Among the many crises hitting low and middle income countries (LMICs) today, the emergence of extreme hunger and undernutrition is getting much less attention than it should. The cost-of-living” crisis in advanced economies gets a lot of international media attention. It is certainly evident and has political implications.

But what is occurring in much of the rest of the world is even more severe and potentially life-threatening: the inability of significant proportions of the population in low and middle income countries to access the food necessary for healthy survival. And while some of it is the result of global and local supply shortages (including not just the Ukraine war but the impacts of climate change affecting agriculture), the more important factors are the market forces of concentration and speculation, of globally determined macroeconomic processes, and the collapse of livelihood opportunities affecting these countries in the post-Covid world.

It is important to note that even before the latest onslaught of global food and fuel price increases catalysed by the Ukraine war, a large part of the world could not afford the minimal nutritious diet as described by the FAO. These show that in most of Sub-Saharan Africa more than 80-90 per cent of the population could not afford the basic nutritious diet, while in India the proportion was above 70 per cent and in Pakistan above 80 per cent.

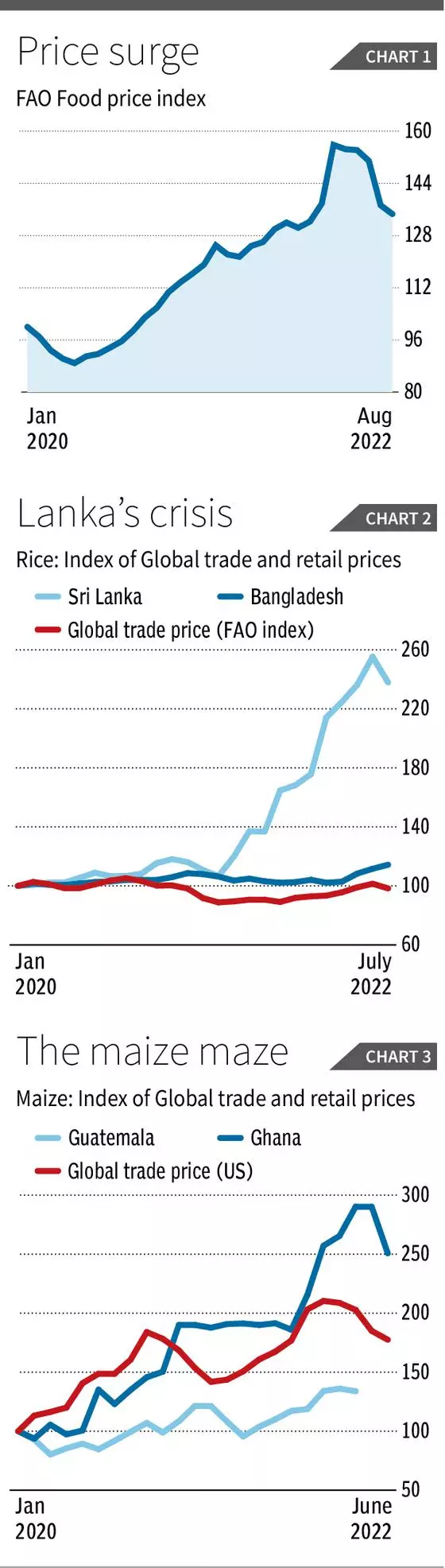

Since then, we must assume the situation has deteriorated dramatically, if only because of the significant increase in global food prices since early 2021, which has not been matched by similar increases in the nominal wages of most workers or the incomes earned by self-employed people in these countries. Chart 1 shows that the FAO’s food price index (which covers wholesale and trade prices rather than retail prices) increased more than 40 per cent between January 2021 and March 2022.

Much is currently being made of the subsequent decline in that index, by around 16 per cent up to August 2022–but the food price index still remains more than one-third higher than its level at the start of 2020.

We have previously argued (Macroscan June 2022) that the aggregate global supply and demand did not change much even with the Ukraine war, and that other factors were more important in driving up and then generating volatility in world markets.

