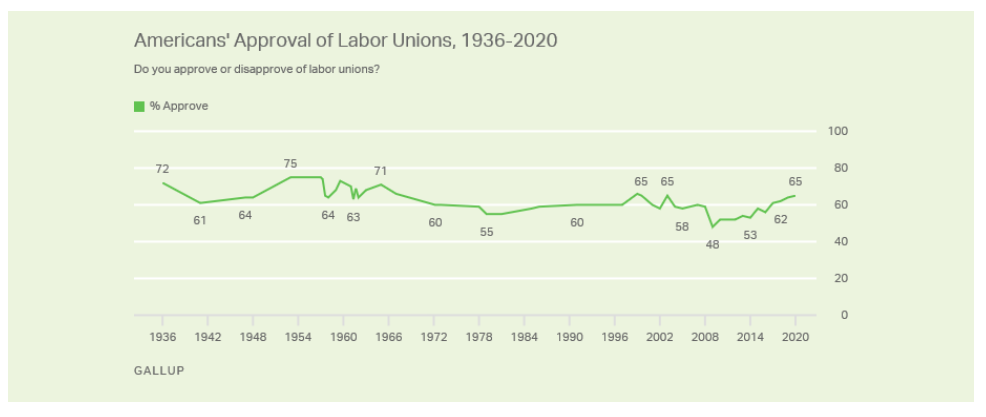

Workers are increasingly coming to understand that they cannot rely on OSHA or the NLRB to defend their interests. Thus, growing numbers of workers are bravely engaging in direct action, risking their jobs, to fight for their rights and the safety of their co-workers. We need to find ways to support them and improve the broader environment for organizing and unionizing. A recent Gallup poll offers one hopeful sign: approval of unions continues to grow.