Part IV: Declaration of World War

Now, as in the worldwide revolutionary upsurge of the 1960s-70s, the strongest emotive and analytical connections between China’s historical experience and the Palestinian resistance come through the memory of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Far fewer, in either China or (especially) the West, are likely aware of the contributions made by Japan itself – or rather, a small but impactful minority of Japanese people – in cementing that affective bond in the consciousness of the global left.

Throughout the 1960s Japan was wracked by massive revolutionary upheavals seeking to end its subordination to the United States, which had rehabilitated and largely reinstalled the WWII-era fascist leadership and converted the country into a massive rear base for imperialist aggression against Korea, Vietnam, and China. From these struggles emerged a plethora of armed New Left formations, some of which (most infamously the United Red Army) sadly consumed themselves in fratricidal violence. Seeking a literal way out of these internecine battles, the Japanese Red Army (JRA) was founded in 1971 on a doctrine that sought to expand the armed struggle from its domestic fetters and into the heartlands of world revolution.

As originally formulated by the JRA’s founding chairman Takaya Shiomi, this “international base theory” would have relocated their operations to secure bases in established socialist states, predominantly in the Eastern Bloc. Fellow Red Army leader Fusako Shigenobu soon amended this proposal, arguing that “battlefields of the struggle in transition to liberation and revolution should be our international bases.” Foremost among these active revolutionary battlegrounds in her analysis was Palestine; under her leadership the JRA relocated shortly after its founding to the refugee camps in Lebanon and cemented a close military alliance with the PFLP.

It was just a year later, in May 1972, that the JRA exploded into the popular consciousness and cemented its reputation – for heroism throughout much of the Arab world, and for “terrorism” in the West – by mounting an attack at Lod Airport in Tel Aviv. The operation led to 26 deaths; in an early precursor to the narrative battle surrounding October 7, official accounts paint it as a cold-blooded massacre, while the JRA and other eyewitnesses insist the attackers had a clear military objective (the airport control tower) and most victims were killed in the crossfire. In any case, Zhang Sheng notes that by striking so deep within occupied Palestine the JRA had scored what “was regarded by some as the first victory against Israel, which crippled the myth of Israel’s invulnerability.” The propaganda value of the operation was certainly not lost on Israeli leaders, who months later assassinated PFLP spokesman Ghassan Kanafani and his niece in direct retaliation.

