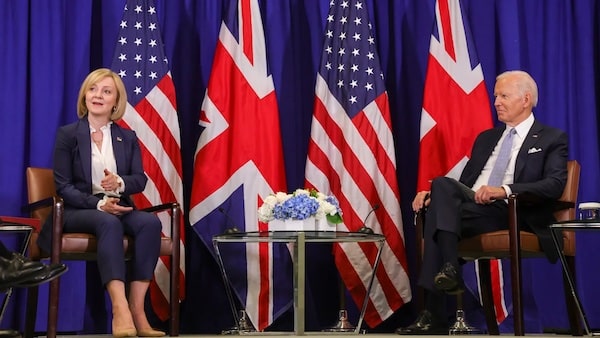

Liz Truss, the UK’s new prime minister, must be in the running for the most anti-China British leader in a century.

Truss has done more than any other single politician to move the Conservative Party, and therefore the British government, from wanting to be a close friend of China, during the David Cameron premiership, to today where the UK is openly threatening Beijing’s economic stability and political security.

As foreign secretary in 2021, Truss convinced fellow G7 foreign ministers to include a line in their closing communique condemning China’s economic policy. Then, in a major speech this April, she threatened to crack down on China’s rise if they “don’t play by the rules”.

As she vied for the top seat in 10 Downing Street this August, Truss pledged that, if she were made prime minister, she would officially designate China a “threat” to British national security.

When the speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, visited Taiwan that same month, in a deeply provocative trip aimed at angering China, Truss openly talked about the need for the West to support the Taiwanese separatist movement.

Britain’s Conservatives compete to be the most belligerent against Beijing

To see the significant influence that anti-China hawks now have in the UK’s domestic politics, we need look no further than the Conservative Party leadership contest, where candidates competed to see who could be the most aggressive against Beijing.

Truss’ major opponent in the race was the former chancellor of the Exchequer, Rishi Sunak. As chancellor, Sunak had emphasised closer economic ties with China. But it seems he feared appearing “soft” before the Conservative Party membership, and so in July, he came out as an anti-China hawk, claiming Beijing was Britain’s “number one threat”.

Sunak was not alone. Penny Mordaunt, in an ultimately unsuccessful bid to remain in the Conservative party leadership race this summer, criticized Boris Johnson for having a supposed soft touch on China. She argued Johnson had prioritized the economy over national security.

Tom Tugendhat, another failed Conservative leadership contender, who served as chair of the Foreign Affairs Select Committee and was Truss’ pick for minister of security, warned in an interview that China allegedly poses a great danger to the British people.

NATO’s new cold war on China

The UK’s Conservative leadership race came on the heels of a NATO summit in Madrid in June, where the Western military alliance declared China to be a “strategic competitor” that poses a “systemic challenge” to “our interests, security and values.”

Britain’s shift toward hard-line anti-China policies also coincides with the same move in the United States, where the Joe Biden administration has continued Donald Trump’s campaign to counter China’s influence across the globe.

After decades of relatively stable co-operation and co-existence, Western leaders are now falling over themselves to attack China.

Yet these claims of Chinese aggression toward Europe have no real basis. In its thousands of years of history, China’s armies have never set foot on European soil, never mind marched victorious into a European capital.

The Chinese state has never colonized European cities. Looted European art does not sit in Chinese museums. Chinese people have never demanded exemption from European law, nor inserted themselves into European politics. Chinese businesses have never used the threat of Chinese naval fleets to open European markets on favourable conditions.

Certainly, China has become more assertive on the world stage in the era after the 2008 financial crash. As Beijing-based journalist Michael Schuman lays out in his book “Superpower Interrupted”, for many in China, the late 19th and 20th centuries were a period of aberration, a time when one of the world’s natural great powers was forced by colonialism, war, and internal crisis into a diminutive role.

Economic expansion since the 1980s, and the sense of perpetual crisis in the West, has allowed the Chinese leadership to reassert Beijing’s place as a potential superpower.

Yet the Western media always takes the least charitable view of any move made by Chinese leadership. Every time a Chinese fund invests in Africa, or a Chinese ship enters the South China Sea, or the Chinese government signs a security agreement with another country, Western media outlets will warn, Cassandra-like, of the impending doom of Chinese global domination.

China’s newfound assertiveness must be put in its proper geopolitical context.

For decades, the Western alliance has been at war continuously. In this same period, China hasn’t dropped a single bomb on a single person.

China has just one foreign military base, in Djibouti, which is part of international anti-piracy operations. (Western governments allege that China is building another secret base in Cambodia. It is not clear if this is true, but even if it is, that means Beijing has a mere two foreign military bases.)

The United States, on the other hand, has some 800 foreign military bases in more than 70 countries.

Even the United Kingdom, a country with a total population smaller than the membership of the Communist Party of China, dwarves Beijing in foreign base totals.

China is not involved in regime-change operations. And unlike the United States, it does not seek to assassinate foreign leaders.

While several countries on China’s borders suffer under stifling economic sanctions, which bring death and misery to untold numbers, none of these sanctions were initiated by China.

Judged by any metric, China is by far the least aggressive of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, and is the only member not currently involved in a war.

China poses no threat to the West

Given these historical and contemporary geopolitical realities, there is no basis for anyone in the US or Europe to consider China a national security threat.

The United Kingdom and Europe as a whole face manifold issues, from the effects of climate change, to the energy crisis, to entrenched inequality, to an ongoing public health crisis. None of these can rightly be blamed on China building bridges in Africa or developing security arrangements in the Pacific.

What truly motivates British political leaders to feel this way can be gleaned from passing comments made by figures like Tom Tugendhat, one of the candidates in the Conservative leadership contest.

Tugendhat was the long-time chair of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, and the co-founder of the China Research Group (CRG), a self-appointed Beijing watchdog.

In response to a question by Quartz about why he saw the rise of China as such a threat, Tugendhat responded:

The UK, by accident of history, was fundamental to the writing of the operating system of the global system from 1700 through to 1990, and the UK economy, more than almost any other, was built on the basis of it…

We therefore have a choice, which is, do we defend the system upon which our prosperity is built?

In other words, the UK’s economic prosperity still rests on the system that came out of the colonial period, and China represents a credible challenge to that colonial legacy.

The “threat” felt in Western capitals, then, is not of Chinese gunboats on the Thames, but of something much less tangible. The return of China to superpower status is not a threat so much for what Beijing will or will not do, but of what this represents for Western hegemony.

As Tugendhat put it, since the 19th century, the West – and particularly the UK and the USA – have used their status as the pre-eminent imperial powers to write a rule book of their own design.

This is often euphemistically called the “rules-based international order”, but amounts to nothing more that the fruits of centuries of colonialism.

China, with its 1.4 billion population, huge economy, and strong state, is the first credible challenge to that Western colonial framework since the end of the first cold war.

Indeed, given China’s integration into the global economy, and the parallel rise of other nations in the Global South, this may be the greatest challenge to the colonial order since the Age of Victoria.

The fear among Western policy-makers is real, but the concern is not that Europe will be dominated by China; instead, it is a fear that China’s rise means the end of European domination.

After all, the long, bloody, and exploitative history of European involvement in Asia, Africa, and much of the Americas gives the people of the Global South little reason to remain loyal to their old colonial masters, even if they try to forcibly return the gunboats to port.