The 9th Summit of the Americas, scheduled to take place in Los Angeles in June, remains uncertain. Since the Biden administration has not invited the leaders of Cuba, Nicaragua, and Venezuela on the grounds of “democracy issues”, the leaders of Cuba, Bolivia, Mexico, Argentina, and other countries have expressed the possibility of refusing to participate. Although some countries may eventually go to Los Angeles under pressure from Washington, one cannot help but notice that in Latin America, which has always been regarded as the “backyard of the United States”, the geopolitical winds seem to be changing.

Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador attends a news conference after nearly 92% of voters backed him to stay in office in a recall election with a low turnout, according to results from Mexico’s electoral institute, at the National Palace in Mexico City, Mexico April 11, 2022. REUTERS/Gustavo Graf

More telling than the signs from the Summit of the Americas is the silent emergence of left-wing forces in Latin American countries. Left-wing candidate Gustavo Petro won the largest number of votes (40.32%) in the first round of Colombia’s presidential election, although the situation in the second round on June 19 remains unclear. If both Petro and Brazilian presidential candidate Lula da Silva, who is currently leading in approval ratings, win this year’s elections, the seven most populous countries in Latin America (Brazil, Mexico, Colombia, Argentina, Peru, Venezuela, and Chile, accounting for 80% of the region’s population) will all be governed by left-wing leaders. This would be an important turn in the history of the region.

Since the 15th century, the history of Latin America has been closely linked to colonialism and the slave trade. In the 19th century, U.S. President James Monroe declared the entire Americas to be the sphere of influence of the United States, and since then the U.S. strategy towards Latin America has never changed: complete political and military control of the region along with economic plunder of its natural resources. The U.S. expropriated from Mexico the territories of Texas, California, Nevada, Utah, western Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico; and the Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico remain U.S. colonies to this day. In January, Biden said that Latin America is not “America’s backyard, but its front yard”, which is probably the biggest disagreement among the U.S. political elite about the status of Latin America.

There is an old joke that goes: Why don’t military coups ever happen in Washington D.C.? Because there is no U.S. embassy there. The joke couldn’t be more relevant in Latin America, where Mexico, in 1846, was one of the first victims of the Monroe Doctrine. Since then, the U.S. military has carried out more than 100 interventions, invasions, and coups in Latin America and the Caribbean. In the 1970s, the CIA carried out a series of military coups throughout the region to overthrow left-wing and independent governments. In a secret program known as Operation Condor, the CIA worked closely with military dictators to suppress left-wing activists and prevent the rise of communism among the local populations.

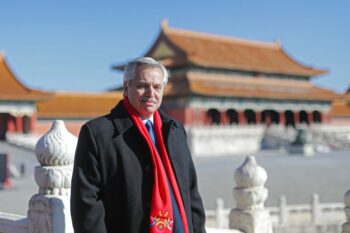

Handout photo released by the Argentinian Presidency of Argentinian President Alberto Fernandez during a visit to the Palace Museum at the Forbidden City in Beijing on February 5, 2022. – fernandez is on official visit in China. (Photo by ESTEBAN COLLAZO / Argentinian Presidency / AFP)

In 1964, a coup d’état supported by the U.S. government in Brazil overthrew President João Goulart of the Labor Party, leading to 20 years of military dictatorship in Brazil. In 1973, Nixon and Kissinger supported Pinochet’s coup in Chile, which resulted in the death of elected President Allende at the presidential palace, the arrest of 38,000 Allende supporters, and the execution of 4,000 others. Subsequently, Chile became a laboratory for neoliberal economics and the “Chicago Boys”, such as Milton Friedman, were brought in to implement comprehensive privatization reforms. In Argentina, Kissinger supported Jorge Videla’s 1976 coup in which 30,000 people were tortured and executed and neo-liberal economics was implemented through his Minister of Economy, Jose Alfredo Martinez de Hoz. Paraguay (1954), Bolivia (1971), and Uruguay (1973), among others, also suffered from U.S.-backed right-wing coups.

