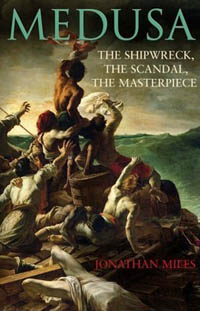

Jonathan Miles, Medusa: The Shipwreck, the Scandal, the Masterpiece, Jonathan Cape, 2007, pp. 288.

At midday on July 2, 1816, the frigate Medusa, flying the white flag of Bourbon France and bound from Rochefort to Senegal with a cargo of arms, ammunition, and other supplies for the soldiers and colonists it bore, ran aground on a sandy shoal fifty miles from the African coast. The shoal was well known to navigators and clearly marked on the captain’s charts; but the captain — an inept placeman named Chaumereys, who owed his appointment to noble blood and Royalist politics — had set the ship’s course straight for it, despite warnings from his veteran lieutenants. The Medusa, stuck fast to the sandbank, gave way to the violence of the breakers. Its hull crumpled, and Chaumereys gave the order to evacuate.

The lifeboats were too few, too small, and too decrepit to hold everyone on board; and Chaumereys and the colony’s governor took for themselves the most seaworthy craft. Room could not be found for many of the passengers and crew. The ship’s carpenters improvised a raft from masts, spars, and rough-hewn planks and hastily provisioned it with tubs of wine, sacks of biscuit, and barrels of flour. 146 men and one woman were herded aboard this makeshift craft, so crowded that those on its edges were forced to stand waist deep in water. Most of their provisions were jettisoned in a reckless attempt to accommodate them.

This rudderless raft was placed under the command of an injured midshipman. Among its passengers were Henri Savigny, the ship’s second surgeon, and a geographical engineer named Alexandre Correard, both men of radical views.

A tow rope was fixed to the governor’s barge, and the lifeboats — laboring under the weight of the inconvenient raft — rowed southward toward Senegal. Progress was infuriatingly slow, and Chaumareys’ second-in-command took it upon himself to relieve the barge of its burden. With a hatchet he severed the tow rope, the raft’s only lifeline. Chaumareys waved his hat; the loyal members of Governor Schmaltz’s entourage shouted “Long Live the King!”; and the lifeboats left the orphaned vessel behind.

This “half-submerged structure” was set adrift, to the oaths and imprecations of those aboard. It had no sails, oars, or anchors, and its only compass was lost by a maladroit workman. The wooden railing tacked to the edges of the raft was too low to protect its passengers. At nightfall the sea rose, and several men were swept away in the darkness.

On the second day the soldiers of the Africa Battalion — a unit composed largely of ex-convicts and mercenary adventurers, including, it seems, not a few Americans — mutinied and attacked the officers commanding the raft. Under Savigny’s leadership, the officers beat them back. The ensuing melee left sixty dead.

On the third day the famished survivors fell upon the bodies of the dead, and appeased their hunger with human flesh. They tore strips of skin and muscle from the corpses, and hung this meat to dry on the ropes that tethered the mast.

Windburnt, without water, their thirst palliated by an occasional mouthful of piss or salty wine, the castaways succumbed to exhaustion, sunstroke, murder, and suicide. Their wounds — many were hurt by the shifting timbers of the jerryrigged raft — were made agonizing by constant exposure to salt water. Some on the raft’s periphery were stung by medusae, or Portuguese men-of-war; all feared the marauding sharks.

On the twelfth day of their voyage, those who remained aboard the raft were astonished to see a vessel on the horizon. It was the brig Argus, dispatched to search the shoal for the lost Medusa. From despair and delirium the survivors passed into exultation; they raised one of their number — it may have been the black sailor, Jean Charles — to signal their distress with a hoop hung with handkerchiefs. The mirage disappeared, to the anguish of the survivors; amazingly, it reappeared within hours. The Argus turned about, hove to, and relieved the raft of a remnant of fifteen emaciated and stinking men. Of these fifteen, five died soon afterward.

Savigny survived the debacle, as did his companion, Correard. On their return to France in 1817, they combined to author an expose that swiftly became a surprising bestseller. They denounced the incompetence of the Royalist Chaumereys; condemned the perfidy of Governor Schmaltz, whom they accused of ordering the raft abandoned; and told a story of extraordinary pain and deprivation. No one could mistake the import of what they said. Their charges were a damning indictment of the ultra-right, whose party had put charlatans like Chaumereys and Schmaltz into power. Their narrative was read by Theodore Gericault — already, in his mid-twenties, a Salon prize-winning artist — who was to make its revelations the subject of the first masterpiece of French Romanticism.

In his Medusa: The Shipwreck, the Scandal, the Masterpiece, the English critic Jonathan Miles relies upon the same narrative of cowardice, endurance and survival to give pace to his own story of the Medusa disaster and its aftermath. Miles shows consummate skill in rendering the richly varied atmosphere of the African coast, from the sea-green obscurity of an Atlantic squall to the luminous heat of Senegal in midsummer. His portrait of Paris under the newly restored Bourbon regime is no less brilliant in evoking the atmosphere of a city weakened by avarice, corruption, and indifference.

