IN his opus The Wealth of Nations published in 1776 Adam Smith drew a distinction between the progressive state, the stationary state and the declining state. The progressive state was one where capital accumulation would be occurring at a rate faster than the growth of population, because of which wages would be high and population growing; in a declining state by contrast the opposite happened, while in a stationary state the capital stock and the population, and hence the labour force, was constant and so were the wages, but at a level lower than in the progressive state. Accordingly he argued: “It is not the actual greatness of national wealth but its continuous increase, which occasions a rise in the wages of labour.” And again “The progressive state is in reality the cheerful and hearty state to all the different orders of the society. The stationary is dull, and the declining melancholy”. North America according to him exemplified a progressive state, while Bengal was a declining state, and China a stationary state.

The contrast that Smith drew between North America and Bengal was a perfectly valid and insightful one at the time. In fact the actual state of Bengal around the time of his writing was far worse than Adam Smith could have imagined: after the East India Company’s acquisition of the diwani over Bengal from Mughal emperor Shah Alam, the revenue demand was so sharply jacked up that it caused a terrible famine during 1770-72, in which 10 million people, approximately one-third of the population of the province, are estimated to have died. But the reason for the contrast between North America and Bengal that Smith gave, why the former was accumulating capital rapidly while the latter was seeing a decline in its capital stock and population, is that North America was governed by the British government (his writing preceded the American war of independence) while Bengal was ruled by a commercial company, namely the East India Company. While this explanation from Smith was not surprising, as he was a champion of laissez faire capitalism and opposed to mercantilist monopolies because of which he loathed the East India Company, it was totally wrong.

When Bengal, and the rest of India that had come under Company rule by then, was taken over by the British government in 1858 after the revolt of 1857, its decline did not stop; the famines did not stop right until independence and the rapacity of the colonial administration did not lessen by an iota. Smith had got the real reason for the contrast between North America and Bengal wrong, which consisted in the fact that the former was a “colony of settlement” while the latter was a “colony of conquest”.

In the colonies of settlement, which were in the temperate regions to which the European population migrated, these immigrants drove the local inhabitants off their lands, herded those of them that survived contact with the Europeans into “reservations”, and took over their lands and habitat to set themselves up as reasonably well-off farmers or in other occupations that came up as a consequence of the multiplier effects of farming. Scholars estimate that around 50 million Europeans migrated from Europe to these temperate regions of white settlement, such as Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, between 1815 and 1914 (migration was occurring even before that but on a smaller scale). What is noteworthy is that while there was an intra-tropical migration of Indian and Chinese populations of roughly an equal order of magnitude over the same period, in the form of indentured or coolie labour, no tropical migrant was allowed unrestricted entry to these temperate countries peopled by European migrants; in fact they are still not allowed unrestricted entry to this day into these countries of the temperate regions.

The migration of population from Europe to the temperate regions was also accompanied by a parallel migration of capital which led to a diffusion of industrial activity to this “new world”; by contrast there was very little diffusion of industrial activity, until recently at any rate, from Europe or from the newly-industrialising countries of European migrants, to the colonies of conquest that were mainly located in the tropical or semi-tropical regions. Whatever capital was invested by the metropolis in these colonies of conquest was for the development of primary commodities that was in keeping with the colonial pattern of international division of labour. For instance, of the total British direct foreign investment at the beginning of the first world war, only 10 per cent had come to the Indian sub-continent which was its largest colony; and that was in areas like tea, jute, and activities related to their exports.

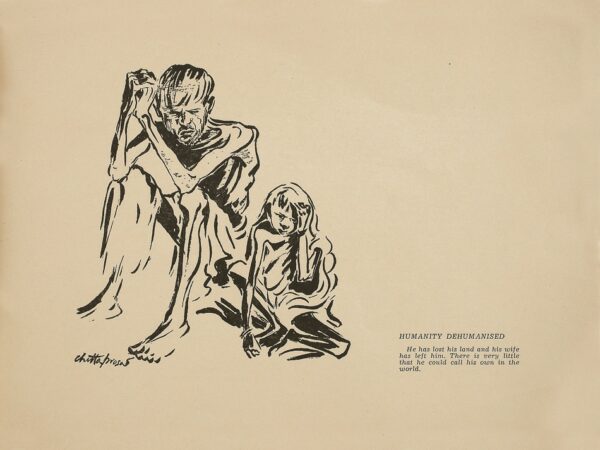

The colonies of conquest were not just victims of the “drain of surplus” that was financed from tax revenue and took the form of the entire export surplus of the colonies being siphoned off gratis to the metropolis, without which it is doubtful if they could have undergone their industrial revolution at all; they also witnessed subsequent decimation of their pre-capitalist industrial activities through the import of manufactured goods from the metropolis. This decimation which is referred to as “deindustrialisation” generated mass unemployment of artisans and craftsmen that increased the pressure on land, raising rents, reducing wages, and engendering mass poverty. Bengal was thus not just a victim of negative capital accumulation as Adam Smith thought it to be. It was the “other side” of the capital accumulation occurring in Britain. And its “declining state” was the result not just of the East India Company’s rule, but also of the growth of industrial capitalism in Britain which eventually required the breaking of the East India Company’s trade monopoly to make larger-scale manufacturing imports from the metropolis into India possible.

All this is quite well-known; the reason for repeating it here is that the distinction between colonies of settlement and colonies of conquest is often not drawn to this day by economists and economic historians, who, while presenting historical data often lump together both kinds of colonies within the term “empire” which serves to obfuscate what was actually happening.

But that is not all. It is often believed that the diffusion of activities from the metropolis to the temperate regions of white settlement that occurred earlier, is now taking place under the neo-liberal regime vis-à-vis the former colonies of conquest, that just as the United States and Canada had developed in an earlier period, countries like India and Indonesia will develop in the current period.

This argument however misses three obvious points. First, countries like India and Indonesia, which had been colonies of conquest, have inherited from the past a backlog of poverty and unemployment precisely because of their having been colonies of conquest; the amelioration of these problems therefore cannot be effected through a mere replication of the temperate countries’ experience of capital inflows from the metropolis. Secondly, these former colonies of conquest still have substantial petty and small-scale production, which simply opening these economies to inflows of capital will further destroy. Instead of using up the labour reserves created by colonialism, which constitutes the sine qua non of development in these societies, inflows of capital would simply cause a further addition to these reserves. And thirdly, during the nineteenth century diffusion of industrial activities to the temperate regions of European settlement, the countries of such settlement had protected themselves strongly; in the case of today’s recipients of such diffusion, the neo-liberal regime prevents any protectionism, which truncates the local multiplier effects of diffusion.

All this moreover is in addition to the fact that the metropolis will not simply sit back and watch the products from these former colonies of conquest outcompete their own domestic production, adding to their domestic unemployment, even if these products are produced by a relocation of metropolitan capital itself. What is happening to China at present, against the imports of whose goods the U.S. has been protecting itself, is highly instructive in this context.

The trajectories of development of the colonies of settlement and the colonies of conquest have been completely different. Adam Smith did not see this, but his oversight could be excused because he was a pioneer who wrote very early. But those who believe that the former colonies of conquest can today follow the same trajectory as the colonies of settlement had done earlier, are wholly mistaken.