In the 1980s, the United States furthered its neoliberal policy by means of the Washington Consensus. As Latin American countries were forced to take on huge debts in the 1970s and into the 1980s, the Washington Consensus, through the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, set policies to drastically cut public benefits, privatize state-owned enterprises, deregulate business and capital markets, and fully liberalize finance and trade. As a result of neoliberal reforms and the Washington Consensus, 50 million people in Latin America fell into poverty from 1970 to 1995, and the poverty rate grew from 35% (1970) to 45% (2001). During this period, external debt tripled from $67.31 billion (1975) to $208.76 (1980), 60% of which was public debt. The debt-to-GDP ratio jumped from 3% (1970) to 8.5% (1989), further stifling the possibility of economic development. The effects of holistic privatization and the destruction of the industrial structure continue to this day as these countries struggle to escape the position of underdevelopment and indebtedness in which they were placed.

In fact, back in 1985, few state leaders could clearly understand, let alone question, the debt traps that most Third World countries were forced into. Former Cuban President Fidel Castro had called for a debt moratorium because it was morally irrational and mathematically impossible to pay off these debts. His comments generated widespread interest in international public opinion. In contrast, today’s leaders in Washington are actively advocating a new Marshall Plan for Latin America, which would mean more increases in its debt. As Vijay Prashad denounced at COP26 in Glasgow, imperialist powers plundered their colonies of the wealth that then returned to developing countries in the form of loans. The Latin American countries produce to pay off their debts, and in turn sign more debt contracts with the very countries that have plundered wealth from the colonized countries. This is the debt trap: the economy and politics of these countries prioritize serving debt repayment over their own economic and social development, and the lack of development leads to more debt.

In 1999, a progressive wave began in Latin America with the election of Hugo Chavez as President of Venezuela. This reflected the discontent of the Latin American people with neoliberalism and U.S. hegemony. In less than a decade, progressive and left-wing parties in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Paraguay won elections consecutively. For the first time in Latin American history, a group of popular regimes came to power through democratic elections. Chavez advocated the “Bolivarian Revolution”, created the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA), and initiated the process of deep integration in Latin America. Subsequently, several regional multilateral organizations, such as the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), were established, and Brazil helped to bring about the BRICS Summit.

The U.S. response to this progressive wave started a period of counterrevolution marked by economic sanctions, instigated coups, and hybrid wars. The new round of U.S. intervention brought setbacks to popular regimes and progressive parties in Latin America. In 2012, Paraguayan President Fernando Lugo was impeached in a “constitutional coup” and in 2013, the CIA fomented violent street protests in Venezuela and was suspected of being involved in the mysterious death of Chavez. In 2016, Brazil’s President Rousseff was subverted by a legal persecution, and former President Lula, who belonged to the same labor party, was unable to run for office due to corruption charges (which were later proven to be utterly fabricated). In 2019, the U.S.-led Organization of American States (OAS) claimed the Bolivian election was fraudulent; this was followed by a coup d’état that led to the resignation of President Morales.

The U.S. has used different hybrid war tactics according to the different situations of Latin American countries. In the case of Venezuela, a regional leader in progressive thinking, the tactics are simple and brutal: prolonged economic sanctions to keep worsening its economy, exclusion of the country from the SWIFT system to prevent it from conducting normal international trade, and outright freezing and seizing of the country’s gold and foreign exchange reserves. These tactics are much the same as those imposed on Russia today.

And for Brazil, Latin America’s largest economy and a key player in geopolitics, the United States employs a more comprehensive hybrid war strategy that included the impeachment of former President Rousseff. Former President Lula also suffered judicial persecution, having been arrested and imprisoned for nearly two years on suspicion of embezzlement; the judge in charge of the case, Sergio Moro, was later appointed Minister of Justice in the Bolsonaro administration. The case went through the entire judicial process until Brazil’s Supreme Court found Lula not guilty of any crime.

In Argentina, the neoliberal government of former President Mauricio Macri left the country with tens of billions of dollars of IMF loans, and the country remains in a debt trap to this day. Similar to the situation in Brazil, judicial persecution of left-wing and progressive leaders escalated after Macri’s ascension to the presidency. Former President Cristina Kirchner was accused of more than a dozen crimes; some of her ministers and collaborators were charged with corruption, illegal association, and other crimes; and even former Vice President Amado Boudou was “preventively” imprisoned. All of these people were victims of U.S.-sponsored lawfare, and all were acquitted by their own judicial systems years later.