In his Medusa: The Shipwreck, the Scandal, the Masterpiece, the English critic Jonathan Miles relies upon the same narrative of cowardice, endurance and survival to give pace to his own story of the Medusa disaster and its aftermath. Miles shows consummate skill in rendering the richly varied atmosphere of the African coast, from the sea-green obscurity of an Atlantic squall to the luminous heat of Senegal in midsummer. His portrait of Paris under the newly restored Bourbon regime is no less brilliant in evoking the atmosphere of a city weakened by avarice, corruption, and indifference.

Miles’ superbly drawn Gericault is a man possessed of remarkable gifts: a consummate horseman who brought a cavalryman’s dash to his painting; a draughtsman whose candidly erotic drawings revealed a mastery of chiaroscuro; and a painter whose vigorous style recalled the voluptuous line and color of Rubens. Against this array of talents Miles sets Gericault’s melancholia, which verged on madness in his final years.

Gericault, like many young artists of the Restoration, was a disciple of the Neoclassicist Jacques-Louis David, whose ideal of artistic perfection seems to have been the Parthenon frieze. David’s virtual dominance of French art had begun twenty years before, under Robespierre and the Jacobins, and had become well entrenched under Napoleon, whom David served as painter and propagandist. Gericault hoped to imitate the elegant symmetry of David’s paintings; but while David’s Roman heroes seem rigid or frozen — men not of common mold, but of Carrera marble — Gericault’s commoners are living men. They breathe, and they suffer; and their suffering is seldom relieved by any prospect of victory or redemption. Where David had painted Napoleon crossing the Alps, Gericault painted a wounded cuirassier leading his horse away from battle. Where David had painted the nouveaux riches at Napoleon’s coronation, Gericault painted the staring inmates of state asylums. Gericault sought to realize the grandeur, the monumentality of David’s style — in fact he was a fervent admirer of the master — but his temper was too violent, his nature too passionate, to rest easy with David’s Neoclassicism. There was in Gericault, as the Marxist critic Jack Lindsay has said, “a terrible and naked compassion.” David could sketch a haggard and slatternly Marie Antoinette as she drew near the guillotine, recording her anguish and exhaustion with deliberate coldness; it is hard to imagine Gericault doing the same.

The intensely ambitious Gericault hoped to measure his genius against David’s in a painting of monumental scope. The furor that followed the news of the Medusa disaster gave him his chance. In the spring of 1818, he set aside his studies for The Assassination of Fualdes — a painting, never completed, of a murder committed by Royalist thugs — to paint The Raft of the Medusa.

A work so large and ambitious demanded a studio of comparable size. Gericault found spacious lodgings on the Rue des Martyrs, in a working-class quarter of northwest Paris — a place inhabited largely by pensioners, invalids, amputees, and other ex-soldiers of Napoleon’s Grande Armee, the derelicts of the twenty years of war that ended with Waterloo. It was a district known for its radicalism, a matrix of revolutionary sentiment, the home to hundreds who exalted the memory of Robespierre and the Jacobin regime. Men like Savigny and Correard found a ready welcome there. So, too, did Gericault, whose contempt for Royalism may well have deepened to hatred in their company.

Gericault pursued his subject with the hardened passion of a forensic scientist. The research he devoted to the Medusa disaster was diligent and exacting. He interrogated Savigny and Correard, drawing out the details of their trauma; enlisted various artists and admirers, including the young painter Eugene Delacroix, to pose as victims and survivors; and crossed the English Channel to observe sea and sky at first hand. He commissioned the ship’s carpenter to build a small replica of the raft; visited hospitals and morgues to sketch the dead and the dying; and — in a gesture that may have presaged his descent into madness, and his death of tuberculosis at 32 — brought cadavers to his studio to sketch the effects of rigor mortis and putrefaction.

Gericault shaved his head and gave himself up to his work. He considered and rejected several episodes from the tragedy for his painting: the abandonment of the raft, to the shock and consternation of its passengers; the futile onslaught of the mutineers; and the final, ravenous embrace of cannibalism. Preparatory drawings of these events survive, and Gericault’s depiction of the mutineers’ rising, a combat of sabers and knives, is an arresting study of desperation and fury. At length he fixed upon the moment of seeming deliverance — the sighting of the brig Argus, sent to salvage the Medusa and rescue its survivors — as the most dramatic theme.

In eight months, Gericault produced a canvas of heroic proportions, which still retains its power to awe the viewer. Measuring 16 by 24 feet, The Raft of the Medusa is rendered in richly layered greens and browns, the colors of a storm in the Saharan latitudes. (These colors have darkened and grown brittle as the bitumen of Gericault’s paints has corrupted them; and the viewer who wishes to see Gericault’s masterpiece as he wished it to be seen is well advised, says Miles, to study the excellently-preserved copy hanging in the Museum of Picardie, in Amiens, rather than the decayed original on display in the Louvre.)