Speculative spurt

Two major factors were profiteering by major grain trading agribusinesses, which experienced dramatic increases in profitability in January-March 2022; and financial speculation in wheat futures markets, which also impacted spot markets.

We noted the big increase in speculative activity in grain futures markets especially in March-April. For example, in the Paris wheat market, financial investors increased their open positions from a 23 per cent share in May 2018 to 72 per cent share in May 2022. As a result, just as during the 2007-09 global food crisis, prices shot up and then came down again in commodity futures markets.

But this decline is cold comfort to low and middle income countries, which continue to face higher prices because of currency depreciation that has affected import prices and price ratchet effects in domestic markets.

Consider some of the retail price increases in countries that are otherwise facing economic problems (if not absolute external debt crises) of various kinds. Charts 2 and 3 provide data on world trade prices of rice and maize (in index terms, with July 2020=100), along with the retail prices in some countries that import these grains.

From Figure 3 we can see that the price indices of global and local prices of rice in Bangladesh and Sri Lanka remained broadly the same and did not increase until January 2021. Thereafter, global rice prices did not increase, but not by very much. And they went down again from June 2021.

By contrast, rice prices in Bangladesh went up faster and stayed higher than global prices from June 2021 onwards, such that in July 2022, they were 14 per cent higher than in January 2020. Remember that rice is the most important staple grain in Bangladesh, and that the nominal wage index has been stagnant for more than a year. This translates into a truly significant real increase in a dominantly poor population.

The case of Sri Lanka is even more striking, perhaps unsurprising given the very severe crisis in that country especially in the past year. Retail rice prices have more than doubled since early 2021, in a country with falling wages and rising unemployment, adding to the sharp increase in hunger that has been a major outcome of the broader crisis.

Falling currencies

In both these countries, currency depreciation has been an important factor, since global commodity prices are typically priced in U.S. dollars. The Bangladeshi rupee has fallen by more than 20 per cent relative to the U.S. dollar between January 2020 and September 2022, while the Sri Lankan rupee has gone down by more than 48 per cent till July. The significance of currency movements becomes more evident when looking at maize prices. Both Ghana and Guatemala are maize importers (and facing serious economic problems and growing hunger concerns).

Yet the retail price of maize in Ghana has increased much more sharply than the world trade price, and stayed higher even in periods when the global price fell. The Ghanaian cedi declined by more than 33 per cent relative to the U.S. dollar over this period.

However, in Guatemala, where there was no depreciation of the currency in terms of the U.S. dollar, the maize price has increased but remained below the global price change.

This brings out clearly how so many developing countries are caught in a web that is only partly of their own making, and strongly affected by the neo-liberal policies that they were all encouraged to adopt. This made many poor countries net food importers without strong options in period of sudden global rice increases.

The low interest rates in the advanced economies ever since the Global Financial Crisis encouraged much more borrowing all over the world, with “cheap” money created in the North also flowing increasingly to “emerging” and “frontier” markets, especially in the form of new debt against bond issues.

Many LMICs were encouraged to liberalise rules and experienced significant increases in external borrowing by both public and private agents, and opened up their capital accounts with the false promise of attracting foreign capital that would be used for productive investment. Such strategies were actively encouraged and even cheered on by the IFIs and the Davos crowd.

But LMICs were more battered by the Covid-19 pandemic and results of the Ukraine war, had weaker recoveries because of lower fiscal response, and were heavily beholden to short-term capital. Increasing interest rates in U.S. and EU resulted in a “flight to safety” with self-fulfilling effects on balance of payments and currencies. This was a tragedy foretold, resulting from internal and external financial liberalization.

Failure of IFIs and G7 to provide speedy and effective debt relief has only worsened the problem. Now stagflation is not just a possible danger but an ongoing process. And it is having especially tragic results in terms of significant increases in hunger.