The religious struggle in Berlin which ended Sunday with joy for some and great disappointment for others was primarily a political battle, even though it dealt with schools and religious lessons. Many Berliners never did understand the complicated issue. For an outsider to even try, a few German peculiarities need explaining.

First of all, church and state are not separate here. The state helps support theology students preparing for the clergy, it subsidizes church-run kindergartens and homes for the aged, it helps pay for the repair of some churches. Most surprising, perhaps, the government finance office automatically takes a tax, usually 8 or 9 percent, out of every pay check and transfers it to the churches. When you are hired you check off Roman Catholic, Evangelical, which means Lutheran here, or (very rarely) Jewish. You can also check “none of the above,” but if you were ever baptized you get taxed, unless you go to the town clerk and quit the church (which also means no church weddings, churchyard burials, or other perks). This assistance to the churches goes back to 1827.

The other main surprise: schools have religious classes as part of their regular curriculum, taught by teachers designated and trained by the Roman Catholic, Evangelical, Jewish, or Moslem churches (or, theoretically, Free Thought advocates, which means atheist). Parents make the choice. And these classes are graded on report cards just like History or Arithmetic.

|

“Türkischer Bund: Nein zu Pro Reli” (TV Berlin Video) |

But not in the two city-states, Bremen and Berlin, which opted out of this practice. In Berlin, religious classes in the different faiths, though still offered from the first grade on, are completely voluntary. Then, three years ago, Berlin’s coalition government of Social Democrats and The Left introduced a new course called Ethics, as a part of the regular curriculum for seventh to tenth grade students. Inspired in part by the “honor killing” of a young Turkish woman by her brother because of her supposed immorality, Ethik aimed at free, open discussions of questions like moral values, tolerance, equality, and solidarity. It also intended to discuss all major world religions, encouraging open-mindedness towards other faiths and overcoming prejudices between Christian children and those of immigrant, usually Islamic background, currently 43 percent of the Berlin total. The courses were also seen as antidotes to all such forms of hatred as anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.

Most students seemed to like the classes. But since they were mandatory, while additional courses with the religious teacher of their own faith were voluntary, many considered the two weekly hours of Ethics as sufficient and did without the others. This applied to about half of all seventh to tenth graders, many of them not religious at all in a city often scorned as Germany’s “atheist capital.” This is largely true because one third of the city was part of the GDR, where religion was taught only at church Sunday schools and never in the schools. After East Germany was annexed to West Germany in 1990 (known as “reunification”), the churches expected a rapid increase in membership by “oppressed” East Germans, whom they believed had been forcibly kept from religion. But the surge was very disappointing: only about a third of the East Berliners are willing to face the steep church tax on their pay checks, and the trend has been seeping into western Germany. Both main churches are seriously strapped for cash and fear losing the hearts and minds of even more young Berliners.

Not a few progressive pastors favor the Ethics lessons, so do the Greens, although they oppose the present Berlin government. It is an open question whether even the very conservative church leaders would have initiated the kind of struggle which just came to at least a temporary end. The man who started it, a largely unknown Catholic lawyer named Lehmann, was an unsuccessful figure in the local Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the party of Angela Merkel, which was thrown out of office in Berlin after a financial scandal and is passionately interested in regaining popularity and power.

The first main effort utilized Berlin’s very liberal laws on initiatives and referendums. Last year the CDU collected enough signatures to force a referendum on saving Tempelhof Airport. Situated dangerously in the middle of town and a potential if minor rival to the huge new airport being built outside the city, it conjures up nostalgic Western visions of its key role in the 1948 Berlin Airlift, a major event in the early cold war era. (For some it conjured up older visions as a major Nazi propaganda landmark.) Hinting broadly at the cold war angle, the Christian Democrats hoped the referendum would discredit the coalition government of Social Democrats and the Left by reviving and strengthening the antagonism of many West Berliners toward “those dreadful Reds in the eastern boroughs,” once the capital of the (East) German Democratic Republic. In the end, few East Berliners gave a hoot about the old airport and didn’t vote. So many West Berliners also stayed home that the required quorum of voters was not met and the referendum failed.

|

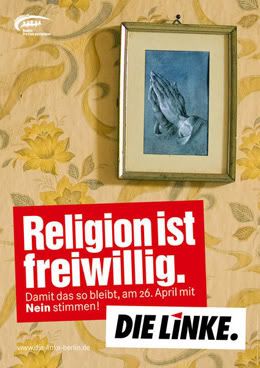

This new attempt, known as Pro Reli (for religion), basically repeated the same strategy, first with an intense petition campaign calling for free choice between Ethics (pupils together) and Religion (pupils divided by faith). Although the existing rules, which would be maintained by a “No” vote, never prevented a single student from going to separate religious classes if desired, it did require that all pupils join together in the Ethics course, in a conscious move to overcome prejudices. But the Pro Reli forces plastered the whole city with posters and billboards (later partly balanced by the Pro Ethik posters) stressing “Freedom of Choice” and, since this was a bit complicated, simply “Freedom.” Election Sunday was even called “Day of Freedom” on some billboards, and TV interviewers quoted elderly voters insisting that “This is a Christian country after all, with Western Christian traditions.” Thus, a tacit message, at least for some voters, was directed against “Easterners,” atheists, leftists in the state government, but also Muslims, Jews, and other “non-Christians” (although the Berlin Jewish congregation, like Chancellor Angela Merkel, supported the Pro Reli referendum). One surprising supporter of religious classes as an alternative to Ethics was the moderator of the German equivalent of “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.”

But alas for all such supporters, Sunday was a beautiful sunny day. Most people went to the park, the many lakes, two zoos, or other outdoor sites. Many admitted to TV interviewers that they didn’t understand the complicated business and didn’t really care. Only about a third of all citizens went to the polls and the required quorum was not obtained. In most West Berlin boroughs about 60 percent voted Pro Reli, in most East Berlin boroughs about 70 percent voted Pro Ethik, but the total sum was too small. To the dismay of Pro Reli supporters, even among those who did vote the “Ja” Pro Reli side won only 48.5 percent, while the Pro Ethik “Nein” voters got a majority of 51.3 percent.

Lehmann and the Roman Catholic Cardinal admitted their disappointment but refused to give up. The right-wing crowd has already begun to think up new attacks. But although many millions of Euros were spent in their effort, the antagonism, passions, or even hatred which might have resulted were luckily absent, and most people simply enjoyed a beautiful day. The status quo remains, and it will be up to both Pro Reli and Pro Ethik advocates to make their school courses as attractive as possible.

Victor Grossman, American journalist and author, is a resident of East Berlin for many years. He is the author of Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany (University of Massachusetts Press, 2003).