Susette Kelo (Photo by Isaac Reese, 2004 / © Institute for Justice) |

“Justices OK land grabs!” “Property rights under attack!” “No homeowner safe from government!” “The sky is falling!” So argued critics from across the political spectrum in response to a 2005 U.S. Supreme Court ruling upholding a municipality’s use of eminent domain power to take possession of private property and sell it to private developers (Kelo, et. al v New London). Much of the outrage stems from a sense that the High Court has stooped to a new low in its failure to limit government power and protect individual rights. Meanwhile, opposition to the court’s decision has aligned traditional political adversaries: civil rights organizations and social justice groups with free market think tanks and small business associations. According to the libertarian legal foundation Institute for Justice, the ruling has pushed more than forty state legislatures to consider eminent domain reform. But the irony of a dissenting Clarence Thomas’ newfound concern for the plight of poor communities notwithstanding, Kelo upholds — rather than demolishes — the keystone that has historically shaped U.S. politics: private power over public policy.

The concept of eminent domain was interpreted narrowly in the United States until the second half of the twentieth century. Prior to that time, constitutional interpretation of the Fifth Amendment “takings clause” — the first provision of the Bill of Rights to be incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment and made applicable to the states in 1890 — limited government’s exercise of this power to the likes of building roads, waterways, schools, and utilities. According to the amendment, private property can be taken for “public use” with “just compensation.” Restricting “takings” to such projects did not, however, denude governments of the authority to carry out controversial planning schemes and implement vast infrastructural development policies. “Grand Master Planner” Robert Moses wiping out entire New York City neighborhoods standing in his way is the best known example.

Not until Berman v Parker (1954) did the Supreme Court begin to construe the phrase “public use” to mean “public purpose.” While detractors cite William O. Douglas‘ opinion — on behalf of a unanimous court — upholding redevelopment of a Washington, D.C. “blighted area” as an example of modern-era “judicial lawmaking,” the decision actually deferred to the legislature’s constitutional authority to makes laws. As for those who advocate judicial “original intent” (referred to as “initial understanding” by some), the framers left little evidence as to what they intended by the phrase “public use.” In any event, the aftermath of Berman witnessed local governments invoking eminent domain to make space for sports stadiums, convention centers, and shopping malls. Expanded use of condemnation went hand in hand with “urban renewal” — the program started in 1949 through which local public agencies (LPAs) used federal funds to clear “slums” and resell the land to private developers, who would ostensibly build affordable housing and commercial buildings on the property. Eminent domain made land parcels available that would not otherwise have been available because of recalcitrant property owners unwilling to sell.

Urban renewal forced residents and merchants in redevelopment areas to relocate. Sure, federal regulations required that LPAs provide relocation assistance, but such aid was usually inadequate. Criticism came from various quarters: activists decried the destruction of neighborhoods and communities, black residents denounced what they called “Negro removal” (75% of those displaced were African-American), and market conservatives disapproved of government taking property from one group of private citizens (homeowners and merchants) and turning it over to another (developers). While absence of a “unitary interest” often pitted opponents of urban renewal against one another, local renewal coalitions were held together by powerful economic interests single-minded in their desire to redevelop central business districts (CBDs). Towards this end, “blight” was defined loosely so that it could be applied to robust communities such as Boston’s West End (that area’s leveling has been recounted numerous times) or to maintain segregation as happened in Atlanta where a planning commission report stated that the “wise thing” was to move blacks from neighborhoods deemed “too close” to the downtown commercial area.

Increasing reliance upon eminent domain produced conflict over what constitutes a Fifth Amendment “taking,” the issue eventually occupying a considerable portion of the Supreme Court’s attention. Justices would put aside the notion that “public use” literally means that taken property must be owned and operated by government for open use by the public in Hawaii Housing Authority v Midkiff (1984). In Midkiff, a unanimous Court ruled constitutional a Hawaii legislative land reform act empowering authorities to condemn large holdings (almost 50% of the state’s land was owned by 72 property owners), transfer ownership to tenants, and arrange compensation for those who lost their property. Writing for eight justices (Thurgood Marshall did not participate in the case), Sandra Day O’Connor’s opinion followed Berman in asserting that the matter under consideration was properly legislative and that the role of judicial review here is “an extremely narrow one.” Importantly, this is the premise upon which Kelo was decided; John Paul Stevens, who wrote the five-justice majority opinion in Kelo, stated later that he would have opposed the policy outcome had he been a legislator.

