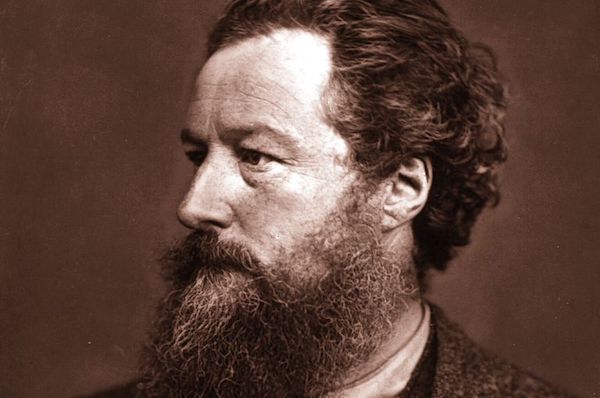

William Morris, who knew a thing or two about furnishings, described the Vendôme Column as ‘a horrid piece of imperial upholstery’, and praised Courbet for his role in pulling it down during the Paris Commune. Despite sustained academic and popular interest in Morris since his death, his views on imperialism and on foreign affairs have generally attracted little mention. On the popular front, his status within the cultural heritage landscape has led him to be easily adapted to a cosy Englishness of patterned tea towels and quirky vintage prints. Scholars of Morris’s politics have more often focused on the place of romanticism in his socialism and on the relationship between socialism, art and labour. Whilst some of Morris’s views on imperialism, and his hatred of national chauvinism, are present in his lectures and in his well-known creative works such as News from Nowhere and The Pilgrims of Hope, never dominant these views can easily be missed. To see the full range of Morris’s anti-imperialism and its importance to Morris’s socialism we have to turn to his journalism, particularly to his articles but also to his regular Commonweal ‘Notes’.

There is no inevitable line from socialism to anti-imperialism, in Morris’s time or since. Many socialists have held pro-imperial views and many still see no contradiction in this. If there is a line in Morris’s case, it probably runs the other way; opposition to British imperial policy was a key factor not just in Morris’s conversion to socialism, but in the shape that his socialism would take. In 1876 Morris became involved in liberal agitation within the Eastern Question Association, campaigning against Disraeli’s foreign policy and against assisting Turkey in its dispute with Russia. Following his Midlothian Campaign Gladstone was returned to office in 1880 and proceeded the following year to issue the Irish Coercion Act and in 1882 ordered the bombardment of Alexandria and further military action in Egypt. These two events signalled to Morris that liberalism and radicalism could on their own go no further, and that politicians, who promise principle in opposition but capitulate when in power, could not be trusted.

Just as socialism doesn’t necessarily lead to anti-imperialism, so the reverse is true. Diverse figures such as the Wilfred Scawen Blunt, Herbert Spencer, and the British Positivists all opposed British imperialism, but none became socialists. To fully account for Morris’s open conversion to socialism in 1883 space would need to be given to his developing ideas on art and society, but, crucially, any account of Morris’s movement to socialism and of his strong anti-parliamentarism needs to factor in his experience with the Liberal party and what he saw as its betrayal of its own principles. On occasion Morris saw a link between these aspects, noting how art students in Britain were learning from examples of Indian art and textiles, while at the same the British were in the process destroying its very source.

At the end of 1884 Morris was part of a group, including Eleanor Marx, Edward Aveling, and Ernest Belfort Bax, that broke away from the Social Democratic Federation led by Henry Mayers Hyndman and formed the Socialist League. Morris took up the position as editor of the League’s journal, Commonweal, which was published monthly until May 1886 when it switched to a weekly. From the outset the League and Commonweal had a clearly internationalist and anti-imperialist stance, with Eleanor Marx using her extensive knowledge and contacts to compile notes on the international movement. It was Bax’s article ‘Imperialism vs. Socialism’ that was the first to appear in Commonweal, following Morris’s editorial introduction and the League’s Manifesto. The manifesto itself noted that ‘all the rivalries of nations have been reduced to this one – a degraded struggle for their share of the spoils of barbarous countries to be used at home for the purpose of increasing the riches of the rich and the poverty of the poor.’

Bax’s article argued that all modern statesmanship was based on the need to find ever more ‘fields for the relief of native surplus capital and merchandise’ and to try and keep other countries from doing the same. He strongly criticised the supporters of British power overseas such as newspapers like the Pall Mall Gazette, and heaped scorn on the idea of a civilising mission that merely provided cover for ‘the vampire Imperialism’. Morris learnt much from Bax’s writing and the two collaborated on several pieces, including their ‘Socialism from the Root Up’ series (revised in 1893 as Socialism: Its Growth and Outcome) which included a seven-part summary of Marx’s Capital.

