Government policy makers, no matter the party in power, like to project a rosy future. However, claims of economic renewal, absent fundamental changes in the structure and workings of the US economy, should not be taken seriously. The fundamental changes I would advocate are those that would: dramatically boost worker power; secure a progressive and growing funding base for a needed expansion of public housing and infrastructure and public spending on health care, education, and transportation; and end the production and use of fossil fuels and significantly reduce greenhouse emissions.

Fundamental changes are needed because the United States is suffering from an extended period of slow and declining growth, what is known as secular stagnation.

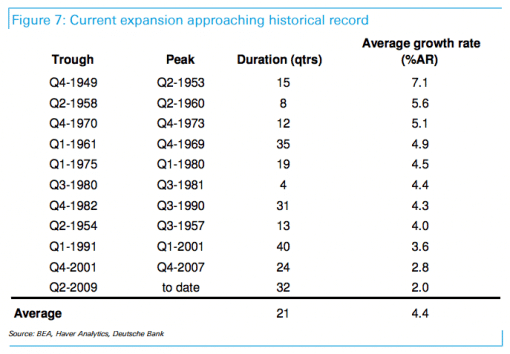

The following figure, taken from a Financial Times blog post, shows the duration and average rate of growth of every economic expansion in the postwar period. The current expansion, which started in the second quarter of 2009, is the third longest, although soon to become the second. Among other things, that means that a new recession is likely not far off (especially with the Federal Reserve Board apparently committed to boosting interest rates).

As we can see, the current expansion has recorded the slowest rate of growth of any expansion. Moreover, as Cardiff Garcia, the author of the blog post, points out: “Also worrying is the observation from the chart that every subsequent expansion since 1970 has grown at a slower pace than its predecessor, regardless of what caused the downturn from which it was recovering.”

Michalis Nikiforos and Gennaro Zezza begin their Levy Economics Institute report on current economic trends as follows:

From a macroeconomic point of view, 2016 was an ordinary year in the post–Great Recession period. As in prior years, the conventional forecasts predicted that this would be the year the economy would finally escape from the “new normal” of secular stagnation. But just as in every previous year, the forecasts were confounded by the actual result: lower-than-expected growth—just 1.6 percent.

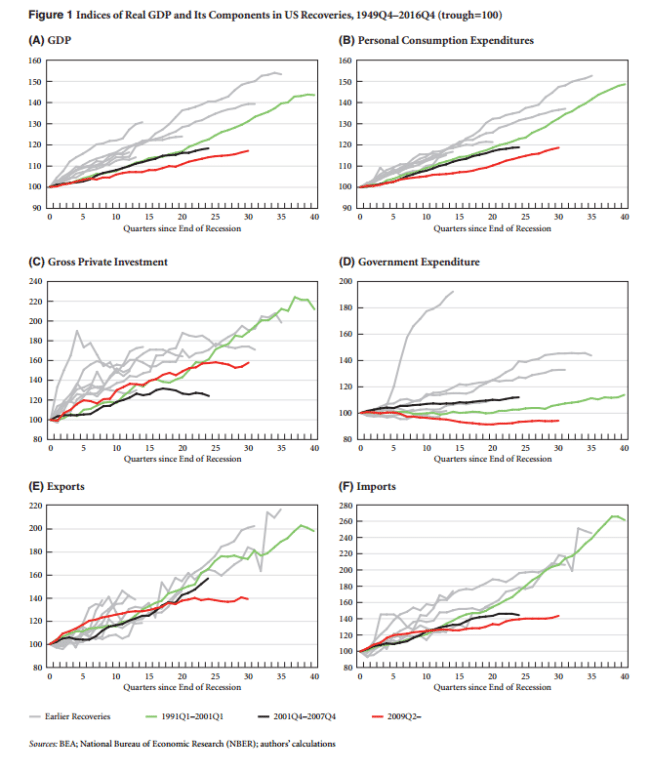

The following figures illustrate the overall weakness of the current expansion. Each figure shows, for every postwar expansion, a major macro indicator and its growth over time since the end of its preceding recession. The three most recent expansions, including the current one, are color highlighted.

Figure 1A makes clear that growth has been slower in this expansion than in any previous expansion. Figure 1B shows that “real consumption has grown only about 18 percent compared to the trough of 2009—similar to the expansion of GDP—and also stands out as the slowest recovery of consumption growth in the postwar period.”

Perhaps most striking is the actual decrease in real government expenditure shown in figure 1D. Real government expenditure is some 6 percent lower than it was eight years ago. In no other expansion did real government expenditure fall. Without doubt austerity is one of the main reasons for our current slow expansion.

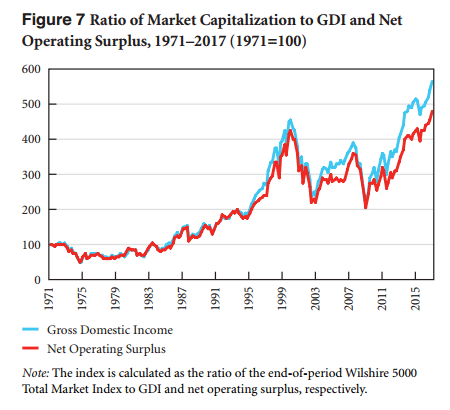

Significantly, as we see in figure 7 below, the stock market has continued to boom in spite of the weak performance of the economy. This figure shows that the total value of the stock market has risen sharply, regardless of whether compared to the growth in personal income or profits (measured by net operating surplus). This rise has generally kept those at the top of the income pyramid happy despite the country’s weak overall economic performance.

No doubt, on-going wage stagnation, which has depressed consumption, and privatization, which has grown in concert with austerity, has helped to fuel this new stock market bubble. One reason top income earners have been so favorable to the broad contours of Trump administration policy is that it is designed to strengthen both trends.

Recession will come. In an era of secular stagnation that means the downturn will hit an already weak economy and struggling working class. And the upturn that follows will likely be weaker than the current one. Market forces will not save us. Real improvements demand transformative policy changes.