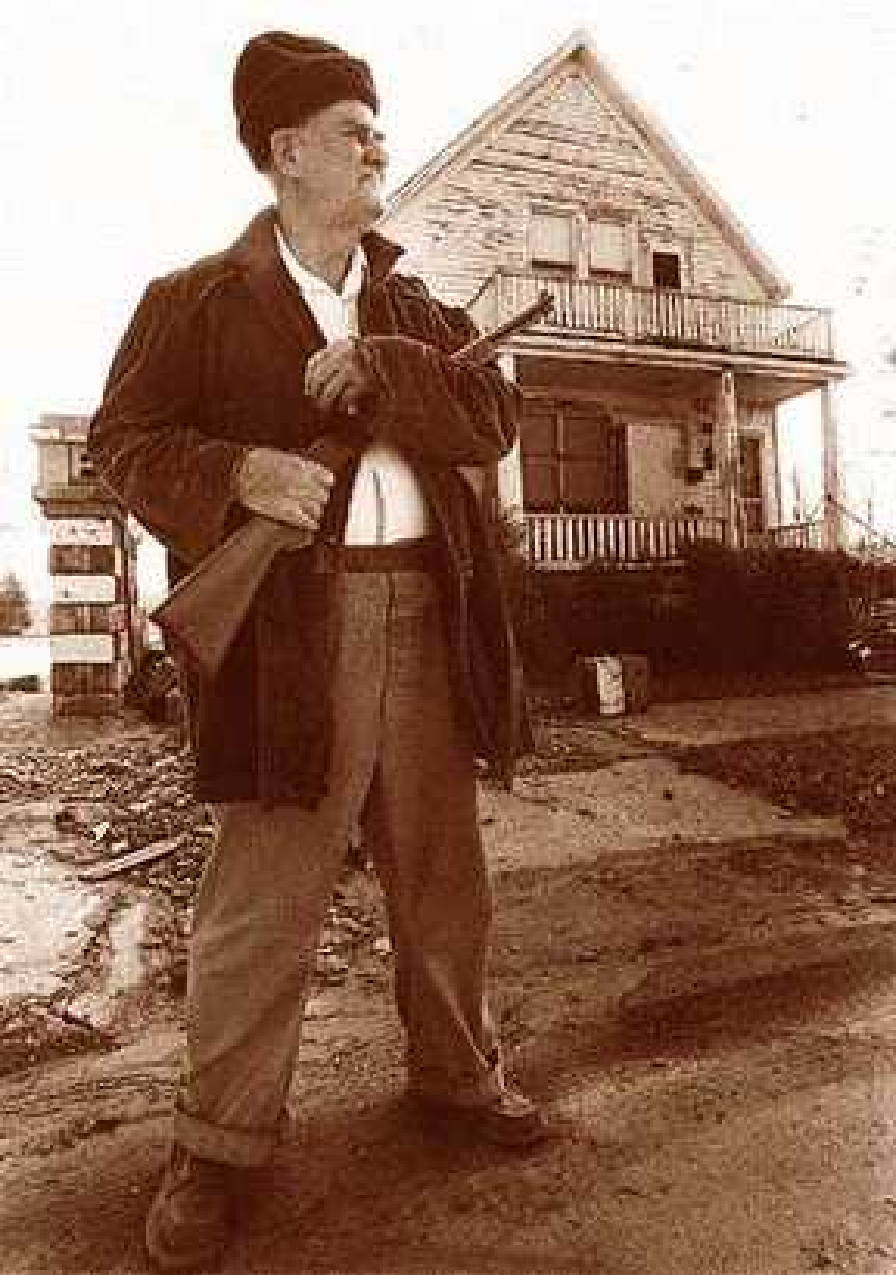

John Saber, one of the last residents of Poletown, stands guard in front of his home (Jenny Nolan, “Auto Plant vs. Neighborhood: The Poletown Battle,” The Detroit News)

