For several months in 1847 the population of Toronto tripled when close to 40,000 Irish famine refugees arrived at Rees’s Wharf on the city’s waterfront. The majority of these refugees were emaciated, in ill health, and suffering from malnutrition and typhus, which they caught on board the “coffin ships” which transported them across the Atlantic. Toronto’s population at the time was barely 20,000.

Dubbed the “year of the Irish,” this refugee crisis was one of the greatest human challenges in Toronto’s history. With massive numbers of destitute Irish refugees fleeing for their lives, this scenario of desperation was repeated in many other cities along the east coast of North America.

Ireland’s Great Famine (An Gorta Mór in Irish, the “Great Hunger”) was a horrific catastrophe which deeply scarred Ireland. Between 1845 and 1852, more than 1.5 million Irish people starved to death, even while food was being exported by wealthy landowners from Ireland to Britain. Another two million fled in a mass exodus from Ireland. Seventy percent of those who fled across the ocean went to the United States, 28 percent went to Canada, and two percent to Australia.

This was one of the largest displacements of people to occur in the 19th century. Ireland’s population was halved by death and successive waves of emigration, falling from eight million people to four million.

The famine began with a potato blight that destroyed the main food source for poor peasants and labourers. Under British rule, the Irish-speaking part of the population was marginalized and perpetually on the verge of starvation. The loss of this one food staple quickly led to mass starvation and rampant disease. The Gaelic-speaking Irish were seen as dispensable by the British colonizers.

It became a political crisis compounded by the indifferent and uncaring response of the British government. Enough food was being produced in Ireland to alleviate the crisis, but the land was controlled and owned by British landlords. While their tenants starved, landlords were selling and exporting food to England. Landowners evicted, often violently, over half a million tenants from their homes.

Panic developed during the winter of 1846-47, the height of the famine. Between three and four million poor people were at serious risk of starvation, with little relief available or anticipated. The year 1847, dubbed Black ’47, saw the most significant loss of life by starvation and the spread of disease. Unburied corpses littered the rural landscape of Ireland. With people trying to escape almost certain death, significant population movements started taking place. Some went to England or Scotland.

In desperation, many took winter voyages across the Atlantic on overcrowded “coffin ships.” These ships were the cheapest way to cross the Atlantic. They carried the Irish escaping the famine as well as the Highlanders displaced by the Highland Clearances. The ships were crowded, filthy, unsanitary and disease-ridden. Typhus (called “ships fever”) and other diseases were contracted by the refugees due to the unsanitary conditions. Mortality rates of over 20 percent were common on the voyages.

In 1847, 110,000 people left from ports in Ireland destined for Canada. Most emigrants used their entire life savings for steerage fare. Landlords paid the fare for a small percentage to remove them from the land. Canada was the cheapest and quickest way to reach North America. Irish people were British citizens and, as such, could not be refused entry into Canada.

After a gruelling six to nine week journey, 90,000 Irish famine refugees arrived at Québec City, 17,000 at Saint John, and 2,000 at Halifax. Over 440 ships arrived at Québec City in 1847 alone. More than one-quarter of the passengers died en route or from disease by the end of that year. Ports in the United States did not allow disease-ridden ships to dock, so many of the worst coffin ships ended up arriving in Canada.

Surviving the ocean voyage was not the end of hardship. Arriving at ports in North America, the famine refugees were kept on board ships or forced into quarantine or holding centres. Their first stop was often Grosse Île, the quarantine island located in the Gulf of St Lawrence. Grosse Île became the largest burial ground for Irish famine refugees outside of Ireland. Survivors took steamships or barges down the St Lawrence.

“Fever sheds” were quickly constructed in several cities to quarantine the sick and dying, including at Saint John, Montréal, Bytown (Ottawa), Cornwall, Kingston, Burlington Heights and Toronto. These sheds were filthy and contaminated and facilitated the spread of disease. The areas around the sheds were cordoned off to prevent escape.

On Grosse Île, 8,000 Irish famine refugees died in quarantine; 6,000 died in the fever sheds in Montréal; 2,000 died on Partridge Island in the Saint John Harbour; 1,500 in Kingston, and 1,200 in Toronto.

