The consumer price index rose 0.2 percent in January as energy prices continue to drive a wedge between the overall and core rates. Energy prices jumped 2.8 percent (a 40 percent annualized rate) in January. The core index of inflation, however, fell 0.1 percent in the month — the first such fall in 27 years.

With this month’s revisions to the seasonal adjustment factors, the overall rate of inflation nevertheless continues to decline. The 2.3 percent annualized rate over the last three months is below the 3.0 percent for the three months ending in October and well below the 3.7 percent for the preceding quarter.

In addition to energy prices, medical care prices grew 0.5 percent in January after December’s modest 0.1 percent gain. Over the last three months, medical prices have risen at a 3.8 percent annualized rate, with services — notably hospitals — leading the way. The price of hospital services has increased steadily over the last year and now stands 6.8 percent higher than twelve months ago, reflecting greater pressure on the part of state and local budgets.

Also adding to price pressure was a 1.3 percent rise in transportation costs, in large part due to higher fuel prices. A 0.5 percent fall in new vehicle prices was balanced by a 1.5 percent rise in used vehicle prices. In the last six months, the price of new and used motor vehicles has grown at a 6.4 percent annualized rate. Public transportation, despite a 1.8 percent fall in January, has grown at an 11.0 percent annualized rate over the last six months, also in part due to the rise in fuel prices.

Core prices have remained unchanged over the last three months — a 0.007 percent annualized rate — after averaging a 1.7 percent annualized rate over the previous two quarters. The main reason for the restraint in core prices is an ongoing drop in shelter prices due to fallout from the bubble-driven oversupply of housing.

Continued falls in shelter prices more than balanced out the rise in commodity prices. Shelter prices fell 0.5 percent in January (2.6 percent annualized since October.) Rent prices held steady and owners’ equivalent rent fell 0.1 percent for the third time since September. Owners’ equivalent rent fell at a 0.7 percent annualized rate over the last three months.

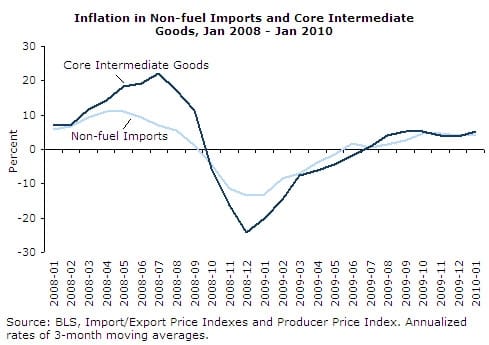

Non-fuel import prices grew 0.4 percent in January and at a 4.0 percent annualized rate over the last three months. The growth in non-fuel import prices has been entirely due to non-fuel industrial supply prices, which grew at a 20 percent annualized rate since October.

Industrial supplies account for less than one-fifth of the non-fuel import price index, yet added 3.1 percentage points to the three-month inflation rate of non-fuel imports. The price of capital and consumer goods, by contrast, fell at a 0.7 percent annualized rate for the three months ending in January.

These higher imported supply costs continue to pressure prices at early stages of production. Driven by price increases for materials used in non-food manufacturing, the price index for intermediate core commodities rose 0.5 percent in January and has now grown at a 5.2 percent annualized rate over the last six months.

With energy and commodity imports the building forces behind inflation, the Federal Reserve would be ill-advised to raise interest rates in response to these price pressures. The real hourly wage of production and non-supervisory workers fell $0.01 again in January, down $0.08 cents over the last year.

While rent prices have kept overall inflation in check, the price of medical care continues to see steady growth. This is a constant reminder that excessive inflation in medical care poses a major threat to the long-run health of the economy and that the need for real reform of the health care system is with us whether or not this Congress passes a health-insurance bill.

David Rosnick is an economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C. He received his Ph.D. in Computer Science from North Carolina State University and his M.A. in Economics from George Washington University. This article was first published by CEPR on 19 February 2010 under a Creative Commons license. See, also, Paul Krugman, “Disinflation” (Conscience of a Liberal, 19 February 2010):

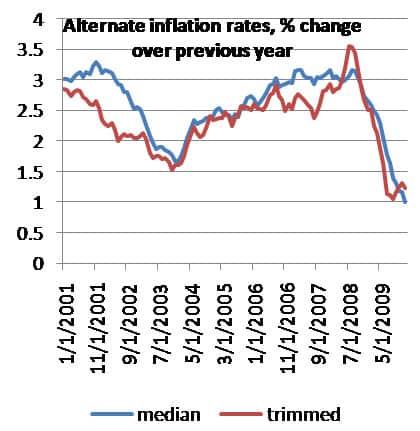

What I find myself looking at these days are the Cleveland Fed “trimmed” inflation measures, which exclude outlying large price movements; the ultimate trim is the median, the rise in the price of the median category. And these indicators tell a story of dramatic disinflation in the face of a week economy:

I find this a scary picture. For one thing, it suggests that deflation may not be too far in the future. But beyond that, there’s a growing belief among sensible economists that we need higher, not lower inflation. What we’re doing now is moving in the wrong direction, with real interest rates rising even as the nominal rate remains at zero.

|

| Print