SYDNEY and KUALA LUMPUR, Sep 13 2022 (IPS)—After a quarter century of economic stagnation, African economic recovery early in the 21st century was under great pressure even before the pandemic, due to new trade arrangements, falling commodity prices and severe environmental stress.

European scramble for Africa

Africa’s borders were drawn up by European powers, especially following their ‘Scramble for Africa’ from 1881 ending by World War One. Various culturally, linguistically and religiously different ‘ethnic’ groups were forced together into colonies, to later become post-colonial ‘nations’.

Europeans came to Africa seeking slaves and minerals, later building colonial empires. The U.S. attended the 1884 Berlin Congress, dividing Africa among European powers. Colony-less ‘latecomer’ Germany got Southwest Africa and Tanganyika, now Namibia and mainland Tanzania respectively.

Namibia’s Herero and Nama peoples revolted unsuccessfully against German occupation in 1904. General Lothar von Trotha then ordered “every Herero … shot”. Four-fifths of the Herero and half the Nama died!

Communities were surrounded, with many killed. Others were held, with many dying in concentration camps, or driven into the desert to die of starvation. In 1984, the UN Whitaker Report concluded the atrocities were among the worst 20th century genocides.

Asymmetric interdependence?

Europe’s post-Second World War recovery benefited immensely from their primary commodity exporting colonies. After the wartime devastation, European imperial powers relied on colonial currency arrangements for precious foreign exchange.

Imperial power also ensured captive colonial markets for uncompetitive post-war European manufactures. Recovery and competition brought down commodity prices, especially after the Korean War boom. For well over a century, such prices have declined against those for manufactures.

As decolonization became inevitable, French politicians promoted the notion of ‘Eurafrica’, mimicking the U.S. Monroe Doctrine’s claim to Latin America. French elite discourse insisted African independence should be defined by (asymmetric) ‘interdependence’, not ‘sovereignty’.

Although Germany lost its few colonies in Africa after losing the First World War, the influential West German Die Welt wondered wistfully in 1960, “Is Africa getting away from Europe?”

From decolonization to Cold War

The U.S. was the first nation to recognize Belgian King Leopold II’s personal claim to the Congo River basin in 1884. When Leopold’s brutal atrocities and exploitation of his private Congo Free State domain, killing millions, could no longer be denied, other European powers forced Belgium to directly colonize the country!

Since then, the U.S. has shaped the Congo’s destiny. The U.S. has been keenly interested in its massive mineral resources. Congolese uranium, the richest in the world, was used in the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombs. But Washington would not allow Africans control of their own strategic materials.

Patrice Lumumba became the first elected prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). An advocate of pan-African economic independence, his wish for genuine independence and sovereign control of DRC resources threatened powerful interests.

Lumumba was brutally humiliated, tortured and murdered in January 1961. The shameful assassination involved both U.S. and Belgian governments which collaborated with Lumumba’s Congolese rivals.

Struggling to stand up

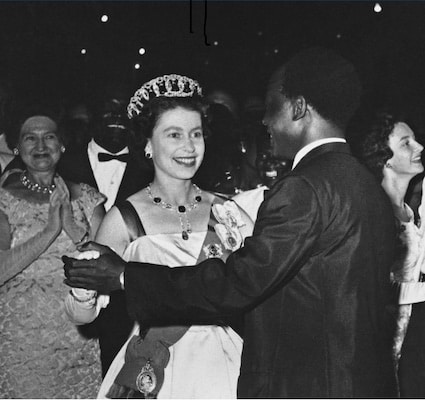

Pan-Africanist leader Kwame Nkrumah wanted independent Ghana to chart an ‘anti-imperialist’ path, staying non-aligned in the Cold War. He wanted hydroelectric dams to power Ghana’s industrial progress, beginning by smelting its bauxite to develop an aluminium value chain.

The U.S., UK and World Bank agreed to finance the Akosombo Dam, on condition it provided cheap energy to a Kaiser Aluminium subsidiary to process alumina for export to Kaiser. This arrangement was only rescinded decades later, early this century.

Ghana made technical cooperation agreements with the Czechs and Soviets to build two otherdams. But both were ended after Nkrumah was overthrown in a military coup abetted by Washington in February 1966. Thus, Nkrumah’s development ambitions for Ghana were killed.

A scaled-down Bui dam was finally built by Chinese contractors decades later. Nkrumah’s 1965 book, Neo-colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism, was probably the final straw in embarrassing the West.

Elsewhere, Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa ‘African socialism’ focused on developing villages and food security. Western antagonism ensured Ujamaa’s failure, while his efforts were harshly condemned to deter other Africans from trying to chart their own paths.

Meanwhile, Nyerere’s pro-Western contemporaries were supported by the West. Such countries, e.g., neighbouring Kenya and Uganda, received much more Western aid although their development records have not been much better.

A luta continua

At independence, Zambia had no universities, with only 0.5% completing primary education. The country’s copper mines were mostly in British hands. Most people survived on limited land for the villagers, without electricity and other amenities.

Hemmed in by Western-supported racist states, President Kenneth Kaunda—a devout Christian—sought foreign help to bypass hostile South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to change the landlocked nation’s fate.

After the U.S. and World Bank refused to help, he reached out to the Soviet bloc and China.China built a $500 million railway linking Zambia to the Indian Ocean through Tanzania.

Côte d’Ivoire has long been a major producer of cocoa and coffee. But three decades of misrule by its pro-Western founding father, Felix Houphouet-Boigny, ensured endemic poverty and stark inequalities, culminating in civil war.

In 2020, almost 40% of its people lived in ‘extreme poverty’. In 2019, the middle-income country’s human development index score was a low 0.538, which dropped to 0.346, when adjusted for inequality.

Both Kaunda and Houphouet-Boigny later abandoned their early, more neo-colonial policies. Zambia nationalized copper mines, hoping to improve living conditions, instead of enriching foreign investors.

Meanwhile, Ivorian cocoa was withheld to secure better prices. But both efforts failed, as copper and cocoa prices collapsed. Thus, both nations were severely punished for trying to better their fates.

Non-alignment best

During the first Cold War, Western hostility to African aspirations forced many to turn to the ‘socialist camp’ to build infrastructure and develop human resources. Washington then was as concerned with economic gain as countering ‘Reds’.

The Kennedy administration had increased foreign aid, urging allies to do likewise. But instead of supporting African aspirations, the West pursued its own economic interests while claiming to support post-colonial aspirations.

Increasing African government indebtedness over the 1970s forced many to accept structural adjustment programme policy conditions imposed by international financial institutions from the 1980s. Of course, developing countries following International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank prescriptions became Western darlings.

Nyerere observed:

The IMF … makes conditions and says, ‘if you follow these examples, your economy will improve’. But where are the examples of economies booming in the Third World because they accepted the conditions of the IMF?

Cold War considerations have also meant U.S. interest in Africa has waxed and waned. Now, the West warns of imminent Chinese ‘take-overs’ and nefarious Russian designs. China seems more interested in financing and building infrastructure, while Putin promotes Russian exports.

Neglected by the U.S. after the first Cold War until its 21st century African initiatives, including Africom, African nations have increasingly welcomed alternatives to the West, albeit somewhat warily.

Together, the world can help Africa progress. But if support for the long cruelly exploited continent remains hostage to new Cold War considerations, Africans will choose accordingly. Non-alignment is now the pan-African choice.