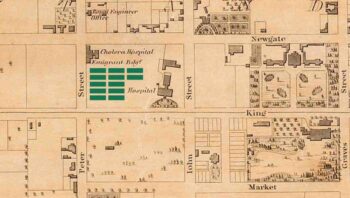

In Toronto, the refugees landed at Rees’s Wharf at the foot of Bathurst Street. At least 12 fever sheds were built by the Toronto Board of Health at the northwest corner of King and John Streets. Workers building the sheds became infected and downed tools, so the sheds were left unfinished without adequate space for the large number of people or without proper sanitation facilities.

Toronto street map showing the ‘fever sheds’ at King and John Streets. (Photo: Canada Ireland Foundation.)

The arrival of the famine Irish in North America had a profound impact. This was one of the largest migrations of people to Canada. It also triggered one of the first major public health crises. As typhus made its way into cities, the new refugees were often blamed. Some places, including Montréal and Kingston, tried to restrict the entry of refugees into their cities.

Amid this unfolding calamity, many people in Toronto and elsewhere did respond with compassion and solidarity. Relief committees were established which raised funds for the famine victims.

Indigenous communities in Canada and the U.S. donated funds. The Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma had lost thousands of their own people to starvation and disease during the Trail of Tears, a forced displacement they had endured several years prior to the Irish famine. They collected money for the Irish, resulting in a special bond which the Irish have maintained with the Choctaw. In 2017, a sculpture was erected in County Cork, Ireland, called “Kindred Spirits,” to commemorate this relationship. The sculpture has nine 20-foot eagle feathers arranged in a circle reaching towards the sky, representing a bowl filled with food.

Toronto’s public health and social services infrastructure came of age in response to the emergency. While assisting the refugees, many caregivers—nurses, doctors, nuns, clergy, medical workers—risked and gave their lives. In Toronto, both the Bishop and Toronto’s medical officer died from typhus.

An unprecedented number of famine orphans ended up in Canada. In an incredible act of compassion, many Irish orphans were adopted into Québécois families. Allowed to keep their Irish surnames, their descendants would go on to play a significant role in Québec society.

The famine victims were buried in mass graves, often called “plague pits,” usually unmarked. In Toronto, some 800 Irish were buried in a mass grave next to St. Paul’s Basilica, on Queen Street east of Parliament. The site was closed in 1857. Today, it is covered over with asphalt and serves as a playground for a neighbourhood school.

The famine hit the west and south parts of Ireland the hardest where most people spoke Irish. Many of the Irish famine refugees were poor and rural. Two-thirds of the Irish arrivals to Canada were Irish monolingual speakers. They had never travelled outside of their local area before. Now they were thousands of miles from home, in an alien environment, not knowing the language, and being greeted with open hostility. They were loathed and despised for being both Irish and Catholic, and were often the victims of racist and violent attacks.

There was a significant Irish presence in Canada before the famine, but most of those earlier migrants had been Protestant and English-speaking. They were deemed to be loyal to Britain and thus more easily absorbed by the fledgling colony. The newer refugees were mostly Catholic, Irish-speaking, and soon encountered the same prejudice and discrimination they had faced back home.

“Irish beggars are to be met everywhere, and they are ignorant and vicious as they are poor,” wrote a columnist in the Toronto Globe, founded by George Brown, a noted Reform politician and later one of the Fathers of Confederation, in Toronto in 1844. “They are lazy, improvident and unthankful; they fill our poorhouses and our prisons.”

Many of the refugees did not stay in Toronto and moved elsewhere. Many headed to large cities in the U.S. such as New York, Boston or Philadelphia and were quickly absorbed into the swelling Irish neighbourhoods.

Those who stayed in Toronto sought accommodation and safety in Corktown and Cabbagetown. While they had escaped the famine, the Irish found grinding poverty, low-paying backbreaking jobs and frequent periods of unemployment in the New World. The competition for jobs led to tensions and violent riots in Montréal, Saint John, and Toronto.

