When the Russian Revolution of October 1917 took place, it raised the hopes of the working class worldwide that a socialist state was possible. The civil war that followed plus the intervention of foreign powers devastated the economy, necessitating a postponement in the transition to socialist relations of production. The New Economic Policy was a stop-gap measure to sustain agricultural and industrial production in the face of war and potential famine. It was not until the 1930s that collectivization of farms and factories, and state ownership of the means of production, could be completed. The violence before and after October 1917 was taken as an indication that a peaceful transition to socialism was not possible because the propertied classes would not willingly give up their privileges.

On the contrary, when Boris Yeltsin effectively dissolved the Soviet Union in December 1991, allowing the republics to go their own ways, and vowed to transform Russia into a capitalist market economy, it surprised many that the counter-revolution could have happened with so little effort and largely without violent upheaval. Many on the left lamented the apparent collapse of socialism in Russia and withering away of socialist relations of production in the republics.

The 1917 capture of state power by the Bolsheviks was accompanied by workers winning control of factories and establishing workers’ soviets. However, a careful examination of Soviet history suggests that the period from the end of the New Economic Policy (1929) to the beginning of the Great Patriotic War (1941) witnessed two seemingly contradictory trends. First, the consolidation of collective and state ownership of the means of production throughout the economy prompted Joseph Stalin to declare that socialism had been achieved and that classes had been abolished. Second, Stalin’s purges of the Bolshevik Party and dismantling of the soviets effectively overthrew workers’ power and established the rule of the bureaucracy.

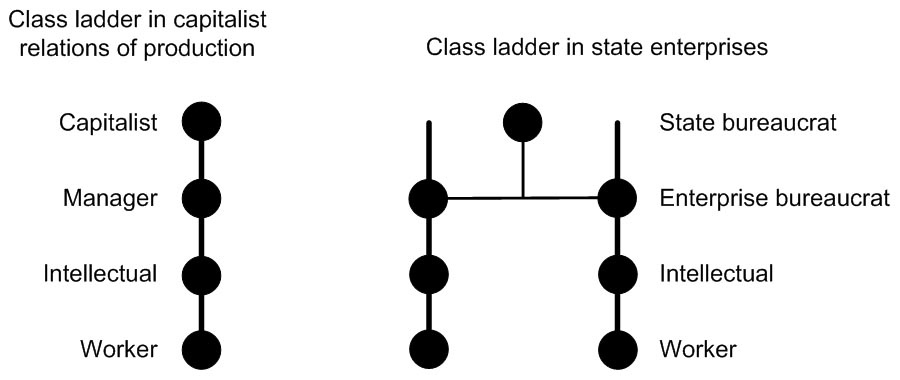

The bureaucracy’s continued ideological adherence to the state playing a central role in the egalitarian redistribution of wealth provided a veil of “socialism” that led many on the left to consider the Soviet Union to be some sort of “socialist,” “revisionist,” or “deformed workers’ state.” The prevalent failure to recognize the bureaucracy as a ruling class derives, in part, from the bureaucracy being divorced from a polar position in the relations of production, e.g., it neither owns capital per se nor necessarily appropriates surplus for its own benefit. Nevertheless, state enterprises are under the direct control of managerial elites who appropriate surplus for reinvestment or for the state. They are the apex class in a “decapitated” relation of production that excludes an owner class, but includes a class ladder of managers, intellectuals (sellers of knowledge power), and workers (sellers of labor power). If enterprise bureaucrats clearly represent a class because of their position in a relation of production, so are state bureaucrats, by extension, members of that bureaucratic class owing to their authority over enterprise bureaucrats and power to appropriate enterprise surpluses to operate the state apparatus.

Thus, workers and intellectuals alike were alienated from state capital and its appropriation. By the 1960s, this was clearly evidenced by widespread attempts to circumvent the system, including the black market and the underground economy. Without specifying which class truly held state power, the national slogan of the day was “Служите государство!” (“Serve the State!”) It certainly was not of the working class.

As the first president of post-Soviet Russia, Boris Yeltsin unleashed a wave of privatizations that sold gigantic state enterprises for a song, catapulting a handful of well-connected buyers into becoming the new capitalist oligarchs. Though once a top CPSU leader, Yeltsin, the bureaucrat, had no inherent class interest in capitalist versus state capitalist versus statist versus socialist relations of production. For Yeltsin, selling off state enterprises was a means of dissolving the power base of his opponents in the bureaucracy and consolidating his own power within that bureaucracy.

By the same token, Vladimir Putin has no inherent class interest in preserving private enterprises. His efforts in recent years to re-establish state control over key sectors of the economy — oil (Rosneft), natural gas (Gazprom), oil and petrochemical transport (Transneft and Transnefteprodukt), automobiles (Autovaz), metals (VSMPO-Avisma), aviation (United Aircraft Corporation), and shipbuilding — served to dissolve the power base of free-market oligarchs who were challenging the power of the bureaucracy.

The zig-zags between market capitalism, state capitalism, and statism are not a consequence of one class overthrowing another each time, but rather of the bureaucracy itself vacillating on the relations of production. Yeltsin’s privatizations and Putin’s reassertion of state ownership of key means of production are neither counter-revolution nor revolution, but manifestations of the bureaucracy vacillating in its game of consolidating political power and neutralizing opposition.

Despite its defects and contradictions, the Soviet state for 45 years provided an effective counterbalance to global imperialist hegemony, preventing the outbreak of major wars of unprovoked aggression by the U.S. government. But with the Soviet Union already weary of the war in Afghanistan and facing political turmoil at home, it was in no position to deter the first U.S. invasion of Iraq in January 1991. Since then, Russia has acceded to U.S. superpower hegemony, yet has continued to oppose U.S. aggression, extraterritoriality, exceptionalism, and blatant violations of international law. As a bureaucratic state (as opposed to the U.S. capitalist state), Russia’s worldview will continue to differ from that of the U.S. and the European Union in seeking accommodation rather than confrontation with developing countries and anti-imperialist movements.

For the left, the problem is not one of a “failure of socialism,” but rather of a failure in the first place to continue the revolution to consolidate the socialist state and socialist democracy in the former Soviet Union. One lesson of the Russian Revolution for the project for twenty-first century socialism is that both state power and the relations of production must come fully under workers’ democratic control. While the Russian experiment in socialism may have floundered in the twentieth century, socialism itself did not fail. The movement for twenty-first century socialism has an historic opportunity and mandate to correct these mistakes and make true socialism possible.

Sharat G. Lin writes on global political economy, the Middle East, India, labor migration, public health, and the environment. This essay is a summary of a talk presented at a public forum marking the 90th anniversary of the Russian Revolution held in the Humanist Hall, Oakland, California on October 13, 2007. The date generally accepted as marking the Bolshevik Revolution is November 7, 1917 (Gregorian calendar), even though it is frequently referred to as the “October Revolution” of October 25, 1917 (Julian calendar).

|

| Print