It is fascinating for me to think about SDS. In fact, it’s downright compulsory. I am gathering stories and pictures, trying to weave them into a script for an artist to make into a visual (or comic-book) history, mostly “from the bottom up,” i.e., the chapter standpoint. Sometimes the national leaders were good, sometimes they were terrible, but what happened at the base is the vital story, from the historic moment when SDS became a real social movement.

Why SDS then? The arguments are familiar and I won’t try to rehearse all of them. The Empire had pushed ever onward and — as I encountered SDS in the flesh for the first time — had badly overextended itself in Vietnam. The Old Left had come to a standstill. Liberalism had flopped and had become part of the war machine — or rather had always been part of the war machine. It could be pulled leftward but not far. Certainly not by young people joining the Campus Democrats, hoping to become powerful politicians and speechwriters someday. To do anything good at all, the Democrats needed a fire to be set under them. And a larger vision to be set out independently, something vastly beyond their compromised and bureaucratic grasp.

Of course, the Port Huron Statement was already on hand, and a splendid document it was. I got my fifty cent copy of the booklet from the same table where I paid my $5 membership and got my card. I was already a Marxist of some sort. But I could see that the PHS offered a vision in a new key, much as Paul Potter had called upon us to “name the system” in the previous spring’s Washington demonstration that put SDS on the map.

SDS outstripped the other leftwing organizations on campus and also abandoned its social democratic roots because it presented the empowerment of students IN THEIR OWN NAME, urged them forward, gave them watchwords, rather than directing them only outward, to constituencies off campus. It had never been done effectively before, and has not been done effectively since.

So, why now? The reasons should be pretty obvious. The empire has overextended itself again. The Democrats have never changed much (and, for the most part, didn’t really want those idealists brought in with George McGovern and afterward — at least not to challenge the basic tenets and power centers), certainly not at the top. If individuals can sometimes be brought over to useful positions, on various issues, it will happen only through building a movement not dependent upon them.

So, why now? The reasons should be pretty obvious. The empire has overextended itself again. The Democrats have never changed much (and, for the most part, didn’t really want those idealists brought in with George McGovern and afterward — at least not to challenge the basic tenets and power centers), certainly not at the top. If individuals can sometimes be brought over to useful positions, on various issues, it will happen only through building a movement not dependent upon them.

That movement has advantages now that none has had since the sixties, and not only in the fact of imperial overreach. To take an obvious example, the movements in Central America of the eighties were drowned in blood, but the new movements percolating out from Venezuela will not so easily be overwhelmed. Nor has the US economy been up to its eyeballs in global debt until our current era.

There are a thousand things going against the prospects of a successful new SDS, of course. Administrators and the majority of professors won’t like the new SDSers very much, because “business as usual” is more comfortable and more corporate-friendly. Various existing leftwing organizations will probably resent the competition and gripe, or infiltrate. (No statutory standard can keep them from doing so, in my view, and all efforts to restrict membership will be counterproductive.)

But this is the time. The vacuum is there. The imperial crisis is escalating, without any sign of resolution. Most important, millions of college students have no particular political orientation and little understanding. Some of the best, most effective SDSers grew up as young Republicans, anti-staters who might have been called “libertarians” if the word had been popular, young people from Texas, Oklahoma, rural parts of the Midwest . . . and, of course, joined with them, the descendents of Jewish (as well as other) leftwingers from generations past. Experiences of every background counted. And today, students of all backgrounds can be shown the need to mobilize, to help prevent the ongoing devastation of our world, to help empower the lowly as students learn to empower themselves, and to set out a vision of a really democratic society.

There’s the key. The Industrial Workers of the World had it long before. Decentralized democracy, democratic decision-making at all levels, is the most radical idea ever hatched in North America and the only one with real lasting appeal. It makes sense to demand more democracy on campus, including transparency of where the money comes from and what the corporations or government agencies get in return. It makes sense to resist the re-militarization of campus. It makes sense to reach out to a multitude of others, including antiwar GIs, who come from a different place but share a lot of resentments and positive values.

But students need to speak for themselves, their generation, the world they are already inhabiting and will continue to inhabit. That’s the vision that made SDS great and made it most useful to liberation movements elsewhere on earth. With a great deal of cooperation and energetic effort from students of all kinds, SDS can become great again. Building it, growing personally while sharing the project with old friends and those not discovered yet, can be the most rewarding experience imaginable.

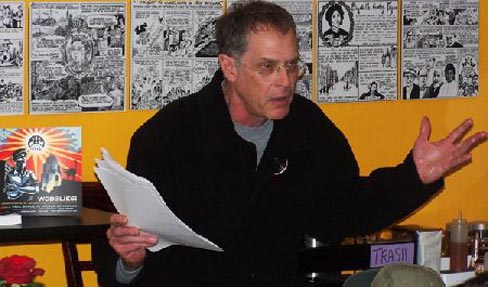

Founder and publisher of Radical America, Paul Buhle was active in Champaign-Urbana, Storrs, and Madison SDS chapters, 1965-1969. He hasn’t been all that happy since, but he teaches at Brown. A founding member of the new Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), Buhle sees the struggle for Participatory Democracy as essential for peace and progress. For more about SDS today, visit www.studentsforademocraticsociety.org. This essay was adapted from one published in Next Left Notes. [Next Left Notes

(c) 2004, 2006, Thomas Good.

Verbatim copying and distribution of the entire article is permitted without royalty in any medium provided this notice is preserved.]