What is the relation between power in the military realm and in the political one? Between prowess, inventiveness, and responsibility in one context versus the same qualities in the other? These questions come to a head for me—a Bolivarian Marxist traveling in Nepal to learn from its revolutionary process—after meeting with Vice President “Pasang” (Nanda Kishor Pun), who was once commander of the People’s Liberation Army.

To meet the Vice President, my companion and I are led by a protocol officer into a comfortable office lounge in a building beside Nepal’s Electoral Commission. There are a few assistants in the room. Pasang soon enters dressed in a neat blue suit with a Nepal flag pin in his lapel. He is welcoming and friendly, responding very briefly to my questions about his views on the role of morale in revolutionary war and whether there are any universal lessons to be drawn from Nepal’s recent struggle.

Quickly changing the subject, the Vice President asks if there is peace in Venezuela, to which I say, yes, for more than a year there has been relative peace. It soon becomes clear from Pasang’s manner that we are in a very official context and will not be delving deeply into either revolutionary military practice or politics. In fact, during the whole meeting, the only indication that the VP comes from a Marxist background are a few fleeting remarks made about the shared struggle of Nepal and the Latin American countries against capitalism…

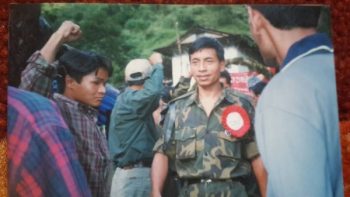

The formal courteousness of this one-time revolutionary commander is itself food for thought. Unlike other key Maoist leaders, who have separated from Prachanda’s hegemonic tendency, Pasang has followed the latter in forming Nepal’s new ruling party through a fusion with UML, the traditional communist party. Pasang was probably the most impressive military leader to emerge in the People’s Liberation Army. He is famous for brilliantly haranguing his troops before battle. These were often informal, even “green” troops, who are said to have maintained high morale and carefully followed their commander’s instructions in the most difficult battles.

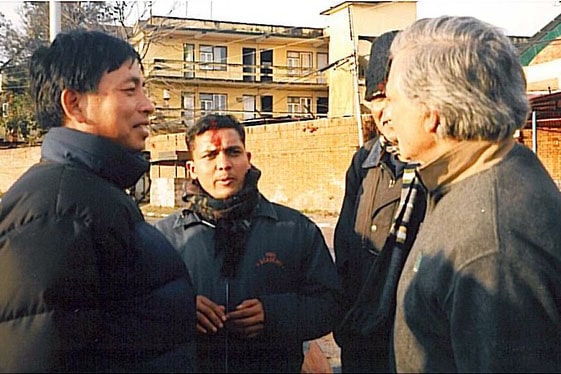

From left to right: Nepal Vice-President Nanda Kishor Pun (Comrade Pasang), Comrade Prayas (translator), MR author Bernard D’Mello, and Monthly Review Foundation Vice-President John Mage, in February 2007.

The People’s War here lasted ten years, from 1996 to 2006, and Pasang was a key player in all of it. His first engagement targeted a police post in Holeri in 1996 and was carried out almost without arms (one rusty Enfield .303 and some homemade grenades). Later on, along with fellow division chief Ananta (Barsaman Pun), he came to command more regular troops. Engagements were always seen in political terms, with a military action sometimes being valued as much for its “propaganda effect” as for its strictly concrete results. Before attacking the district headquarters Beni, Pasang’s most successful action, he reminded his troops about the need for sacrifice: “Each of you must feel personally responsible for bringing the battle to a successful end.”

My meeting with him, despite or really because of its amiable, pro forma character, leaves me wondering about the apparently incongruous relation between the former military commander whom some viewed as a the General Giap of his times and today’s easygoing and seemingly traditional politician. It raises all kinds of questions—without answering them—about the lines that can be drawn between the military and the political spheres. How does one transition between the two? What do power and authority mean in each context?

The central question can be framed in terms of military theory: Clausewitz famously said that war is the continuation of politics. Yet for Nepal’s revolutionaries, who entered a drawn-out and not-very-satisfactory peace process some ten years ago, the problem goes in the opposite direction. How can politics be a way of pursuing the same goals once pursued in war? And through what form of politics? Or is the transition an abrupt “beaming up” process between two highly autonomous realms?

