Back at the height of the pandemic in 2020, I finally managed to beat Dark Souls. It felt a fitting game to play at a time when neoliberalism’s failure to ameliorate crises was becoming particularly acute. Dark Souls presents a faded, dying world presided over by godlike beings whose age of dominion has past but who refuse to relinquish power, sequestering themselves away and forcing countless nameless pawns like your character to unwittingly perpetuate their moribund rule just a little longer. Sound familiar?

But more interesting than Dark Souls’ message was how it was articulated. Rather than written exposition, much of its meaning is conveyed through its use of space. It is a story told in the ruins of crumbling cities and imposing, abandoned palaces and fortresses. It serves as an interesting example of the intersection between the seemingly separate worlds of game design and architecture.

Since the medium’s inception, game developers have drawn influence from architecture for aesthetic and gameplay purposes, sometimes creating lavish facsimiles of real-world buildings. Ubisoft’s Assassin’s Creed series has developed a reputation for painstakingly recreating the likes of Notre Dame, immersing the player in their games’ historical settings. Dark Souls drew inspiration from real-world architecture by having the player scale enormous flying buttresses directly inspired by Milan cathedral.

Some architects too have started paying attention to the world of gaming. The film director and architect Liam Young has argued that cultural mediums such as video games could allow architects to imagine building beyond utility towards a future we actually desire, and many architects already use tools such as the Unreal game engine in their work. Yet as Ernest Adams noted in his column for the Gamasutra (now renamed Game Deverloper) website, there still exist fundamental differences in designing physical structures and in-game spaces. Whereas physical buildings are intended to serve functions such as shelter or organising activity, game spaces are built to facilitate play, such as through exploration or challenging the player’s skill.

How to build a warzone

It would be a mistake to regard in-game spaces as inert containers of play. In Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, philosopher Brian Massumi coined the term ‘field of potential’. In essence, the arena wherein play takes place is not a passive receptacle, but instead actively shapes, informs and directs the nature of play. Therefore, if we want to understand a game’s politics, we need to analyse how it directs the player through its environments.

Modern military shooters, particularly Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2 and its second single-player level Team Player, serve as an interesting case study. The player assumes the role of a U.S. soldier fighting insurgents in a city in Afghanistan, though no explanation is given as to who these insurgents are, why you’re fighting them or even what city you’re in. The only expectation of the player is to move forward and shoot.

This is standard fare for a late ’00s modern military shooter but Team Player warrants analysis in how it articulates its genre’s violent, imperialistic politics through the construction of its city. Aesthetically, it has an element of hostility built into it. Graffiti adorning the walls of houses is mostly written in Arabic (this is an Afghan city, you’ll recall) but the images accompanying them are unambiguous in their meaning, with raised fists and crossed swords. The only English word the player can identify is ‘infidel’, no surprise given the massive cultural implications the word has for western customers. Much of the city is also already ruined by conflict. The schoolhouse where the level concludes is completely abandoned, and its desks and lockers have been repurposed as makeshift barricades.

Furthermore, the level’s layout and progression is remarkably linear. The player is given little room for deviation from the predetermined path, and for a sizeable portion of their level game design renders them unable to move independently. Even when control of the character is regained, they are still expected to follow a predetermined route. Alternative passageways in the ruined school are sealed off by locked doors or rubble and deviating from the desired path is punished with a game over. By restricting the player’s movement and ability to interact with their environment, there are limited opportunities to interrogate its intended message.

Modern military shooters like Call of Duty predicate themselves on their ‘realistic’ representation of contemporary conflict, making the spatial design of Team Player all the more insidious. This city was built with the scars of combat etched into its masonry. It is not a place with history or where communities reside. It is a space where violence is inherent, needing to be ‘civilised’ by the player who is provided the illusion of agency, while being expected to absorb this warped version of Afghanistan down the barrel of a gun.

Interrogation by design

As pernicious as games like Call of Duty are, there are games that use space to articulate a more progressive, even radical, political vision. If Call of Duty can use its field of potential to alienate the player from their environment, others can use theirs to immerse the player within them.

I’m reminded of Infinite Fall’s Night in the Woods. Set in a declining American mining town, Possum Springs, the game features the kind of ‘traditional’ working-class communities that have become an object of fascination with the liberal commentariat on both sides of the Atlantic. Such coverage often has the effect of mystifying such communities behind a haze of half-baked analyses (what will win Labour back the ‘red wall’ etc). By contrast, we see Possum Springs through the eyes of Mae, a college dropout with little to do but wander around her old hometown and jot down her observations with an endearing sardonic wit. Possum Springs is designed to be explored, which in turn enables the game to muse on the plight of deindustrialised communities in a manner more amenable than a New York Times think piece.

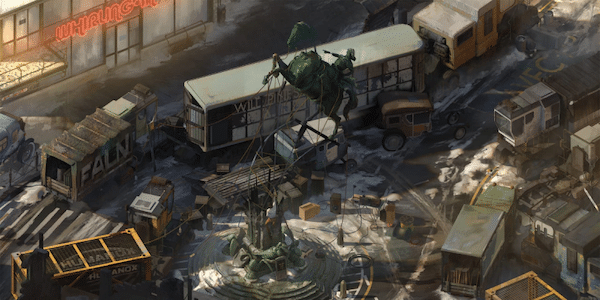

Another refreshing example is Disco Elysium’s setting of Revachol, a city scarred by a failed communist revolution and years of capitalist neglect and repression. The game centres itself on dialogue and exploration, and many of the most memorable interactions occur not with other characters, but aspects of the environment. These include an encounter with a wall scarred by bullet holes from a mass execution decades ago, or the failed hopes that haunt the doomed commercial district. Where Team Player attempts to obfuscate injustice through spatial design, Disco Elysium uses space to actively call attention to it.

As video games continue to evolve, it is inevitable that aspects of their design will bleed into other mediums. And with companies like Roblox and Facebook (sorry, ‘Meta’) looking to make fortunes as platforms for creating and hosting digital spaces, it is imperative that we interrogate the meaning and messages encoded into them. There is power in the way we build our spaces, and that power is no less diminished when they are built from code instead of brick and mortar.

This article first appeared in issue #235, ‘Educate, agitate, organise’.

Gerry Hart is a Red Pepper editor.