Recently, news reports in US and European newspapers have suggested that Washington and London are considering a major reduction in their forces in Iraq. These reports usually fail to mention that those same forces were increased only last summer and that the rumored reduction is really not as large as advertised if you look at the actual numbers in country. Also, with few exceptions, most of these reports don’t bother to state that if the troops are pulled back from the front and brought home, the Pentagon plans to replace their combat capability with air power. For those who were around during the US war in Vietnam, this plan is an eery echo of the last few years of that war. Back then, this strategy was part of the Nixon administration’s plan for “peace with honor.” It was a plan known as Vietnamization and worked like this: South Vietnamese troops (ARVN) worked with diminished US forces on the ground, attacking guerrilla forces and their supporters after calling in air strikes conducted by US Air Force (USAF) planes. In addition, there would be occasional bombing campaigns that targeted entire areas of the Vietnamese countryside and lasted for days or even weeks, destroying whole villages and parts of cities and killing civilians by the hundreds. Perhaps the best known of these massive bombing campaigns took place during the month of December in 1972 and were known as the Christmas bombings. This storm of death was the biggest campaign of its kind and destroyed portions of Hanoi and many other northern Vietnamese cities. More than 1,600 Vietnamese died in that eleven day period.

At this point, it seems that the US is using its air power in Iraq (and Afghanistan) for what they call close-support operations. Usually this means that the air attacks are on a relatively small scale and that bombs and rockets are targeted at individual buildings and city blocks. Still, the number of air support missions is not small. In fact, according to a November 28, 2005 press release from the U.S. Central Command Air Forces, “Coalition aircraft flew 46 close-air support missions Nov. 27 for Operation Iraqi Freedom. They (the missions) supported coalition troops, infrastructure protection, reconstruction activities, and operations to deter and disrupt terrorist activities. Coalition aircraft also supported Iraqi and coalition ground forces operations to create a secure environment for upcoming December parliamentary elections.” These 46 missions were followed by 42 more on November 28th. That’s 88 acknowledged air support missions in two days. (In addition, 18 more close support missions were reported in Afghanistan for the 28th of November). Multiply that by seven days in a week, and it becomes 308 flight combat permissions in Iraq alone.

Given the nature of the weaponry, even so-called close air support means that there will be civilian deaths. It’s pretty much impossible to kill only one or two people with a quarter-ton bomb or even a 50 pound rocket. The collateral effects of the use of such rockets by Israel on cars motored by Palestinian resistance members proves this point quite graphically. The old film of Vietnamese farmers raked by gunfire from US attack copters and rockets from low-flying US jets underline the likelihood of increased civilan dead, as well.

So, why then are the Pentagon and White House considering this change in strategy? Plain and simple, it’s about US domestic politics. Back in 1969, when Nixon was elected to his first term, he promised to bring peace with honor and end the war in Vietnam. Instead, he expanded the war and it became even bloodier. At the same time, however, he did begin to remove US troops from ground battle.

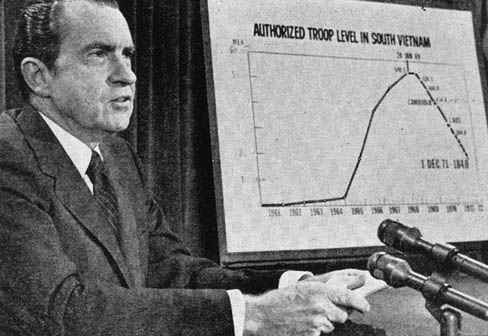

Richard Nixon Announcing Projected US Troop Withdrawls

Since the ARVN was not trusted by US commanders to carry out the war on its own, the Pentagon used the remaining several thousand US ground forces to lead search-and-destroy missions with the assistance of USAF weaponry and the ARVN. Although this strategy made the war planners in Washington look good to the war-weary US public while they conitnued the killing of Vietnamese, it did not sit so well with the Saigon government. They knew it would not keep them in power. Robert H. Johnson, a member of the Policy Planning Council in the US State Department from 1962-67, wrote in the establishment journal Foreign Affairs in 1970: “It is evident from (South Vietnamese) President Thieu’s cautious views as to the appropriate timing of U.S. withdrawals, as well as from the continuing flow of news reports on the views of American officers in South Vietnam, that many in Vietnam — aware of the persistent, long-standing weaknesses of the ARVN’s military efforts — are rather less sanguine than U.S. policy-makers about the prospects for a reasonably early U.S. pullout” (“Vietnamization: Can It Work?,” July 1970).

Despite this, there was still some talk from the warmakers’ circles in July 1970 that the US could achieve its goals in Vietnam through military action from the air, even as it was removing its ground troops from Cambodia after the violent and widespread opposition to the April 30, 1970 invasion of that country. To illustrate this, even though US troops were for the most part removed from Cambodia, the bombing of that country continued unabated until the US-installed government fell to the Khmer Rouge in spring 1975.

Back to Iraq. There is still a committed belief in the Bush White House and much of Congress that the US can achieve its goals militarily in that country. This is apparent in the words of the White House and in the supposedly more moderate words of Democrats like Joseph Biden (Del.). The White House and the vast majority of Congress do not differ on the war, only on how it is being conducted. One can bet their holiday dinner that the majority of Congress would love to see US air power doing most of the killing and destruction in Iraq. This shift in strategy combined with a redeployment of US ground forces to Kuwait and well-fortified defensive positions in Iraq would probably decrease the number of US casualties and (they hope) ensure the re-election of most of those congressmen and women who will hear the wrath of their constituents when they go home for the winter holidays in a few weeks.

According to a Seymour Hersh piece in The New Yorker on November 28, 2005, some USAF commanders are concerned about switching to the greater use of air power in Iraq. The two primary reasons they mention are the increased danger of civilian casualties and the possibility of Iraqi commanders calling in the strikes. The former concern, while noble, is increasingly pointless, given the nature of the war on the ground, where the occupying forces tend to shoot first and determine the nature of their victims later. Unsaid in these officers’ concern is the historical fact that air power doesn’t work against a guerrilla insurgency. If it did, then wouldn’t Ho Chi Minh City still be named Saigon? Would the FARC guerrilla forces in Colombia still control a substantial portion of the Colombian countryside? It seems that air power does not win wars — it only destroys the earth and makes a lot of money for the weapons industry. That, and it increases the hatred of the population that the aircraft and their pilots are bombing Perhaps if an aggressor is willing to carry such a policy to its logical conclusion — total devastation — then that aggressor can probably win its war, albeit there will be little left to win (except for that oil in the case of Iraq). Is this what George Bush means when he insists on nothing short of victory? If not, then it seems that the only reason for a strategy that replaces ground combat with death from the air is some kind of chauvinistic revenge.

Ron Jacobs is author of The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground, just republished by Verso. Jacobs’ essay on Big Bill Broonzy is featured in CounterPunch‘s new collection on music, art and sex: Serpents in the Garden. He can be reached at <[email protected]>.