A second wave of popular governance is currently building in Latin America. It began with the election of López Obrador as president of Mexico in 2018. He has pushed for social reforms and recently nationalized Mexico’s lithium industry, elevating lithium to a strategic mineral and declaring its exploration, extraction, and use to be the exclusive right of the state. In 2019, the Frente de Todos (Popular Front), a coalition of left-wing, Kirchnerist, and Peronist parties, won elections in Argentina, with Alberto Fernández and Cristina Kirchner elected president and vice president, respectively. In 2020, the Movement Toward Socialism (MAS) returned to power in Bolivia with a new president, Luis Arce, who had served as economy minister in the Morales government. In 2021, Pedro Castillo in Peru and Gabriel Boric in Chile won presidential elections in their respective countries. Also last year, Xiomara Castro, the female representative of the left-wing party Liberty and Refoundation, was elected President of Honduras.

Unlike the wave of progressivism and left-wing governments two decades ago, today’s global geopolitical environment is undergoing a quiet and dramatic change. The U.S. empire is declining from its pinnacle. Although the U.S. military had to withdraw from Afghanistan, the U.S. political elite still arrogantly believes that the empire can contain both Russia and China, intervene in a proxy war in Ukraine, provoke China with Taiwan, and ratchet up sanctions against Russia and tensions with China, while still maintaining “order in the yard” on the American continent.

Unlike the wave of progressivism and left-wing governments two decades ago, today’s global geopolitical environment is undergoing a quiet and dramatic change. The U.S. empire is declining from its pinnacle. Although the U.S. military had to withdraw from Afghanistan, the U.S. political elite still arrogantly believes that the empire can contain both Russia and China, intervene in a proxy war in Ukraine, provoke China with Taiwan, and ratchet up sanctions against Russia and tensions with China, while still maintaining “order in the yard” on the American continent.

At the same time, China’s influence on Latin America in terms of investment, trade, and regional cooperation is rapidly increasing. The BRICS summits, which began in 2008, the China-CELAC Forum, which began in 2014, and the Belt and Road Initiative, which has attracted widespread interest, are all demonstrating China’s growing influence in Latin America. Unlike the progressive waves of the past, Latin American people can now expect a stronger China. Today’s China advocates multilateralism and a new type of international relations based on mutual respect, fairness and justice, and win-win cooperation, rather than war or intervention. It is also an opportunity for governments that aim to catch up with developed countries in terms of economic development and technology, because China is now the second largest economy after the United States and is expected to become the largest one by 2028.

While the left in Latin America is on the rise, that does not mean victory is within reach. The economic and political realities facing today’s elected progressive governments are far worse than they were in 1999 when the first wave of popular parties rose to power. The task before these governments is awe-inspiring. At the same time, Washington is acutely aware that destabilizing Cuba and Venezuela is key to destabilizing the rest of the Latin American continent, and they will continue to use hybrid wars and lawfare to try to subvert both countries.

The White House and the State Department are concerned about the situation created by the crisis of the Summit of the Americas. This is not the first time that Latin American countries have complained about the U.S. exclusion of Cuba, but in the context of the rise of the left across the continent, such complaints are now eroding U.S. influence in Latin America while pushing left-wing leaders to take more radical positions. So, we can definitely expect to witness an aggressive U.S. media offensive against Cuba and López Obrador – the same Mexican president who has driven the debate on whether Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua should participate in the summit.

Pressured by the United States, Latin American heads of state may still end up attending the Summit of the Americas in Los Angeles. Colombia’s right-wing could still form a coalition to defeat Petro in a runoff vote. Even Lula could still be backstabbed by the U.S.-led hybrid war and lose the Brazilian presidential election. After all, the past 12 months have seen U.S. National Security Adviser Jack Sullivan, Deputy Secretary of State Victoria Newland, and CIA Director William Burns all express concern about the Brazilian election – an election that, in the discourse of the U.S. political elite, will be “the most critical one since the restoration of ‘democracy’ [in Brazil] in the 1980s”.

The rejection of imperialism by the progressive left-wing movements in Latin America suggests the goal of an independent path, and the strengthening voices of the working classes against neoliberalism. But the construction of socialism takes time and international cooperation. Thus, the struggles of the political parties and movements representing the people after winning elections are not only about the development of their own countries, but also about the defeat of U.S. intervention. Looking ahead, Latin America will not sail smoothly towards socialism, but will endure a tortuous process. In this process, China has a key role to play in supporting these countries on the path to full independence by promoting peace, multilateralism, and friendship among the people across the world.