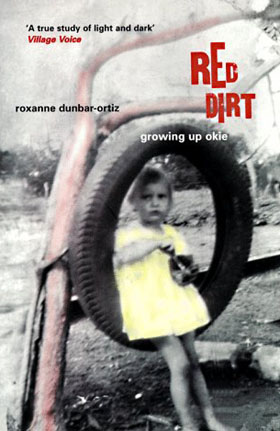

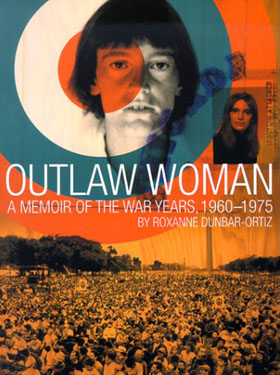

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz is no armchair theorist. She was and is on the front lines of struggles for social justice at home and abroad. An acclaimed author, Dunbar-Ortiz is also a professor of ethnic studies at California State University, Hayward. Her substantial body of work includes Blood on the Border: A Memoir of the Contra War (South End Press, 2005), Outlaw Woman: A Memoir of the War Years, 1960-1975 (City Lights Books, 2001) and Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie (Verso, 1997).

Seth Sandronsky: You were born and reared in Oklahoma. How has your sense of that place shaped you and your writing?

Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz: I left Oklahoma in January 1960. At the time, it felt like an escape from prison, or at least claustrophobia. Although I was raised a fundamentalist Protestant as a Southern Baptist, thanks to my agnostic boyfriend whom I married at age eighteen, I had rejected fundamentalism, then Christianity altogether, and after a couple of years in San Francisco realized I had become an atheist. But, during the last three years in Oklahoma, I had become acutely aware of the ignorance induced by fundamentalism, which was so integrally tied to blind patriotism — “my country right or wrong” — that I felt desperate to escape it. The other cultural aspect driving me crazy was the widespread, vicious racism. The civil rights movement in the South had been top news in Oklahoma since the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown decision ordering the desegregation of public schools, not news reporting, but slanderous attacks on the movement, tying it with the “plague of communism.” This latter, anti-communism, was another element of my sense of imprisonment. Then there was the personal, most notably my alcoholic and often violent mother.

Leaving Oklahoma felt like liberation; San Francisco, my new home, felt like a foreign country, just what I longed for. I regarded myself as a political exile, and never came to consider any other place “home.” Most of my new friends were foreign nationals. I disciplined myself never to be nostalgic or even think of Oklahoma. During the following decade, I returned to Oklahoma for brief visits only three times, and each time could not wait to get out. In the 1970s, I got better about visiting my father after my mother’s death, but with that same sense of having to escape as soon as possible.

As I relate in my book, Blood on the Border: A Memoir of the Contra War, memories and aching love for Oklahoma overcame me on my first visit to northeastern Nicaragua (Miskitia) in May 1981. By then, I had a doctorate in History and had published or edited four scholarly books and many articles. I considered myself an activist and a historian. Writing was the culmination of research, not a passion or an art for me. That changed. I finished another scholarly book that was published in 1984, but, after that, I began writing stories, some fictional, most non-fiction, my perceptions of the Miskitia and its people, the majority of whom are the indigenous Miskitu. Everything about the place and the people reminded me of Oklahoma –inundated with US fundamentalist Protestant missionaries spreading ignorance and anti-communism, the poverty, the racism, even red earth as in Oklahoma. The US Marines had occupied the zone in the 1920s, to protect the US owned businesses, particularly Standard Fruit Company (bananas and pine forests) and had introduced country and western music, which was still the favored music of the region during the 1980s, and had been the music of my childhood in rural Oklahoma. I could not help but come to the conclusion that if the Sandinistas recognized the humanity of these people and this place, the Miskitia, why could I not respect my own family and the people I grew up with. I realized how much I missed the land itself. The next time I went to Oklahoma, in 1986, I saw with my childhood eyes the beauty of the land, the smells and sounds. I saw the humanity in the people.

In 1989, I began a book on the Miskitia and the US sponsored contra war waged there, writing in a way I never had before, with passion, but I kept straying from the story to another one, to Oklahoma and its people, my grandfather who was in the Industrial Workers of the World in the early part of the 20th century, the systematic terror unleashed to impose fundamentalism and anti- communism. Finally, I put aside the Miskitia and wrote what was published in 1997: Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie.

SS: Racism and sexism are to capitalism what air is to people. Please talk about your work on the intersections of capital, gender, and race during the past 30 years in the U.S.

RDO: Class, race, and gender have marked my life since I was born poor, female, and part Indian, and class, race, and gender have been central to my political consciousness for the past forty years as an activist. Class consciousness came early for me. My father hated rich people, a kind of roughhewn class perspective inherited from his own father who had been a member of the Industrial Workers of the World in Oklahoma; my grandfather named my father, who was born in 1907, Moyer Haywood Scarberry Pettibone Dunbar. The IWW was brutally crushed in Oklahoma, leaving fear and bitterness in working people like my father. He passed on to me his hatred for the rich and mistrust of government (the IWW was crushed by federal and state authorities, and their death squad, the Ku Klux Klan). I was acutely aware of the unfairness of poverty with only the wealthy few controlled everything.

