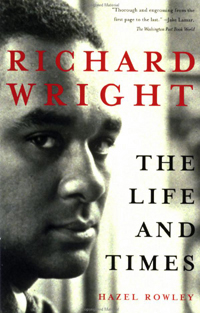

RICHARD WRIGHT: The Life and Times by Hazel Rowley BUY THIS BOOK |

The author Richard Wright, whose works were recently republished by the Library of America, was a hospital orderly making thirteen dollars a week when he first experienced what literary biographers would call an epiphany. It was in Chicago; the year was 1933. The unlikely instrument of Wright’s revelation was a treatise by Joseph Stalin. To a sharecropper’s son vexed by memories of lynching, racial hatred, and segregation, Stalin‘s views on The National and Colonial Question were galvanic. In his memoir American Hunger, Wright recalled how enthralled he was by the Soviets’ campaign to restore the customs and cultures of Russia’s “lost and beaten peoples.” He was awed by the work of the linguists who reduced the “stammering dialects” of these peoples to written languages. “The first total emotional commitment of my life,” Wright said, came when he read how these experts had given “tongueless” nations of herdsman and peasants a written culture. As a young, unpublished writer who sought to speak for his own “forgotten folk,” he found inspiration in the Soviets’ attempt to revive the customs and cultures of peoples as scorned and despised as his own.

In her penetrating biography of Wright, Hazel Rowley tracks his passage through the tumultuous years of the Thirties and Forties. She follows the long arc of his career as a revolutionary writer — from his first encounter with Marxism in the dingy, paper-strewn rooms of Chicago’s John Reed Club, to his final break with Communism after years of chafing under party discipline.

It was the rising talents of the John Reed Club who exposed Wright to the forceful current of proletarian art. In their depiction of working-class life — the life of miners and millhands, teamsters and stevedores — Wright found a rough, vigorous realism: a style fashioned to capture “the culture from which I sprang” and “the terror from which I fled.” His angry verse was published in New Masses, whose radical editors were the first to recognize his genius. He was proud to call himself a “Negro Communist writer.” In his Chicago party cell, among men and women who abhorred prejudice, he realized that racial hatred could be conquered and saw that “the bane of my life” could, perhaps, be extinguished forever.

But Wright’s skepticism did not amuse party leaders. Before Native Son made him a celebrity, he was accused of certain errors and deviations. It was whispered that he was a “petit bourgeois degenerate,” and he was said to have “seraphim tendencies”: that is, to have withdrawn, as an artist, from the “struggle for life” and to have assumed the aspect of an “infallible angel.” His experiments in literary modernism were not welcome — (though his reading of Gertrude Stein’s Melanctha, a novel of two black lovers, was warmly applauded by an audience of black shipyard workers).

The party’s displays of intolerance galled him. He was appalled when a member of his chapter, denounced as an “enemy of the working class,” was made to confess his sins after an utterly farcical show-trial. Yet Wright remained in the party for nearly a decade. He made his departure in 1942, his disappointment aggravated by the party’s failure to challenge “Jim Crow” segregation in the new wartime army.

“After I broke with the party,” Wright told his friend Ralph Ellison, “I had nowhere else to go.” He found little comfort in French existentialism, whose doctrines he embraced after moving to Paris in 1947. He was by nature a fighter; and existentialism was no fighting creed. His repudiation of Marxism — “the starting point for a Negro writer,” he said — left him philosophically adrift.

But even in exile, Wright was conscious of the continuing struggle. He could not repudiate his desire “to tell, to march, to fight. . . to keep in our hearts a sense of the inexpressibly human.” It is fitting that he lies in Pere Lachaise cemetery, the last stronghold of the revolutionary Paris Commune.

Dean Ferguson is an editor of Transformation, a newly launched literary journal. He lives and works in San Francisco.

|

| Print