Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of the Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Almost every single child on the planet (over 80% of them) had their education disrupted by the pandemic, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural (UNESCO) agency. Though this finding is startling, it was certainly necessary to close schools as the infectious COVID-19 virus tore through society. What has been the impact of that decision on education? In 2017–before the pandemic–at least 840 million people had no access to electricity, which meant that, for many children, online education was impossible. A third of the global population (2.6 billion people) has no access to the internet, which–even if they had electricity–makes online education impossible. If we go deeper, we find that the rates of those who do not have access to the gadgets necessary for online learning–such as computers and smartphones–are even more dire, with two billion people lacking both. To have physical schools closed, therefore, has resulted in hundreds of millions of children around the world missing school for nearly two years.

Macro-data like this is illustrative but misleading. The bulk of those without electricity and internet live in parts of Africa, Asia, and Latin America. For example, before the pandemic, one in five children in sub-Saharan Africa, Western Asia, and Southern Asia had never entered a primary school classroom. One in three girls didn’t have access to education in Northern Africa and Western Asia, compared to one in twenty-five boys. Projections show that one in four children in Southern Asia (population est. 2 billion) and one in five children in Africa (population est. 1.2 billion) and in Western Asia (population est. 300 million) will likely not go to school at all. Studies of the reading levels of children under the age of ten deepen our sense of these inequities: in low and middle-income countries, 53% of children cannot read and understand a simple story by the end of primary school, while in poor countries this number rises to 80% (it is only 9% in high-income countries).

The geographical distribution of low and high-income countries reveals the same old divides. This was the main focus of dossier no. 43 (CoronaShock and Education in Brazil: One and a Half Years Later, August 2021), summarised in our seven theses on the present and future of education in Brazil. These regional and gender inequalities predated the pandemic but have been exacerbated because of the lockdowns.

Signs of improvement are not yet visible. Earlier this year, the World Bank and UNESCO noted that, since the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, two-thirds of developing countries have cut their education budgets. This is catastrophic for large parts of the world where students rely upon public and not private education. Before the pandemic, these gaps were already enormous: in high-income countries, governments spent $8,501 per school-age child, while in poorer countries the amount was only $48 per school-age child. The negative economic effects of the pandemic on developing countries mean that the gaps will widen, with little hope of recovery. As a result, there will be fewer resources to bridge the electricity, digital, and gadget divides, with almost no funds to build lending libraries for smartphones, for example, and much fewer resources to train teachers on how to handle the return of students to the classroom after a two-year hiatus. Since vaccination rates have remained poor in low-income countries, closures will continue indefinitely or risk spreading infections in schools.

Recently, the Indian government released its Annual Status of Education Report 2021, which showed that large numbers of children had no school last year and less than a quarter were able to access online education. As the economic situation for middle-class families worsened during the pandemic, enrolment declined in private schools and increased in public schools. This shift in the wake of dwindling government spending on public education will lead to intensified pressure on students and public school staff, especially teachers.

A study by the Students’ Federation of India (SFI) found that these inequities continue into higher education, with the sharp discovery of a 50% gender gap amongst those who use the internet through their mobile phones in India (21% of women versus 42% of men). In Tribal special focus districts, a mere 3.47% of schools have access to information communication technologies (ICT), according to government data. To make matters worse, the closure of university hostels has hit young women especially hard since living outside the family home served as a refuge from the suffocation of patriarchy in myriad forms, including early marriage and the pressures of reproductive labour.

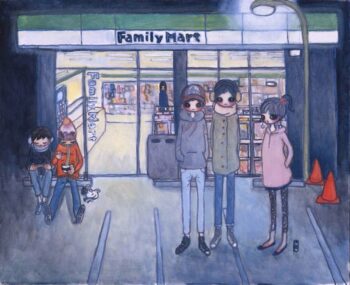

Meanwhile, a bright light shines in Kerala, a state in southern India governed by the Left Democratic Front (LDF) where education rates are 90%. The LDF government has increased education funding in the state and has allowed local self-governments to decide how to spend that money. Before the pandemic, Kerala’s LDF government built high-tech classrooms; once the pandemic set in, it created the necessary infrastructure to allow for online learning. During the pandemic, over 4.5 million students attended school not through smartphones and computers, but through First Bell, a telecast from 8:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. on the government-owned Versatile ICT Enabled Resource for Students (VICTERS) television channel. It is much easier for families to access a television than to access more expensive digital technology. The Kerala example shows the power of centring education around a community’s existing capabilities.