Maoist leader Baburam Bhattarai, who split four years ago from the hegemonic Prachanda tendency, insists that Nepal’s revolutionary movement was forced into a compromise in 2005-6. The Maoists were compelled to do so, he thinks, because otherwise there would have been a direct imperialist intervention (probably from the US, but possibly from an expansionist India acting on the former’s behalf). However, according to Baburam, having made that compromise, which resulted in an incomplete revolution, the party should have then developed a new strategy. In effect, it had the burden of conceiving a new way of going forward.

This certainly sounds like the voice of reason, and it resonates with Lenin’s claim that sometimes one has no choice but to compromise—like when an armed robber says “your money or your life.” Such situations require taking stock of the real situation (now you are without money, but with your life) and going forward. So Baburam, even if he’s wrong about other things, is surely right to criticize those in the movement who simply glossed lightly over the compromise that was made and now merely talk victory rather than assuming the difficult work of thinking about how to go forward in a new scenario.

Another clue to the present situation in Nepal was explained by Baburam’s longtime theoretical opponent in the movement, Mohan Baidya “Kiran,” also separated from the Prachanda group. “Baburam won ideologically in 2005-6—Kiran said to me when we met in his modest home just north of Kathmandu—but not organizationally.” He means that Baburam’s ideas about compromise won out in late 2005, but it was Prachanda-without-Baburam-having-much-say who went on directing the party. This goes a long way toward explaining how the party’s leadership was not sufficiently forthcoming about there being a compromise, with all the consequences that go with it.

An important lesson! The ideas that win out in a movement should also be implemented with clarity and with all their consequences. If they are wrong, then at least we will learn from the results. Yet saying one thing and doing another, or doing a thing and not saying it… all of this is frankly toxic to a revolutionary movement, because one loses one’s bearings and cannot even learn from one’s errors. Independently of whether reason was on the side of Baburam (who wanted to compromise) or Kiran (who was against it), there was no chance to test their respective hypotheses in the party, because they were not put in practice explicitly and with all their consequences (making serious evaluation impossible). Practice may be the ultimate test of revolutionary truth—as Marxists from Lenin to Mao have often maintained—but the testing process must be done with the awareness and participation of the movement’s members.

This kind of problem has also wreaked havoc in revolutionary Latin America. The many compromises in post-Chávez Venezuela (they happened before his death, but the real pressure to compromise came afterwards) were usually never acknowledged. If acknowledged, it was barely so. (The Cubans, it should be said, have done better with their recent concessions, since despite the discourse about “perfecting the revolution,” they usually don’t claim that the current opening to capitalism is anything but a tactical necessity.) The crux of the issue is transparency with your followers. How can you rally from a tactical retreat and move forward, if you claim to already be in an advanced position? How is it possible to recover lost ground, if your official line is that it was never lost? Mayhem occurs when a compromise or defeat is simply baptized as a victory.

Transparency is not a sentimental idea, nor is it merely an idea. Since a revolutionary movement depends—much more than a reformist one—on the conscious action of the masses, then denying the masses a correct and clear view of things has disastrous consequences. Of course, you shouldn’t allow your discourse to play into the enemy’s hands, but what is it that the imperialist enemy does not know already in these days of sophisticated cyber-surveillance? Moreover, what more could the enemy’s mass media say to stain the world’s few remaining revolutions? In fact, everything damaging has been said and will be said, true or not.

This brings us back to the relation between the military and the political. A military defeat cannot be turned magically into a political victory. This much follows from Clausewitz’s claim that war and politics form part of a continuity. From their position of relative power, Nepal’s Maoists of the Prachanda tendency should maintain clarity and consistently communicate the limited nature of their victory. Likewise the leaders of actually-existing Chavismo, who have impressively maintained control over the state during the last five years, have achieved important feats but very incomplete ones. Both leadership groups have successfully avoided worst-case scenarios—such as loss of state power or invasion—but along the way they have made huge concessions and compromises.

The burning question in each context is: Can these concessions be successfully navigated and later rolled back by the revolutionary movement? Military and political advances can, of course, follow on military and political setbacks. Yet this transformation is never an alchemical process, a mere passage from one sphere to the other. Only concrete struggle can transform any kind of defeat into any kind of victory.

A famous Maoist slogan is: Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun. With the crisp clarity that should be the mark of all revolutionary slogans, the lemma continues to be relevant despite the Left’s current electoral fetishism. But the reference to a gun and barrel in the slogan should remind us that a force is only as good as its orientation: The political power born from the mouth of a gun needs to maintain aim and direction, and this requires careful guidance. Communicating that orientation to everybody in the movement—which was done with such skill by Pasang during the battles of the People’s War—is one of the key challenges of the embattled Left today, not just in Nepal, but all around the globe.