During the same period, African Americans, many of them fugitive slaves, were also arriving in Toronto. Irish, Blacks, Jews and Chinese mingled and lived together in the Ward, the densely packed area in the centre of Toronto that received successive waves of newcomers.

The Globe derided these immigrant areas as being full of “miserable hovels which in themselves are better fitted for pig-styes and cow-pens than residences for human beings.”There was also apprehension about potential subversive elements among them. Back home, the rural Gaelic Irish had formed secret societies such as the Molly Maguires which fomented rebellion against landlords and the wealthy elite. The Molly Maguires were an offshoot of a long line of rural secret societies which included the Whiteboys and Ribbonmen which organized rural resistance, which included resisting evictions. In the aftermath of the famine, Irish people, at home and in exile, founded the clandestine Fenian movement dedicated to establishing an independent Irish republic, by force if necessary.

An emboldened Orange Order, the fraternal order of Irish Protestants, came to dominate Toronto politics for almost a century after the arrival of the famine refugees. The Orange Order’s militant Protestantism and loyalty to empire led to violence against the recent arrivals, earning Toronto the nickname “the Belfast of Canada.”

Many Irish Catholics here and in the U.S. supported the cause of Irish independence from England. Orangemen and Catholics battled annually in the streets both on the Twelfth of July—a bizarre triumphalist commemoration of the Battle of the Boyne, the 1690 victory of William of Orange over the Catholic James II—and on March 17, St. Patrick’s Day.

Rioting got particularly ugly in 1878 in what would be called “one of the wildest nights in the city’s history.” St. Patrick’s Day processions were then outlawed, but not the Twelfth of July.

Incredibly, it took 110 years—until 1988—before March 17 festivities were officially allowed once again in Toronto. By 1988, when the parade was re-instated, St. Patrick’s Day had become commercialized, the Irish had been assimilated, and sectarian tensions were largely a thing of the past, at least in Toronto.

The impact of the famine on the Irish people and the Irish diaspora cannot be overstated. The famine was a watershed, permanently changing the demographics, the politics and the culture.

The legacy of An Gorta Mór—both the famine and emigration—remains a central reference point in Irish consciousness. The famine politicized an already intense anti-colonial struggle against British colonization. Many Irish came to embrace republican movements and causes. Many Irish people continue to show enduring empathy for victims of famine, oppression and injustice around the world, as attested by their strong support for the Palestinian people.

There is a chilling parallel between what happened during Black ’47 and the current refugee crisis. The famine Irish did not want to leave their homeland. They faced the daunting choice either to flee or to starve and perish. The Irish refugees provided cheap labour for well over a century in the Americas, until bosses and the political elite found other, even cheaper sources of human labour to exploit. Still, there remained an enduring backlash against the numbers of poor Irish who swelled the population of cities and towns. The Immigration Act of 1869, legislated two years after Confederation, contained this section: “The Governor may by proclamation, whenever deemed necessary, prohibit the landing of pauper or destitute Immigrants in all Ports or any Port in Canada.”

Today the world is witnessing devastating scenes of famine, starvation, violence, unfathomable loss of human life, unrestrained use of highly lethal weaponry, and massive numbers of desperate people forced to flee for their lives and endure perilous journeys.

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that there are over 110 million forcibly displaced people in the world today, including 36 million refugees and six million asylum seekers. This is the worst refugee crisis since the end of the Second World War. There are over 54 conflicts in the world, most notably the 2.3 million people in Gaza facing starvation and genocide. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) says that refugee deaths were at an all-time high in 2023.

While millions have been displaced, wealthy countries respond with immigration restrictions and buttressed borders. In an increasingly polarized world, refugees and migrants have become a favoured scapegoat. In Canada, a growing number of politicians and media pundits have started blaming migrants and refugees for everything from our domestic housing crisis to our cost-of-living crisis.

Refugees are not a burden, and should not be scapegoated for a myriad of problems that are not of their making. They are people fleeing for their lives and seeking safety and opportunity, just like the famine Irish did. Their rights as displaced people and people seeking asylum need to be protected, and we need to do better at welcoming them.

Ken Theobald’s maternal great-great-grandparents and their four children were among the Irish Famine refugees who arrived in Toronto.