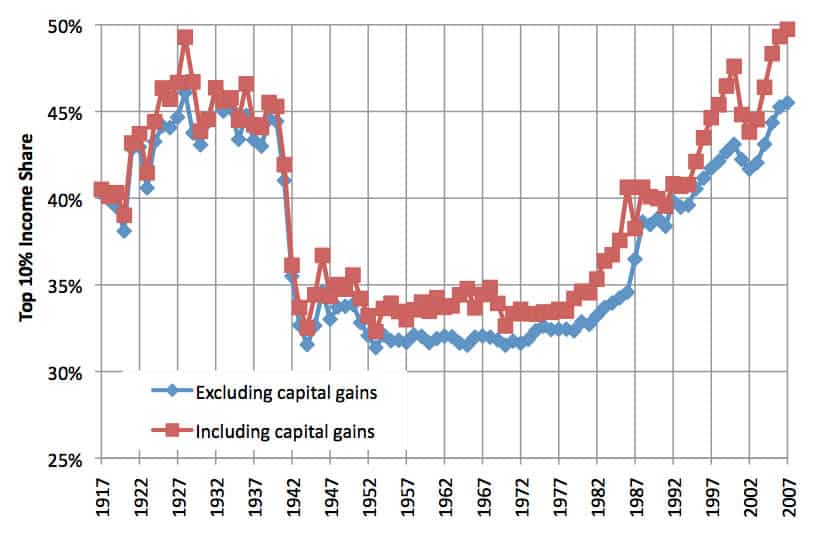

The gap between annual incomes of the top 10 per cent of US citizens and what the other 90 per cent gets has been widening sharply for the last 30 years. The nation’s economic development has been increasingly divisive. Professor Emmanuel Saez of the University of California at Berkeley, a leading expert, summarizes the facts on his website, from which the graph below is gratefully taken.

This graph shows how the top 10 per cent of income earners in the US took home, after the 1970s, an ever more outsized share of the total national income. That top 10 percent had already taken 30-35 per cent of total national income between the early 1940s through the 1970s. Thereafter they took ever more until reaching their current level of 45-50 per cent.

Income inequality in the US is now greater than it has ever been over the last century. From 1980 to 2007, the US became a far more unequal society.

Income inequality — and especially rapidly rising income inequality — provokes envy, resentment, and tension in a society. They lie behind the more visible signs of bitter hostilities inside the US: for examples, talk radio outrages, harsh debates in legislatures, nasty outbursts at tea parties and by loose-lipped politicians, and surprising election outcomes.

There is no mystery about why income inequality got so much worse. The real wages of average workers stopped rising during the 1970s (after having risen for a century or more). Meanwhile those workers’ productivity kept rising: they produced ever more goods and services for their employers to sell. However, employers no longer had to raise wages to get that extra output from them. Employers and those they support (share-holders, top managers, professionals, etc.) thus “earned” ever more because workers’ incomes stagnated.

Most American workers have not understood, nor were they informed, why they were falling ever further behind the wealthy top 10 per cent. They did not grasp that their decline flowed from changed social conditions that ended the tradition of rising wages for rising productivity. First among those conditions were thecomputers that replaced so many jobs and the employers who moved ever more jobs outside the US to lower wage locations. Second, there were the millions of US housewives and immigrants newly looking for paid work in the US after the 1970s — out of necessity and desires for better lives. The US labor market thus experienced a combination of shrinking demand for workers just as more workers looked for jobs. Employers from Main Street to Wall Street took advantage of the changed conditions. They stopped raising the wages paid to their US employees. Nothing personal; it was just business; it was the way the system works.

The employers’ computerized workplaces pressured more work out of their employees so their productivity kept rising. By no longer paying the workers any more, employers kept the entire productivity gains for themselves, their share owners, their top managers, and their skilled professional subordinates. So this group, the top 10 per cent of Americans, kept gathering more of the nation’s annual income into their hands as the graph above shows.

Few among the lower 90 per cent understood how the changed social conditions combined with the economic system to cause their falling income shares. Instead, many blamed themselves or friends and family or found still other scapegoats. Workers who blamed themselves then suffered from damaged self-esteem and all its tragic consequences. Those who turned in frustration on friends and families suffered from strained intimate and personal relationships and their painful results. And those who scapegoated still others (immigrants, politicians, and, after 2007, bankers and Wall Street) not only over-reacted to them but, more importantly, missed a chance to see and solve the problems of the economic system rather than ineffectively fiddling with one or another of its parts.

What malfunctioned over the last 30 years was the economic system; it generated a divisive, depressing, and dangerous pattern of economic development. It was the system of production — where employers and employees endlessly seek advantages at each other’s expense — that stopped raising workers wages. It was the financial part of the system that pushed unsustainable loans and risky speculations as part of the endless competition among banks, hedge funds, insurance companies, etc. It was the political part of the system that looked the other way (instead of regulating) or passed laws to please those who increasingly throw money at the best government money can buy. It was also the fact that the mass of workers as well as investors were hypnotized by the system’s logic and bowed to its endless pressures to consume, borrow, lend and profit.

After all, the leading ideologues in the US — politicians, media personalities, and academics — had mostly bought into the system with enthusiasm. They all but drowned out the voices of critics who saw systemic problems. They denounced or ignored those who advocated a change of economic system as part of the needed solution.

Attacks on scapegoats are distractions from facing and dealing with the system that shapes what scapegoats do. To remove this or that scapegoat while leaving the system in place is no solution. For example, punishing or even excluding immigrants from the US will not likely raise domestic wages. Given the system driving US employers to profit from low wages, they will likely react by moving more jobs to lower wages countries. Punishing US bankers will only shift the location of risky financial deals to other institutions inside or outside the US. Regulations constraining what private enterprises can do for profit only provoke them further to manipulate and/or corrupt politicians to evade, alter, or remove the regulations. The system works that way and normally compels its parts to do likewise. That is what “system” means. But a systemic crisis like today’s is “abnormal,” a window onto possible system-change that would be terrible to waste.

Rick Wolff is a Professor Emeritus at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst and also a Visiting Professor at the Graduate Program in International Affairs of the New School University in New York. He is the author of New Departures in Marxian Theory (Routledge, 2006) among many other publications. Check out Rick Wolff’s documentary film on the current economic crisis, Capitalism Hits the Fan, at www.capitalismhitsthefan.com. Visit Wolff’s Web site at www.rdwolff.com, and order a copy of his new book Capitalism Hits the Fan: The Global Economic Meltdown and What to Do about It.

|

| Print