The composition is pyramidal; the broad base of the raft narrows to an apex in the figure of the shirtless sailor waving to the Argus. But a pyramidal comparison does nothing to convey the movement that Gericault captured on canvas. The raft slides into the shallow trough of an oncoming wave; the strongest of the survivors rush forward to signal the Argus; in an imperative gesture, Correard turns to Savigny, thrusting his arm outward to mark the brig’s position. The weaker passengers try to rise to their feet. Nearby, oblivious to the coming rescue, a man sits in silent resignation, holding the body of his son. In a moment, the Argus will slip away and move on, a chimera.

Despite his newly won knowledge of debility and death, Gericault depicted the raft’s passengers as strong and well-muscled, near Apollonian in their beauty. In this he was following the example of Michelangelo, whose Sistine frescos he had seen and admired during a recent sojourn in Rome. He had studied these frescos with great care. Even the damned of Michelangelo’s Last Judgment, he knew, were men of heroic build, men still possessed of beauty despite their condemnation. Gericault gave to his castaways a similar dignity. They were not hideous. Like Michelangelo’s damned, their beauty invested their sufferings with a measure of tragedy.

The Raft of the Medusa marked a revolutionary departure in French painting. Traditional paintings of historical scenes had exalted the deeds of emperors, kings, and noblemen. But Gericault made the fate of common men — a surgeon, an engineer, a carpenter, a sailor — the theme of his immense tableau. There were no great men in his canvas. There was no emperor to console the wounded, as there was in Gros’s Napoleon at Eylau; there was no emperor to heal the sick, as there was in Gros’s Napoleon at Jaffa. There were no kings, noblemen, generals, or heroes. There were only victims; and they were dead, wounded, or delirious with an apparently illusory hope.

The most subversive element of the painting was the placement of a black man — the sailor signaling the Argus with a rag of red and white — in a dominant position among the men aboard the raft. As Miles observes: “To place a figure who, because of his color, was generally considered to be sub-human at the summit of whatever hope The Raft of the Medusa may be said to express, was daringly, dangerously avant-garde.”

The Raft of the Medusa sparked a furious controversy at the Salon, where it drew large crowds in the summer of 1819. Ironically, it won praise from the King, who told Gericault that his “Shipwreck” was surely no shipwreck for his career. But the Louvre passed it over for acquisition, and Gericault was paid off with a gold medal (one of 32 awarded to Salon invitees) and a commission for a Sacred Heart. The latter prize — which must have struck Gericault as an insult — he disdainfully passed on to an admiring Delacroix. His unwieldy canvas was packed up and shipped to London, where it was a thoroughgoing success. And no wonder: English museum goers gloated over its arraignment of French stupidity and incompetence.

Under Correard’s influence, Gericault set his hand to a new endeavor: a tableau to be called The Treatment of the Blacks. Correard had seen evidence of the flourishing slave trade in Senegal, and Gericault was moved by his description of its horrors. This trade — carried on with the connivance of Governor Schmaltz, who was entrusted by the government with its suppression — outraged liberal opinion in France, and fostered a movement for its total abolition. Sleek-hulled slavers could often be seen in the harbor of Senegal’s capital, where Schmaltz openly profited from what one priest called an “execrable commerce in human flesh.” Gericault answered Correard’s appeal with plans for another massive canvas, which he conceived as a manifesto against French complicity in the slave trade. But he was sickened by recurring depression and advancing tuberculosis; and his great manifesto was never painted. Like several other projects — The Assassination of Fualdes, The Opening of the Doors of the Inquisition, and several pieces inspired by the Greek War of Independence — it was left incomplete.

Gericault realized that his name and reputation were inseparable from The Raft of the Medusa, which was to be his only masterpiece. Its notoriety did nothing to satisfy his ambition. Lying on his deathbed, he is said to have rendered a withering opinion of its merits: “Bah! Une vignette!”

Gericault fooled no one. His “vignette” inspired artists, radicals and reformers for decades after its debut in 1819. They saw in it a potent metaphor for oppression, betrayal, and abandonment. As late as 1968, the Hamburg premiere of The Raft of the Medusa — a “red” oratorio composed by Hans Werner Henze — triggered police intervention and court action. Conservatives decried the appearance of red flags on stage, and denounced the performance as a left-wing demonstration. In the 1990s, a play of the same name by the American playwright Joe Pintauro stirred gay activists in the fight against AIDS.

The Raft endures; Gericault’s message still resonates. One need only remember the survivors of Hurricane Katrina, hailing police boats and helicopters from their rooftops. Or, more recently, the boatload of African refugees who survived a sinking in the Mediterranean by clinging to a Maltese trawler’s fishing nets. Or, now and again, the Cubans, Haitians, and Dominicans found drifting off Florida in rafts crafted of stolen planks and discarded tires.

The Raft of the Medusa is no vignette. Life imitates art, and in life the Medusa tragedy endlessly repeats itself. The Raft is a tableau vivant: a living picture whose figures, drawn from contemporary events, re-enact the tragedy of the Medusa’s castaways. Like Savigny, Correard, the carpenter Lavillette, and the sailor Jean Charles, they are waiting for the Argus.

Dean Ferguson is an editor of Transformation, a newly launched literary journal. He lives and works in San Francisco.

|

| Print