I was fortunate to have come of age during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s; otherwise I fear that I would not have become conscious of racism and the courage of those resisting it. My brother and sister, who were ten and eleven years older than I, did not rejoice as I did in the struggle against racism. All of us were aware of the outsider status of our mother — an orphan whose mother had been Indian — in the white rural community where we grew up, but we had no word for it or way of understanding white supremacy, and my mother pretended it wasn’t happening, trying so hard to be accepted.

I had no notion at all of being discriminated against or of the limitations I faced as a female, until I was in graduate school in History at UCLA. I had been introduced to Marxism a bit before I left Oklahoma and was obsessed with reading about the Russian Revolution, but I didn’t identify myself as a Marxist until I got involved in 1965 with an anti-apartheid group, started by two South African political exiles, at UCLA. I was also passionately involved in antiwar organizing, graduate student union organizing, and civil rights. Not only in the History, as one of six women out of 50 or so doctoral students, but also in my activist life, I became aware of male supremacism. I became extremely angry and determined to fight it. In early 1968, I left graduate school, burning bridges, and moved to Boston to organize women.

I found other women doing the same thing, organizing for women’s liberation, and in the fall of 1968, we organized the first national conference of the women’s liberation movement. I moved to New Orleans in late 1969 to organize women in the South, got increasingly involved with anti-racist and antiwar work. After two years in the South, I returned to California and was recruited to the American Indian Movement soon after the siege at Wounded Knee in 1973. This, in turn, led to helping organize an emerging international indigenous movement and lobbying at the United Nations.

SS: The U.S. right wing is on a roll after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. What are your thoughts on the prospects for progressive American politics in 2006?

RDO: That’s a tricky question. I think it’s somewhat an illusion that the right wing is on a roll, because the United States has been the essence of capitalism and imperialism from its founding. Rather, the bold actions of the Bush administration since 911 have revealed just how weak civil society opposition is in this country. In fact, perhaps it is an illusion to look back and think that our opposition movements were once as effective as we assumed in forcing reform. Liberal capitalism/imperialism, if it constantly reforms itself, remains resilient and doesn’t degenerate into fascism. Now called “globalization,” imperialism is inherent in capitalism’s existence. Not that every capitalist country has to itself be actively imperialistic, but they can remain successfully capitalist only if they are in the capitalist bloc, now and since the mid-20th century, singularly led by the United States. The collapse of the center of socialism — the Soviet Union — took the air out of US movements against capitalism and imperialism, which means that they were “paper tigers” to begin with.

I think we must face hard realities in order to build a movement that puts a stop to the United States. That’s what Blood on the Border is about: in the last surge of opposition to US imperialism, the blatant interventions by the Reagan administration in Central America, we failed. And in that other focus of intervention, in Afghanistan, we paid little attention, and the Soviet Union was crushed. Few in US movements were supportive of the Soviet Union, but whether they were or not, and like it or not, the US-USSR struggle was the context within which our movements operated for seventy crucial years.

I am not being nostalgic for the Cold War — rather, I’m saying that we have to build a revolutionary movement from scratch. I think the younger generation that came of age during the 1990s were beginning to do that with their focus on “globalization,” but without the necessary theoretical framework for understanding the roots and continuity of capitalism/imperialism. That movement was rudely interrupted by 911. Resisting US wars of aggression became imperative.

More than anything, illusions are mind-numbing, and nothing is more mind-numbing than the prevalent idea that the United States was founded as a democracy and has recently lost its way. It was founded as a capitalist state dependent on acquisition of territory to survive. All the rest is history.

SS: Like Marx, you emphasize the role of radical theory in helping the laboring class to liberate itself from capitalist imperialism. With this framework, how do you view the U.S. peace movement?

RDO: The U.S. peace movement today is far more active and widespread than it has been during the past 25 years. Traveling around the country in what are called “red states,” I find strong and growing local peace activities. The 1990s youth movement that challenged “globalization” morphed into antiwar work after the invasion of Iraq. I think many activists and others who criticize the peace movement are really not aware of what’s happening in the vast interior of the United States. Each time I have gone home to Oklahoma in the past three years, I have left so energized by local activism.

As for the viability of a peace movement, it’s quite limited if it does not serve as an organizing base for a broader (and deeper) movement/coalition to bring about fundamental economic, political, and social transformation, starting with the linkage between the war and U.S. militarism/imperialism and its integration with existing capitalism. We very much need something like the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) “travelers” that existed during the first years of the Vietnam War to provide the ideological and geographical linkages needed. Many of us, individually like myself, or organizationally, like Global Exchange and others, do travel and do make those connections, but really have no capacity for leaving something behind, like a chapter of a larger organizations. On the other hand, I think it’s good for local groups to build their own movements without too much intervention or interference from national organizations.

SS: With help from U.S. bankruptcy courts, corporations are liquidating the jobs and retirements of labor union members. What are your thoughts on strategies to resist this onslaught?