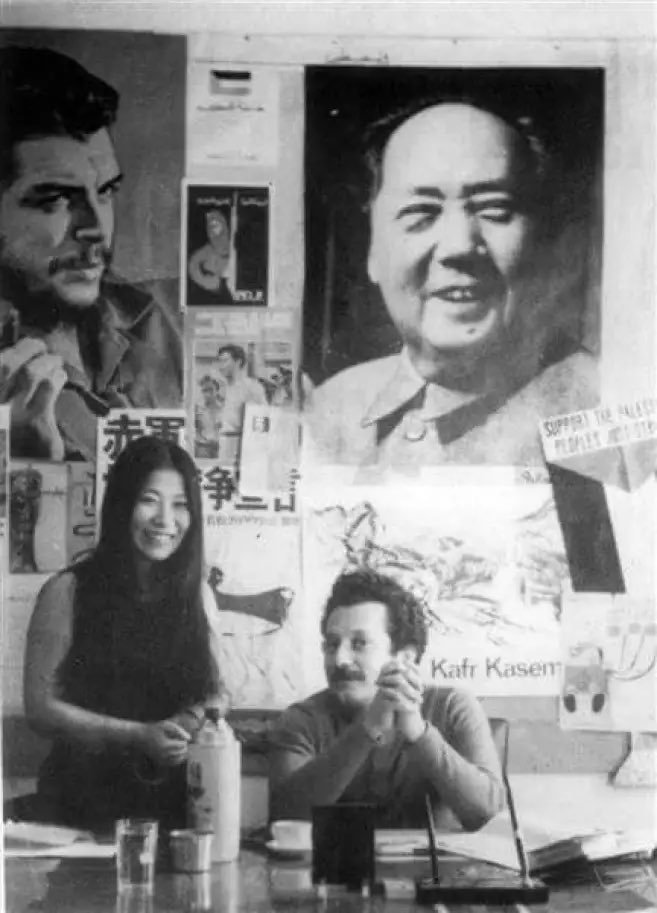

Fusako Shigenobu (L) and Ghassan Kanafani (R) at the office of al-Hadaf magazine in Lebanon, 1972. Behind them are portraits of Che Guevara and Mao Zedong as well as a poster for Sekigun-PFLP.

The JRA’s first year of operations also produced an enduring piece of militant documentary filmmaking, Red Army-PFLP: Declaration of World War (Sekigun-PFLP: Sekai senso sengen, or 赤軍PFLP・世界戦争宣言). Co-directed by Masao Adachi – who subsequently took a three-decade hiatus from cinema to join the JRA in Lebanon, eventually returning to direct a dramatization of the Lod Airport operation and more recently a biopic of Shinzo Abe’s assassin – it features extensive interview footage with Shigenobu, Kanafani, and iconic PFLP fighter Leila Khaled. In one such interview Khaled relays a global appeal from the JRA-PFLP alliance: “Japanese comrades, and revolutionary comrades in China, Vietnam, and the rest of the world, let us posit the following slogan and persist in fighting for its realization: ‘Anti-imperialist revolutionary forces of the world, unite!’”

Elsewhere the film repeatedly alludes to revolutionary China’s centrality as a source of theoretical inspiration and an active participant in the struggle. One JRA narrator proclaims that “the ‘Anti-Imperialist/Anti-Zionist/Third World War’ that our PFLP brothers propose and practice, and the ‘Anti-America/Anti-Japan War’ of our Chinese brothers, are, in our own words, one and the same with what we propose and practice as the ‘World Revolutionary War.’” Another scene shows PFLP guerrillas studying an Arabic edition of Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong (the “Little Red Book”), while a moving five-minute musical interlude is set to all three verses of the “Internationale” in Chinese.

Over its three decades of existence, the Japanese Red Army had few if any direct equivalents (especially outside the Arab world) as an organized co-belligerent and de facto foreign brigade of the Palestinian armed resistance. Lillian Craig Harris’ 1977 article does include an intriguing note to the effect that: “In November 1971 Fatah said that an undisclosed number of Chinese youths had volunteered to join the Palestinian guerrilla organizations through an offer made to the PLO office in Peking. However, Fatah did not say if it had accepted this offer and no Chinese ever appeared in Palestinian fighting units.” But the JRA’s dedication to the cause did find a spiritual echo, and a direct homage, in the extraordinary life story of Zhang Chengzhi: the first Red Guard of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

Zhang was born in Beijing in 1948, to ethnic Hui Muslim parents who nonetheless gave him a secular revolutionary upbringing. Later in life he would attach deep significance to the fact of his birth just months after the Nakba, lamenting in a 2012 speech at a Palestinian refugee camp in Jordan: “In the year I was born, the rope suddenly broke, the world tilted and collapsed, and justice was denied in Palestine. From that year on, your peaceful and beautiful homeland of Palestine was suddenly occupied, massacred, and ravaged by colonialism. 1948 – I didn’t know that I was born the same year as those babies who were expelled from their homes, deprived of their land, and born on the miserable refugee road.”

Zhang was studying at Beijing’s Tsinghua University High School when the Cultural Revolution commenced in May 1966. By his own account he coined the term “Red Guard” in his signature to an anonymous big-character poster, and co-organized the very first contingent of rebel youths by that name – sparking a mass movement that would soon engulf the whole country with Mao’s encouragement. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, the country’s cultural and literary intelligentsia (including many former Red Guards) was dominated by “scar literature” that repudiated the entire experience as a traumatic and nihilistic “ten years of chaos.” Zhang however resolutely bucked the trend, never renouncing his revolutionary idealism and obstinately hewing to what he called the “Red Guard spirit.”