One of Morris’s own clearest statements came in his article ‘Facing the Worst of It’:

…the one thing for which our thrice accursed civilisation craves, as the stifling man for fresh air, is new markets, fresh countries must be conquered by it which are not manufacturing and are producers of raw material, so that ‘civilised’ manufactures can be forced on them. All wars now waged, under whatever pretences, are really wars for the great prizes in the world-market.

What Morris understood clearly was that new markets are not just found but created, and in the face of resistance they are created with great force and violence. Bax argued that imperialism had the potential to provide new strength and even greater stability for the capitalist system, perhaps delaying its future collapse for as much as another century. Morris feared the same, and it is because he took this possibility seriously that he devoted much of his space in Commonweal to the issue.

Morris was less a detailed and considered theorist than he was a propagandist; his goal, ultimately, was to make socialists. It was therefore necessary not just to convince workers of the truths of socialism, but also to warn them of the dangers of falling prey to nationalist sentiment and to prevent them slipping into a support for an imperialism in which they as workers would not benefit, and which would only entrench their own misery.

Morris’s Commonweal ‘Notes’ are full of attacks on the violence at the heart of imperialism, the hypocrisy used to justify it and on its figureheads. General Gordon, whose death at Khartoum dealt a blow to the popularity of Gladstone, was described by Morris as ‘the general of the Christian commercialists’ and ‘an instrument of oppression whom fate at last thrust aside.’ Henry Morton Stanley, whose exploits in Africa made him a frequent target in Commonweal, was a ‘rifle-and-bible newspaper correspondent’ and Morris suggested he should be put on trial on his return to England, and if not why ‘his hanging men because they refused to serve him at the risk of their lives differs from murder?’

The British Empire was an ‘elaborate machinery of violence and fraud’, and when the Colonial and Indian Exhibition opened in South Kensington in 1886 Morris suggested alternative displays showing the death and horror at the core of British policy. He also took aim at the Poet Laureate, suggesting a ‘pair of crimson plush breeches with my Lord Tennyson’s ‘Ode’ on the opening of the Exhibition, embroidered in gold, on the seat thereof.’ Although comical, it was serious too. Morris had admired much of Tennyson’s work and hated to see a once great artist producing work in the cause of empire.

Yet, while Morris was undoubtedly a staunch socialist and committed anti-imperialist, there are problematic elements to Morris’s thought that need to be dealt with critically too. Though he sincerely believed in the universal brotherhood of labour, he near uniformly presents a dichotomy between ‘civilised’ countries and ‘barbarous’ or ‘semi-civilised’ ones. Morris never travelled outside Europe and, unlike his good friend Wilfred Scawen Blunt, he had no first-hand experience of the people of whom he wrote in his journalism, affording them no level of cultural equality.

His internationalism was therefore limited, mostly euro-centric, and at times he was unclear what internationalism would mean in a socialist future that had overcome the nation as a political entity—if it would have a meaning at all. The end goal for all peoples was something akin to the socialism he saw for Britain, and while he abhorred its practice in his own day he held out the possibility of a socialist colonial policy, thinking ‘it will surely be one of the solemn duties of the society of the future for a community to send out some band of its best and hardiest people to socialise some hitherto neglected spot of earth for the service of man.’

It would be harsh to criticise Morris for failing to give solutions to such seemingly intractable problems. The difficulty of such questions, like the overcoming of the nation state and the question of foreign relations once it was, should not be underestimated. Perhaps, where he can be faulted is for failing to realise that these were actually difficult problems in the first place. At times, he suggests, and this is common across all areas of his socialist thought, that because the class struggle was at the root of society’s problems, once this was overcome then any issues would be easily solved.

Opposition to imperialism needs to be seen as an integral part of Morris’s politics, not only because he himself saw it as such, but also because it is important to remember in our own moment that the British Empire always had internal critics and opponents who knew at the time that injustice, violence and exploitation lay at its core. Since his death, Morris has been claimed by just about all factions of the British left. Clement Attlee once remarked ‘how much more Morris meant to us than Karl Marx.’ To truly do justice his legacy, as more than the artist who believed that ‘fellowship is life, and lack of fellowship is death’, the full Morris must be remembered, full of indignation and fury at the injustice of empire and imperialism.

Peter Halton is a PhD candidate in Intellectual History at the University of Sussex. His research focuses on William Morris, Commonweal, and late nineteenth century British socialism.