|

Less noticed in O’Connor’s Midkiff opinion has been her “populist” assertion that breaking up “land oligopolies” and correcting the “evils associated with . . . concentrated landownership” is justified. Significantly, this appears to be the basis upon which she wrote her “Robin Hood in reverse” dissent in the New London case. Such misgivings aside, the use of eminent domain has almost always resulted in upward redistribution; “community revitalization” occurring at the expense of the housing and livelihoods of the poor, minorities, sole proprietors, and working people (middle-income folks pay as well in the form of higher taxes). The bulldozing of Detroit’s Poletown where several thousand inhabitants were displaced in favor of a General Motors assembly plant and the razing of the area in Manhattan where small local business owners fought unsuccessfully to stop construction of the World Trade Center are among the widely known instances of eviction for “public benefit.” Unfortunately, the removal of African-American, Haitian, and Latino residents and shopkeepers in places like Delray Beach, Florida and elsewhere draws little notice (the Institute for Justice reported 10,000 cases nationwide of what it calls eminent domain “abuse” between 1998 and 2002; of course, characterizing such cases as “abuse” is misleading, in so far as it suggests that they are exceptions rather than the rule).

Condemnation for private development and gain is often the work of “public authorities” possessing the force of government, generally in the form of community redevelopment agencies (CRAs) today. Brainchild of the aforementioned Robert Moses, these quasi-public/semi-autonomous bodies are largely impervious to oversight. While the “rational planning” techniques of professional staff may draw the ire of free-market ideologues, CRA boards (appointed by either mayors or councils) are usually comprised of lawyers, bankers, contractors, developers, accountants, and real estate agents from prestigious local firms. Public hearings are required by law, but these are often perceived to be exercises in futility: charades in which citizens have no clearly defined role to play and lack the time and resources needed to effectively participate. Moreover, opportunities for input are not necessarily forthcoming. In mid-1990s Boston, for example, the redevelopment authority designated City Hall Plaza — itself a product of the urban renewal era — a redevelopment tract and granted the parcel of land to a “public trust” of finance, construction, investment, and real estate concerns, all without citizen comment.

Midkiff‘s “public benefit” premise conceivably lays a legal foundation for the innovative use of eminent domain: specifically, downward property redistribution. Construction of new housing units could be a socialized public service that functions as a fetter on an important source of capital accumulation, rather than a means of subsidizing private profits. Progressive coalitions in certain cities have “linked” condemnation to requirements that developers contribute to trust funds for affordable housing and job training programs. Additionally, a few cities have considered invoking eminent domain to prevent important local employers from “closing up shop” and moving elsewhere. In 1996, New Bedford, Massachusetts fell one city council vote shy of approving a United Electrical Workers proposal to condemn a tool-cutting plant, purchase it, and sell it to a worker-owned firm in order to keep the facility in town and operating.

Terra Company Relocation Agents celebrate “the relocation of 378 residences & businesses on this project in just nine months” on 10 January 2002

|

What exists in most cities, however, are interest coalitions in which pro-growth business elites dominate because they control access to goals that most elected officials seek. In other words, they exercise systemic power over city government. While their power is not always overt, eminent domain in their hands can leave some residents and proprietors “one step ahead of the bulldozer.” While entrepreneurial/corporate regimes, which are primarily interested in downtown development policies, remain in power, reorienting city priorities toward serving low-income residents and/or neighborhoods beyond taking token measures can be next to impossible.

Can public purposes be accomplished by the use of public power for private development? The late Bobby Kennedy, who helped establish the first community development corporation in the United States, thought so, arguing that public-private “partnerships” like that combine “the best of community action with the best of the private enterprise system.” Public-private “partnerships” today, however, are even less public than before, costing the public more for less. Tax abatements are to eminent domain today what urban renewal was to it a half century ago. But if the rationales of tax abatements and urban renewals are essentially the same — i.e., to entice private developers — there exist two important differences: 1) the federal government paid two-thirds of the subsidy under urban renewal, whereas local taxpayers bear the entire brunt of tax abatements; 2) developers had to follow plans approved by federal and local governments under urban renewal, whereas tax abatements generally subject developers to fewer public controls. At best, public-private “partnerships” are attempts to reconcile what Marx called irreconcilables; at worst, well, history speaks for itself.

Michael Hoover is a professor of political science at Seminole Community College. Hoover co-authored City on Fire: Hong Kong Cinema. with Lisa Odham Stokes. Hoover serves on the editorial board of New Political Science, journal of the caucus for a new political science.

Michael Hoover is a professor of political science at Seminole Community College. Hoover co-authored City on Fire: Hong Kong Cinema. with Lisa Odham Stokes. Hoover serves on the editorial board of New Political Science, journal of the caucus for a new political science.