In 1968 he was voluntarily “sent down” to the countryside of Inner Mongolia where he worked at various times as a shepherd and a primary school teacher. Afterwards, with the reopening of institutions of higher education, he enrolled at Peking University to study archaeology with a particular focus on China’s national minorities and on the history of Japan. Through his close study of the Jahriyya sect of Chinese Sufi Islam – which had been historically distinguished for centuries by its poverty, asceticism, and resistance to dynastic authority – he reconnected with his Hui Muslim heritage and experienced a religious awakening. He converted in 1987, explaining that “a beautiful thread links the Red Guards with the Jahriyya … As a Red Guard, [when I found the Jahriyya] I found my real mother among the people.”

Zhang spent the next four years writing an exhaustive chronicle of the Jahriyya, History of the Soul, which became a somewhat unlikely bestseller in the early 1990s. During his aforementioned 2012 visit to five Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan, he personally donated $100,000 in proceeds from a limited-edition reprint of this book to 470 families, recalling in his speech that Muslims of diverse sects and backgrounds from all across China had contributed as a form of zakat (almsgiving). By then his political trajectory – as an unrepentant ex-Red Guard and (as it were) “born again” Muslim – had thoroughly convinced him that global Islam was a critically underappreciated and under-studied pole of resistance to Western imperialism, and indeed had been one since the Crusades.

Throughout the early 2000s Zhang penned a series of searing indictments of Israel’s murderous assaults on Gaza, in terms whose relevance to the current genocide are wholly undiminished. Writing in 2009, he drew an analogy to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising that closely anticipated martyred poet Refaat Alareer’s comments a day after October 7, on the “Gaza ghetto uprising against a hundred years of European and Zionist colonialist occupation”:

In 1943, Mordechai, a young man holding a grenade, stood up to the Nazis in the ghetto (apartheid area) of Warsaw. However, Mordechai today is no longer a Jew, but a Palestinian living in a ghetto called Gaza. Countless young people who support Hamas in its fight with Israel are today’s Mordechai. The enemy they face is no longer the Nazis, but the Nazi-fied Israel.

In 2014 Zhang reflected on the agony of grieving Palestinians in Gaza, broadcasting their loved ones’ maiming and martyrdom in real time as an act of guerrilla resistance to the Zionist information war:

In the footage captured by Gaza refugees on their mobile phones, corpses are piled up, blood is splattering, people are crying, and children are wailing in horror at their broken legs … Can a civilized magazine print rows of baby corpses wrapped in shrouds? Can today’s readers accept photos of fathers crying while holding the bodies of their little daughters whose legs or arms were blown off, whose intestines were blown out? Even though the media does not act as an intermediary, news still spreads rapidly. Every tear, every drop of blood, and every speechless corpse is spread in despair and subconsciously. It is sent to Tencent, Facebook, and all networks. It is sprinkled with salt into the sea and spread to thousands of homes around the world.

In the same piece he almost seems to anticipate by a decade South Africa’s landmark decision to haul Israel before the International Court of Justice for the crime of genocide:

They seem to know that ‘moments’ are fleeting. They seem ready to head to the International Court of Justice. They believe more than others that justice is not dead … As if to echo my feelings, in the South African demonstrations that broke out immediately, Black people held high placards that read: ‘Gaza! Your courage and your firm belief make us ashamed!’