Education is not only about devices and classrooms. It is about how teaching happens and what is taught (a point worth noting during the centenary of the birth of the great educator Paulo Freire, whose legacy we discuss in our dossier no. 34, Paulo Freire and Popular Struggle in South Africa). So many of the successes in Kerala are a consequence of a socialist culture that believes in each child and believes in the importance of elevating rather than denigrating the cultures of the working class and the peasantry.

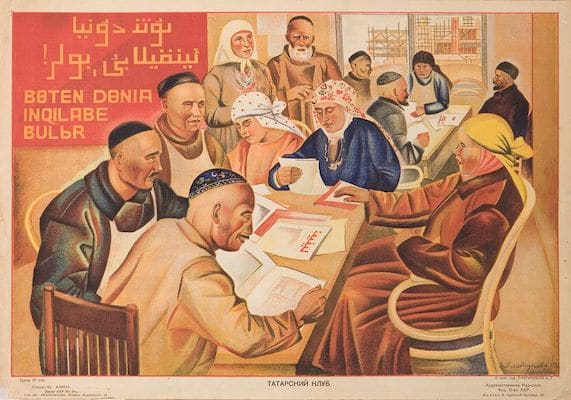

News comes from Brazil that the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) has enabled more than 100,000 people to become literate in the last thirty-seven years. The MST uses Freirean techniques and the Cuban Yo Sí Puedo (‘Yes I Can’) model of education developed by the Latin American and Caribbean Pedagogical Institute (IPLAC). This model emerged after Fidel Castro’s pledge in September 1960 to raise literacy rates to 100%. In eight months, the country realised near total literacy through the Cuban Literacy Campaign. A quarter of a million people, half of them under eighteen, volunteered to go to rural areas and spend nights and weekends improving the skills of the peasantry with chalk and blackboards. They used what Cubans already had in the way of knowledge and enhanced it by teaching them how to read and write, rather than treating them as illiterates needing to be told what to do. Leonela Relys Diaz, one of the original youth volunteers of the literacy campaign, developed the Yo Sí Puedo curriculum in 2000. Now, the programme uses pre-recorded, culturally specific videos alongside highly motivated and trained local facilitators to lift the confidence and skills of people. This programme has also been used in Venezuela since 2003, where it helped teach 1.48 million adults to read and write, thereby eradicating illiteracy in two years.

During the pandemic, socialist projects–such as those of LDF government in Kerala, the Cuban educational programmes, and the MST literacy campaign–are flourishing, while other governments cut their educational funding. ‘It’s always time to learn’, says the MST literacy programme, but this adage is not in use everywhere.

During the pandemic, the University of Nairobi in Kenya decided to shut down its Department of Literature. This department pioneered post-colonial studies when its faculty transformed the colonial English Department, allowing scholars and learners to look deeply into Kenyan arts and culture by absorbing the potential of the African imagination. One of the architects of the new department was the writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who took art to the working-class neighbourhood of Kibera and brought the aesthetic of Kibera to the university. For that, wa Thiong’o was fired and imprisoned in 1978. As word came of the department’s closure, he wrote the poem ‘IMF: International Mitumba Foundation’. Two words of annotation: Mitumba is the Swahili word for ‘second-hand’, used here to poke fun at the International Monetary Fund; the word MaTumbo means ‘stomach’.

IMF: International Mitumba Foundation

First, they gave us their tongues.

We said, it is okay, we can make them ours.

Then they said we must destroy ours first.

And we said it is okay because with theirs we become first.

First to buy their aircrafts and war machines.

First to buy their cars and clothes.

First Buyers of the best they make from our Best.

But when we said we could best them

By making the best from our best

Our own from our own

They said no, you must buy from us

Even though you made the best out of your best.

Now they make us buy the best they have already used

And when we said we could fight back and make our own

They reminded us they know all the secrets of our weapons.

Yes, they make us buy the best they have already used

Second hand, they call it.

In Swahili they are called Mitumba.

Mitumba weapons.

Mitumba cars.

Mitumba clothes.

And now IMF dictates mitumba universities

To produce mitumba intellectuals.

They demand we shut down all departments

That say

We have to stand on our ground,

The best ground from which to reach the stars.But mitumba politicians kneel before IMF,

International Mitumba Foundation,

And cry out

Yes sirs

We the neo-colonial mimics milk the best bakshish.

Mitumba culture creates MaTumbo kubwa

For a few with Mitumba Minds.

Warmly,

Vijay