For the most part, we go along living without thinking much about the world around us. Things just seem to happen without rhyme or reason. My parents knew that people like themselves were not quite the same as people who had a lot more money, but they didn’t reflect very deeply as to why this was so. They might say “the little guy always gets it” or “the rich get richer” or, as my mother often said, “tutte matte” (everybody’s crazy). These bits of folk wisdom help people rationalize their circumstances, though they don’t explain anything. Naturally the powers that be do not mind the mutterings of the poorer classes, as long as they do not lead to any actions. And these same powers do all they can to create a thick layer of fog between social reality and the truth. They do this through their control of and influence over the mass media, advertising, the government, and the universities.

Sometimes, however, something so shocking happens that it tears away the veil that hides the truth, exposing reality in all of its brutality and compelling people to take action. In my parents’ generation, it was the Great Depression, which revealed the inner workings of the “invisible hand” and showed the horrors of which the market system was capable. The rhetoric of individualism and free choice quickly rang false, and working people began to organize collectively to stop their suffering.  In my era, the Vietnam War served as the exposing agent. The myths surrounding the origins and history of the United States came under scrutiny, and it was revealed that our nation was not now and never had been the knight in shining armor it had been portrayed to be. We saw the war on television and read about it in the mainstream media, which despite their unwillingness to probe very deeply, still could not hide the crimes being committed by the United States.

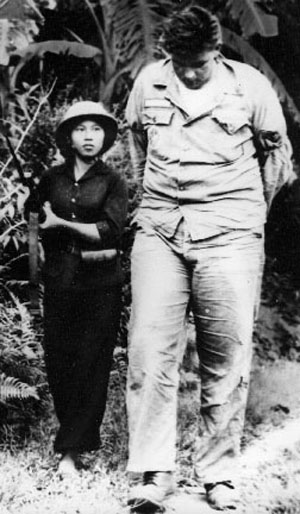

In my era, the Vietnam War served as the exposing agent. The myths surrounding the origins and history of the United States came under scrutiny, and it was revealed that our nation was not now and never had been the knight in shining armor it had been portrayed to be. We saw the war on television and read about it in the mainstream media, which despite their unwillingness to probe very deeply, still could not hide the crimes being committed by the United States.  Our soldiers bombed Vietnamese hospitals, assassinated civilians, and massacred innocent villagers. They also killed their own officers, refused to obey orders, and deserted. Returning soldiers told us what they had done. Kids from my hometown came back mentally dead and addicted to drugs. One marine told me how he had refused an order from his sergeant to kill a young girl running across a field. Another came back insane; I remember one night when he calmly asked me to go with him to confront and perhaps kill a guy we knew who had drugs but wouldn’t give him any. Those who studied the sordid history of the war began to take a critical look at other aspects of U.S. history, from the American Revolution to slavery to the labor movement to the Cold War to the oppression of women. They began to uncover a hidden history which they then used to construct alternative theories of our society. Their new knowledge formed the basis for their escalating confrontation with the government over the war.

Our soldiers bombed Vietnamese hospitals, assassinated civilians, and massacred innocent villagers. They also killed their own officers, refused to obey orders, and deserted. Returning soldiers told us what they had done. Kids from my hometown came back mentally dead and addicted to drugs. One marine told me how he had refused an order from his sergeant to kill a young girl running across a field. Another came back insane; I remember one night when he calmly asked me to go with him to confront and perhaps kill a guy we knew who had drugs but wouldn’t give him any. Those who studied the sordid history of the war began to take a critical look at other aspects of U.S. history, from the American Revolution to slavery to the labor movement to the Cold War to the oppression of women. They began to uncover a hidden history which they then used to construct alternative theories of our society. Their new knowledge formed the basis for their escalating confrontation with the government over the war.

Opposition to the war was not confined to the elite private and public universities, although it was slow to reach the backwaters of Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Today Johnstown is a shell of its former self, but in 1969 it was still a prosperous mill town. Townspeople, including most workers, were conservative and patriotic, and this was true also of the campus community. In 1970, I was asked to attend a meeting of supervisors from the Bethlehem Steel plant in which they were discussing civil rights legislation. What a band of bigots! They believed that black people were being given special advantages by the new laws. I got into an argument within 30 minutes. One man asked me if SDS (Students for a Democratic Society — an important radical student group) was agitating on campus. I said that I could only wish that they were, which did not endear me to the group. All that our campus had managed was a peaceful demonstration against the war during the great anti-war mobilization in the Fall of 1969. My war veteran students were upset that I had canceled class in support of the national protest, and I noted with dismay that I was the only teacher who did. Later, a history professor and former army colonel was so incensed over my anti-war remarks to the student newspaper that he confronted me in public and said that he had been personally insulted by my comments. With the arrogance of righteous youth, I suggested that perhaps the best way for us to settle our differences was with a duel. Some of the students who were sympathetic to my views began to sneak radical literature into his faculty mailbox.

The highlights of our protest were a recitation of the names of the U.S. soldiers killed in the war and a reading of anti-war poetry by the Spanish instructor. Some of the poems were in Spanish, so the teacher had handed out mimeographed pages containing the translations. We were sitting on benches underneath the flagpole, a tiny minority of students and a couple of faculty. I remember being moved by the reading of the names and the poems. I had been learning about the Vietnamese, and I grieved for their suffering and wished with all my heart that they would defeat us as they had the French. I hated everyone responsible for the war, and I hoped that Johnson, Westmoreland, and all of the other war criminals would die horrible deaths. I yearned for the courage to run the Vietcong flag up the pole, and I wondered why, to placate my mother, I had not had the courage to speak against the war in the park in my hometown. I hardly noticed that a group of students, some of them my own and all of them veterans, were approaching our group. They rushed us, grabbed the poetry translations from our hands and ripped them up. Then just as suddenly they were gone.

On a bulletin board in my office there is a faded and yellow newspaper clipping. It was taken from an old issue of the now defunct Guardian newspaper. The headline says in large bold letters, “Victory in Vietnam.” My students no longer have any idea what the headline means. But it means a great deal to me. It honors the victory of the Vietnamese in the war. And I honor the Vietnamese people by keeping it on display. It serves as a reminder to me that this most horrible war was my greatest teacher, for through it I came to understand the world, including the world of work, more clearly, more radically, and, I hope, with a more humane spirit.

On a bulletin board in my office there is a faded and yellow newspaper clipping. It was taken from an old issue of the now defunct Guardian newspaper. The headline says in large bold letters, “Victory in Vietnam.” My students no longer have any idea what the headline means. But it means a great deal to me. It honors the victory of the Vietnamese in the war. And I honor the Vietnamese people by keeping it on display. It serves as a reminder to me that this most horrible war was my greatest teacher, for through it I came to understand the world, including the world of work, more clearly, more radically, and, I hope, with a more humane spirit.

Michael D. Yates is associate editor of Monthly Review. He was for many years professor of economics at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. He is author of Longer Hours, Fewer Jobs: Employment and Unemployment in the United States (1994), Why Unions Matter (1998), and Naming the System: Inequality and Work in the Global System (2004), all published by Monthly Review Press.