RDO: Indeed. The Bush administration’s project of creating what he calls an “ownership society” has been more successful than anything else it’s attempted, and that’s why Bush retains such strong support from the wealthy and aspiring wealthy. We can expect more of the same. The campaign to privatize Social Security has abated, temporarily, but it already has had the effect of creating a kind of passive acceptance, rather than resistance, by those under 50 years old that they cannot rely on it in their future. The Medicare drug benefit was blatantly designed by the administration to bring even greater profits to Big Pharma. And few people seem to even imagine universal health care these days. But, the liquidation of retirement programs for union members by some of the biggest corporations is surging ahead, with untold misery in its wake. This is a breach of contract beyond audacity, and with hardly an outcry.

The early January explosion and tragic deaths of 12 miners at the non-union Sago Mine in West Virginia illustrated the sorry state of U.S. vulture capitalism, attitudes toward unions and workers rights, as well as federal and state negligence. I watched the news obsessively waiting for the appearance of a union spokesperson to condemn the situation, but none appeared, nor was the fact that the mine was non-union mentioned.

In those circumstances, how do we begin to develop strategies to resist? The implosion of both the Democratic Party and labor unions should be seen, I think, as reflecting the ineffectiveness of social movements in the United States at least since the late 1970s when the “Reagan Revolution” came to power. In general, politicians don’t stick their necks out without a social movement pressuring them; in such circumstances, we saw even the most racist segregationists change their tune after a decade of the Civil Rights struggle, or take the actions of Franklin Roosevelt under pressure by a huge union movement. So, the question I think we must ask is how we will build a massive social movement in this country.

I don’t have the answer any more than anyone else at this time, but I do think we are in different circumstances than in the past and can not simply try to repeat what may have worked in the past. And we can no longer separate domestic policy from foreign policy. They have always been symbiotic in the United States, it being capitalist and imperialist, but now we can no longer live under illusions. Nor can we escape United States history, that this is a settler state built on the bedrock of white supremacy. Pessimism is toxic, optimism is foolish, and the truth is liberating.

| Jan. 5 | San Francisco, CA |

San Francisco Main Library, Latino Reading Room 7 PM |

CONTACT: Michelle Tea |

| Jan. 17 | Capitola, CA |

Capitola Book Cafe 7 PM |

CONTACT: 831-462-4415 |

| Jan. 19 | Sacramento, CA |

Marxist School 7 PM |

CONTACT: [email protected] |

| Jan. 22 | Berkeley, CA |

Berkeley Unitarian Universalist Hall 6 PM (Reception) / 7 PM (Reading) |

CONTACT: Cynthia Johnson, 510-525-0302 |

| Jan. 26 | Toledo, OH |

University of Toledo 7:30 PM |

CONTACT: [email protected] |

| Jan. 27 | Ann Arbor, MI |

The Planet 7 PM |

CONTACT Eric Linge |

| Jan. 29 | Madison, WI |

Rainbow Bookstore 7 PM |

CONTACT: Allen Ruff |

| Jan. 30 | Chicago, IL |

Seminary Co-op Bookstore, University of Chicago 7 PM |

CONTACT: Peter Handel |

| Jan. 31 | Chicago, IL |

Heartland Cafe 7 PM |

CONTACT: Brettly, 773-465-8005 |

| Feb. 10 | Houston, TX |

University of Houston 1 PM |

CONTACT: Susan Kellogg |

| Feb. 15 | Lawrence, KS |

Kansas Room of the Kansas Union, University of Kansas 7:30 PM |

CONTACT: [email protected] |

| Feb. 16 | Austin, TX |

Monkeywrench Books 8 PM |

CONTACT: [email protected] |

| Feb. 19 | Austin, TX |

Resistencia Bookstore 2 PM |

CONTACT |

| Mar. 2 | Seattle, WA |

Contact Peter for Time and Place | CONTACT: Peter Handel |

| Mar. 3 | Bellingham, WA |

Village Books 7 PM |

CONTACT: Peter Handel |

| Mar. 14 | New York, NY |

Bluestockings 7 PM |

CONTACT: [email protected] |

| Mar. 16 | Philadelphia, PA |

Home of Our Own 7 PM |

CONTACT: [email protected] |

| Apr. 3-4 | Atlanta, GA |

Georgia State University | CONTACT: [email protected] |

| Apr. 28 | La Jolla, CA |

DG Wills Books 7 PM |

CONTACT: [email protected] |

| Apr. 29-30 | Los Angeles, CA |

Los Angeles Times Festival of Books, UCLA Campus | CONTACT: Kristina Erbstoesser |

| May 3 | Los Angeles, CA |

Skylight Books 7 PM |

CONTACT: [email protected] |

Seth Sandronsky is a member of Sacramento Area Peace Action and a co-editor of Because People Matter, Sacramento’s progressive paper. He can be reached at <[email protected]>.

Seth Sandronsky is a member of Sacramento Area Peace Action and a co-editor of Because People Matter, Sacramento’s progressive paper. He can be reached at <[email protected]>.