Click on the image to watch a preview of “Soldiers & Students”

|

One of the largest youth antiwar organizations — the Campus Antiwar Network — is calling for a week of actions against military recruitment on March 13-19, 2006. Pepperspray Productions of Seattle recently released a DVD titled “Soldiers & Students” that features counter-recruitment actions and interviews with veterans opposed to the US imperial military. Condi Rice and the rest of the Bush gang (with a good deal of help from the so-called Democratic opposition) are ratcheting up military threats against Iran and at the same time trying to figure out how to keep their bloody fingers in Iraq and Afghanistan. Antiwar coalitions are planning for national actions against the war in Iraq and the threat of more war in Iran. Knowing many of the young people who are involved with the campus antiwar groups (and many more who aren’t), I recently found a little time to reflect on my personal journey towards antiwar protest.

Some time in spring 1968 was when I knew for sure the Vietnam war was wrong. Some time in spring 1968 was also when my dad knew he would have to go there. The murders of Martin Luther King and Bobby Kennedy, and the police riots in Chicago, convinced me that it might be more than just the war that was the problem.

Before my dad went off to the war, he went to some schools in Virginia for extra training. One was called the Armed Forces Staff College and I was not really sure what he was learning there. The other, however, was called the Air War College. There was little doubt as to what they were teaching him at that institution. While he was there, the Soviet army invaded Prague and quelled a rebellion there. A couple weeks later, the police beat young people in the streets of Chicago. Dad headed off to Vietnam in the winter of 1969 and I copped my stance. There was no way that I was going to be the military version of John Fogerty’s fortunate son.

|

As summer ended and I prepared myself for high school, the antiwar movement started creeping into our small suburban town not more than fifteen miles from an Army post. One of my friend’s older brothers used to give me movement literature he picked up at college and distributed at the shopping center in the Maryland town we lived in. The first poster I remember was one that had a picture of Nixon that said “Would you buy a used war from this man? PEACE NOW.” I used to go over to their house to listen to records and drink beer on the sly. A lot of the stuff I read didn’t make a whole lot of sense to me, but the basic message that we didn’t belong in Vietnam killing people did.

I also picked up some pamphlets at a Who concert some friends and I ended up on the outskirts of while we were on a Boy Scout trip that never reached its destination due to the concert traffic. We were four teenage scouts who knew that our scouting life was almost over. I was having a hard time with the blind patriotism the organization insisted on, and my friends were turning their interests to the world of girls and music. However, we still liked to camp out and were just a little afraid to tell our dads that the scouting life was over. So we played along, pretending to our parents that we were good scouts and at the same time always looking for a way to turn our scouting trips into something more interesting. So when we came upon the ten-mile traffic jam on Route 29 going towards Columbia, Maryland, we were quite curious. There were longhaired young people walking along the road, hanging out of car windows, flashing peace signs, and (as I found out a year later when I was handed a joint while listening to a street singer in a subway station in Frankfurt) smoking pot. One of my friends reminded us that there was a Who concert that evening, and the four of us in the car decided that the concert sounded much more interesting than the swimming trip we were planning to take. So we moved into the flow of traffic and ended up in the parking lot of the concert site. Although we did not have tickets, we stayed on the fringes of the crowd and listened to the band. The Woodstock festival had occurred only days before, and we wanted to be part of the newly formed Woodstock Nation.

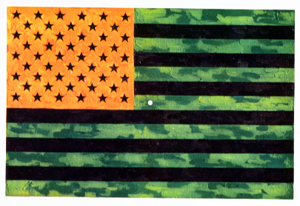

Jasper Johns, “Moratorium,” 1969 |

School started in September, and some of the kids who lived closer to DC were working on the big demonstration coming up on October 15 — the Moratorium. A few of the nuns agreed with their efforts and got the school to hold a small meeting of its own. The first person who talked was an Army guy who said the usual Army stuff. Then a pacifist priest spoke. After the two talks and some discussion, those of us who wanted to walked to downtown Laurel and joined the small antiwar vigil taking place there. I don’t remember if there were any hecklers, but there were around fifty of us against the war.

The next big demonstration was a month later in D.C. A friend from school and I planned to take a Greyhound bus into Washington, D.C. without telling our parents. We figured we would be back by dark. Unfortunately, while we waited outside the bus station in Laurel, his mom drove by. She saw us and stopped to ask us where we thought we were going. Neither of us could come up with a good lie, so we told her the truth. She didn’t get mad but insisted we get in her car. After a brief argument, we did as she asked. I settled for listening to a live broadcast of the day’s protest on the radio and reading about it in the papers.

Over the next five or six years, especially after our family moved to Germany, I spent a good deal of my time writing in high school underground papers against the war and going to demonstrations. As the war went on and on, my analysis became more and more radical. By the time of the demonstrations in Germany supporting the Mayday 1971 demonstrations in the U.S., I was calling myself an anti-imperialist. At a demonstration I attended following May after the Weather Underground had bombed the Pentagon, I fell in behind a group of German youth shouting “Für den sieg des Viet Cong, Bomben auf das Pentagon.” It was at this demonstration that I saw police use a water cannon for the first time, too. A small woman not more than twenty feet away from me was knocked down and pushed across the cobblestones a good seventy-five feet. When the medics reached her, the seat of her jeans was torn away and her buttocks were bleeding. The war ended three years later. The bleeding continues.

Ron Jacobs is author of The Way the Wind Blew: A History of the Weather Underground, just republished by Verso. Jacobs’ essay on Big Bill Broonzy is featured in CounterPunch‘s new collection on music, art and sex: Serpents in the Garden. He can be reached at <[email protected]>.