Given his lifelong solidarity with the Palestinian resistance – holding steadfast through all the historic permutations of official Chinese diplomacy – and his extensive experience in Japan, it was only natural that Zhang Chengzhi would pen an eloquent tribute to the Japanese Red Army and its leader Fusako Shigenobu. It is worth reading in full; even machine translation can barely dull his electric prose. But we choose to highlight here one particular passage, where he situates the JRA’s solidarity with Palestine as a world-historic rebuke of Japan’s sordid colonial history and past betrayal of the pan-Asian project:

The twentieth-century revolution was the only—and I mean the only—rebuke of Japanese militarism and of five centuries of global colonialism and imperialism. At the same time, facing the sinister history of Japan’s 150-year history of enslaving its neighbors in Asia, only the ‘Arab [Japanese] Red Army’ went against the grain and rebelled, defying Japan’s colonial project of ‘leaving Asia to join Europe.’ As the name suggests, the Arab Japanese Red Army was a group of sons and daughters of Japan who threw themselves into the Arab world, that is, into the embrace of Mother Asia.

Elsewhere Zhang had written of his deep regret that the Cultural Revolution had taken such an inward turn in practice, depriving him of the opportunity to emulate the JRA and throw himself directly into the revolutionary battlegrounds of Vietnam and Palestine:

We didn’t know at the time that we were rallying the leftwing and progressive students of countless countries across the globe into a great tide of global righteousness … It had two nuclei: the Vietnam War and global support for the Palestinian liberation movement. But the strict regulations of the political education I received up to the age of eighteen meant that I was incapable of imagining or participating in this.

And it did not escape his attention that the JRA’s return to “the embrace of Mother Asia” was rooted in a spirited and militant defense of the Chinese Revolution, and owed it a profound debt for helping to defeat Japanese colonialism:

It was us and the Chinese Revolution that had a strong influence on them. But it must be said that they bravely supported us in turn. After the trial of the Japanese Red Army faction, several memoirs were published stating their original intent to ‘break the anti-China encirclement’ … They also had a complicated side, but they were China’s lifelong supporters and best friends.

Zhang Chengzhi’s forceful interventions continue to leave their mark on younger generations of China’s anti-imperialist left. Zhang Sheng, for instance, reminisced in a message to the author that “this epic anthem of idealism, which the Chinese and Japanese leftists composed using their entire youth and life more than 50 years ago, for the first time played in front of me through Zhang Chengzhi’s words, and largely shaped my nascent understanding of internationalism and Palestinian struggle for liberation in my early age. Therefore, it is definitely not an exaggeration to say that Zhang Chengzhi is the first spiritual teacher of mine on Palestinian studies.”

In 2022, Indian historian and director of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research Vijay Prashad pointedly asked, “Is Asia Possible?” That is to say, can there be a viable progressive pan-Asian project after the original one “burned to a crisp because of Japanese expansionism” and was suffocated by “the tentacles of US imperialism and the malignancies of the Cold War”?

The Japanese Red Army’s salutes to their Chinese comrades, and Zhang Chengzhi’s heartfelt reciprocal tribute, together answer this burning question in the affirmative. In their heyday it was the Palestinian struggle that helped forge a socialist pan-Asianism: uniting liberatory forces from two nations, at the other end of Mao’s “great continent,” that had once been locked in bitter colonial war. As Palestine today returns to its rightful place as the cradle of the world revolution, and the United States musters all the forces of reaction in its drive to extinguish China’s counter-hegemonic challenge, we must never lose sight of this history.

Today in the heart of the empire, progressive forces in the Chinese, Korean, and other Asian diasporas are following in the footsteps of our revolutionary forebears, combating Zionism on all fronts and connecting it to the continued imperialist division of our own homelands. We, like so many millions of others, are building on this rich historical legacy to expand the regional Axis into an “international popular cradle of the resistance.” Let us build and build; then just as surely as Mao predicted, on the eve of the last great world anti-fascist struggle: “Our encirclement, like the hand of Buddha, will turn into the Mountain of Five Elements lying athwart the Universe, and the modern Sun Wukongs – the fascist aggressors – will finally be buried underneath it, never to rise again.”